Watching Alyssa Milano Grow Up

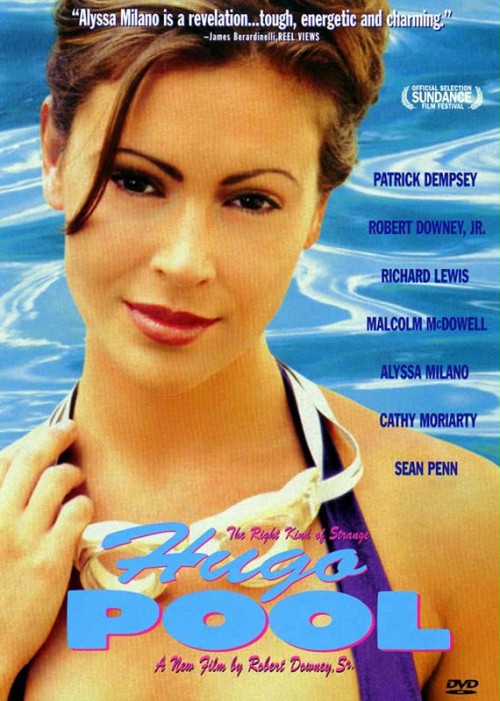

In one of the earliest scenes in 1997’s Hugo Pool, the “prettiest pool person in the Canyon” gives herself a shot of insulin. It’s part of a morning-routine montage—wake up, shower, dress—and this is the penultimate moment. She sits down, throws her leg onto the counter and the camera dwells on her clear beautiful face as she plunges the needle into her thigh with a quick wince. Then, as she slowly empties the contents of the vial into her body, in an instant, a puerile expression flashes over her face—eyes flick up, lips pout. “Oh, well,” the look says. But it’s only a moment. She allows herself one second of self-pitying indulgence before moving on. She is an adult now, and these are the things adults must do.

Hugo Pool premiered 20 years ago. It was the last feature film by Robert Downey Sr. (Junior has a small role as an arsonist filmmaker with a weird accent), a sort of love letter to his second wife, who co-wrote it before she died of ALS (Lou Gherig’s disease). The film was a flop—$13,000 at the box office, an F in Entertainment Weekly—the definition of middle-of-the-road ’90s quirk. It revolved around a young woman named Hugo Dugay who is forced to look after an array of dysfunctional Angelenos—including her parents—as she goes about her work day. Along the way, she meets a man with ALS, with whom she falls in love.

The role of Hugo was written for a man, but Alyssa Milano was the only woman for it. The “Who’s the Boss?” child star, who had just completed a string of soft-core thrillers, was the ideal person to play a tattooed virgin, who neither drinks nor does drugs, and who parents her parents. Hugo oscillates between innocence and maturity just like Milano herself at age 24, a kid trying so hard to be an adult.

