Estate Jewelry: Liz’s Diamonds and Victorian Brooch Jokes

OK, so I’m sure you guys have heard about the big Elizabeth Taylor jewelry auction, right? The pieces are going on exhibit in Los Angeles on October 13–16, but tickets have already sold out. After that they’ll make appearances in Dubai, Geneva, Paris, and Hong Kong, before finally landing in New York for an exhibit at Christie’s from December 3–12. The serious jewels (80 in total) will then go up for auction in an evening sale on December 13. Other auctions will follow, including lesser jewels, clothing, memorabilia, and paintings.

This ring was the first piece of jewelry Richard Burton ever bought for Elizabeth Taylor. Now renamed the “Elizabeth Taylor Diamond,” it was originally known as the Krupp Diamond. It’s a 33.19 carat, D-color, potentially internally flawless Type IIa rectangular-cut diamond, and it carries an estimate of $2.5 to $3.5 million. Taylor owned larger diamonds, but she loved this ring, and wore it just about every day.

Another standout auction piece is “La Peregrina,” the famous 16th century pearl that was originally part of the crown jewels of Spain, and passed through multiple regal hands until Burton bought it at auction in 1969 for a mere $37,000. (At that point it was set as a pendant with a somewhat simple long pearl chain, but later, after Taylor literally had to pry the pearl from the jaws of one of her dogs [!!!], she had the piece set more securely in an ornate Cartier necklace, the design of which was based on a portrait Taylor had seen of Mary Queen of Scots.) It’s estimated at $2 to $3 million.

Also included in the sale are jewelry suites by Bulgari and Cartier, a ruby and diamond ring by Van Cleef & Arpels, and a diamond tiara given to her by former husband Mike Todd.

Among other jewelry, the Krupp, La Peregrina (with its original chain), and the Mike Todd tiara in this photo of Taylor from the 1969 movie premiere of Burton’s film Staircase will all be on display. She will forever be the only woman ballsy enough, and beautiful enough, to pull off a look like this.

Circa 1890, this is a gorgeous floral tiara, with old brilliant and rose-cut diamonds adorning the branches and leaves, and pear-shaped pearls forming the buds. It’s gold, and also has a detachable setting that can convert the piece to a brooch.

This mid-19th-century gold-filled bracelet features two coral and 14k clasps, and is actually made up of two smaller bracelets. The Victorians loved jewelry, and even their babies didn’t escape adornment. The two original bracelets in this piece would have been placed on the wrists of a baby, and the use of coral was a nod to superstition, as it was believed for centuries that coral provides protection from the evil eye. (And actually, lots of Italian jewelers still sell coral horn pendants today, for exactly this reason.) Once the child had grown, the two bracelets were joined together as a single piece of jewelry. Ingenious!

I love this finely engraved 14k Edwardian headband; it reminds me of Helen Mirren in Caligula. (Minus all the nudity.)

Nobody can ever tell me that the Victorians didn’t have a sense of humor (seriously, they rested saucers on their cleavage).

This is a fantastic micromosaic, circa 1850, depicting a smiling bunny driving a biga (or two-horsed chariot) led by two peacocks. THERE IS NOTHING NOT TO LIKE ABOUT THIS. The gold setting is a later, contemporary addition.

According to the dealer, this Georgian ring is believed to have originated with Caroline of Ansbach, who married George II in 1705, became Princess of Wales in 1714, and was Queen Consort of England from 1727 to 1737.

Circa 1720, it features the cypher “C,” topped with Prince of Wales feathers and floral motifs at the sides, all in silver on gold with diamonds. The band is engraved “Vivat de Princesse,” or “Long Life to the Princess.”

Circa 1930, this signed Van Cleef & Arpels Art Deco lipstick case is 18k gold with gold, turquoise, and black-and-red enameling. It makes me wish I wore lipstick; although I suppose it could also double as a place to hide your mad money (or a joint, but of course none of us would ever do such a thing).

A masterpiece of delicacy, this cuff bracelet incorporates 11 carats of micro-pavé and bezel-set diamonds into an open-work design of 18k white gold interlaced circles, with two invisible catches.

This ridiculously cute (and also strikingly modern-looking) late-19th-century French bangle bracelet is 18k gold, with black polka-dot enameling and five pearls.

This beautiful little bottle (it’s only 6.5 cm), is set with foiled rubies and emeralds, and dates to the 17th century. It comes from Mysore, South India, and was used to store kohl. Again, my makeup storage implements are looking pretty pathetic today.

Circa 1900, this very affordable ring features 18k yellow and white gold with red strass (a type of paste) “rubies,” and stone pearls. (Stone pearls were sometimes used in the 19th century instead of natural pearls, because it was much easier to match their size and color.) So, even though the rubies aren’t real, it’s still an 18k ring, and in perfect shape because it comes from stock that had been locked away in a vault for decades.

Usually, when someone mentions Native American jewelry, most people think of the silver and turquoise pieces indigenous to the Southwestern United States. But there’s a lesser-known form of Native American jewelry that originated in the east, and it has a fascinating history that’s closely tied to Canada, Europe, and the U.K.

European traders first began arriving in North America in the 1500s. They were desperate for fur, which was being used extensively in clothing back home — particularly in the manufacture of top hats, which were made from black beaver pelts. The Europeans settled in the spots along the east coast that were most conducive to animal trapping, so New York’s Hudson River Valley, New England, the Great Lakes, and areas extending up into Canada were popular. Many of these early traders were French, but Dutch, English, and other Europeans also made their way to North America.

The foreigners soon became acquainted with the tribes of Native Americans that were living along the eastern coast (including the Delaware, Algonquin, and Ottawa, as well as the Iroquois Nation), and commerce quickly sprang up between the two cultures. In return for pelts, the Europeans offered the Native Americans cloth, knives, needles, and other practical items. The most popular items, however, were ornamental pieces — usually jewelry — that became known as “trade silver.” Prior to this, the Native Americans had worn jewelry made from copper, shell and bone, and the Mohawks actually ran a successful native trade in lead and pewter ornaments. But the brooches, crosses, and other ornaments found in trade silver became especially popular with the Native Americans, and they used them as embellishments for their dress.

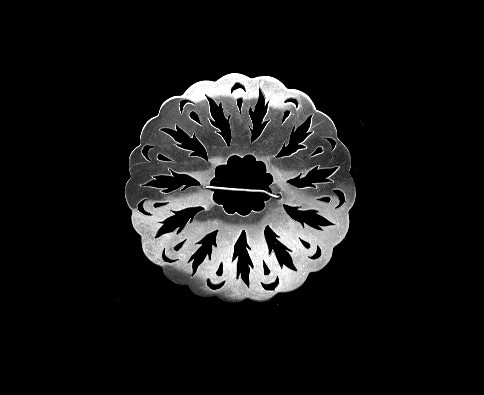

Early trade silver designs were simple. Rings, round and heart-shaped brooches (similar to the reproduction piece above), beaver pendants, and Masonic pins were common, and some pieces also showed a French Jesuit influence, with cross designs and religious symbols. “Earbobs” (dangle earrings consisting of a hoop supporting a dangling ball and cone) also were popular, as were “Luckenbooth” brooches. The design (which represents friendship or betrothal), features overlapping hearts topped with a crown, and is believed to have originated in Scotland. It’s similar to the Irish claddagh, which was another design passed on to the Native Americans by the Europeans.

As the European silversmiths became established in the New World, they created workshops, and Native American artisans worked with them. The pairing of the two sensibilities soon created a boom in both the quantity and the quality of the items produced. The Europeans provided advanced molds that helped facilitate greater production, while the Native Americans brought their iconography to the table. The variety of designs they produced was enormous: Images from nature and mythology began to appear, as well as symbols of friendship and loyalty. Variations on the heart-topped-with-crown designs were popular, and often the crown was replaced with other symbols, such as the tail of a bird, a face, or an owl (all of which can be interpreted as guardians of the heart).

Trade silver saw its greatest popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Pieces often were fashioned from Spanish silver coins, but the term “trade silver” is actually misleading. Pieces needed only a bright polish and decorative or barter usage to be called trade silver, and they were made of a variety of metals, including pewter and brass. In the late 1800s, an alloy of nickel, copper, and zinc known as “German” or “nickel” silver was commonly used. Actual silver items were, of course, the most desirable (and most expensive).

Information on the barter value of individual pieces is hard to find, but 19th-century records cite some trading values for Albany, N.Y. There, large silver armbands were the trade equivalent of four large beavers or bucks, while silver brooches were worth one raccoon each, and large crosses were valued at one small beaver or medium buck. Earbobs were worth one doe.

Eventually, the 1800s saw the human population grow and the beaver population decline on the east coast. Trade began to move west toward the end of the century, and the use of trade silver declined.

Today, the whereabouts of much of this silver is unknown. Some pieces are in museums and private collections, and others surface in the hands of dealers — more about that later! — but it’s also possible that a lot of it is buried. Native Americans often wore hundreds of trade silver pieces on their clothing as a display of prestige or wealth, and that jewelry was also affixed to their burial garments and buried with them.

Right now there’s a popular demand for trade silver among historical reenactors, and many companies make reproductions for this market. It is, however, very easy to fake an old patina on a contemporary piece (created from an old coin) and sell it as antique, and unfortunately there’s a LOT of that going on today — particularly on the internet. If you want to buy a piece of trade silver, do as much homework as you can, and make sure the piece is coming from an extremely reputable dealer. But even still, it’s a crapshoot.

(Note: Sources consulted for this entry include W.H. Carter’s North American Indian Trade Silver, Hothem House, 1996, and N. Jaye Fredrickson’s The Covenant Chain: Indian Ceremonial and Trade Silver, National Museums of Canada, 1980.)

Previously: Tiger Claws, Secret Hearts, and Opal Madness.

Monica McLaughlin apologizes for going on so long about trade silver, but she thinks it’s a really neat subject and she hopes you do, too.