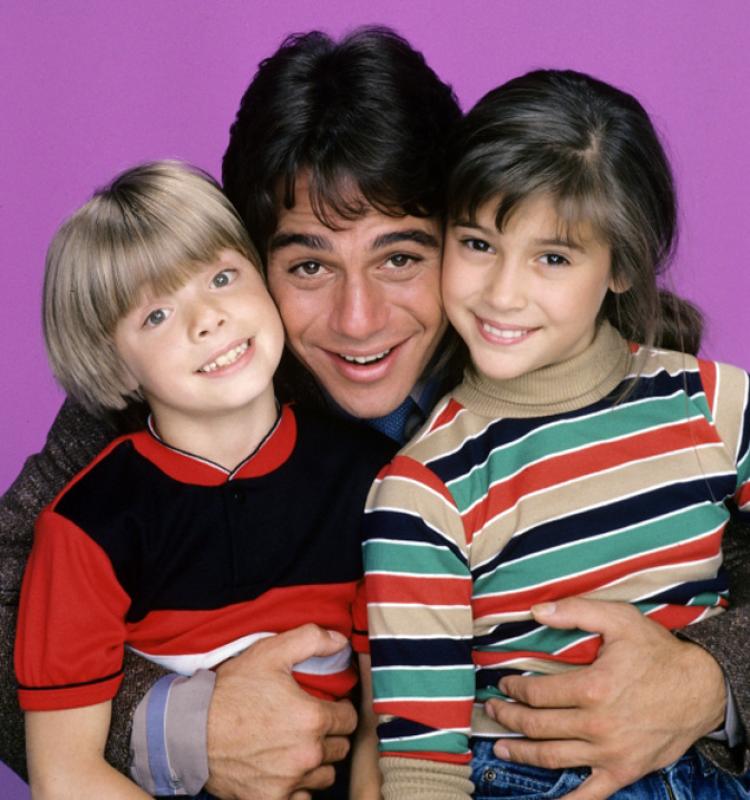

“Who’s the Boss?” defined Milano’s career. She played Samantha Micelli—the daughter of a male housekeeper (Tony Danza) working for a rich female advertising exec (Judith Light)—for eight years, from pre-pubescence to online rumors she was having an affair with her onscreen dad. Despite the show’s overtures towards second-wave feminism, Milano’s trajectory was stereotypically gendered. In the first season, reflecting her own experience as an 11-year-old girl, an entire episode was devoted to Samantha’s first bra, exposing Milano’s own private life to public discourse. “I’d walk down the street and get recognized,” she told Entertainment Weekly. “People would be like, ‘That bra episode! You’re getting older, you’re growing up!’ It was so mortifying.” People magazine later described her as “pert” and treated her on-screen flirtation with co-star Scott Grimes like an Old Hollywood affair. “I think kids can relate to an innocent romance instead of the jumping-into-bed romances they see on ‘Dynasty’,” Milano said. She was in eighth grade.

By 16, Milano was a bona fide teen idol who had appeared in various states of big hair, big makeup and multi-colored shapeless garments and earrings in magazines like Tiger Beat, Bop and Teen Beat. She had a pop music career in Japan, a weekly advice column in Teen Machine and a questionable Jane Fonda-style workout video called Teen Steam in which she wore a sports bra and lycra shorts and engaged in squats, splits and other bends (Milano later found out that one website affixed her Teen Steam head to a child’s naked body). Both Justin Timberlake and Channing Tatum would later admit she was their number one crush. Other men were less coy. “To be dating somebody and then hear him say, ‘I have a poster of you in my bedroom’ or ‘I always fantasized about you’ is a weird thing,” Milano told Stuff magazine in 1999. But certain men seemed convinced her public persona superseded any boundaries she might have. “I’ve had guys—famous guys—come over to me and be like, ‘I used to masturbate to you when you were on that show,’” Milano said in FHM.

In 1991, the year before she left “Who’s the Boss?”, Milano played a teen prostitute in an indie film called Where the Day Takes You. Her tough-talking midriff-bearing jean-shorted “slut” would be notably egregious if it weren’t for a parade of other popular child stars—Balthazar Getty, Lara Flynn Boyle, David Arquette—trying to pass for runaways. The film is best known, if at all, as Will Smith’s big-screen debut as a wheelchair-bound street kid. “People are going to see me as a prostitute and say, ‘That’s the girl from ‘Who’s the Boss?’” Milano told the Los Angeles Times. “The important thing for them is to have an open mind.” She admitted in the same interview that she had auditioned for every role in her demographic, the implication being that she was taking what she could get.

The lack of options in the ’90s for young women in Hollywood, particularly ex-child stars, was exemplified by the Amy Fisher clusterfuck. Three TV movies arrived almost simultaneously, all of them fictional accounts of the 16-year-old Long Island girl who shot the wife of the 38-year-old man who had sexually exploited her. The first, Lethal Lolita, starring Noelle Parker, aired in December 1992 on NBC. A month later, Drew Barrymore starred in ABC’s The Amy Fisher Story, which premiered on the same night as Milano’s CBS version, Casualties of Love: The Long Island Lolita Story, but performed better. This would be the theme for the next four years: Milano overshadowed by the younger blonde’s big screen pedigree and even bigger personality.

Poison Ivy came first in 1992, with Barrymore, in her mid-teens, playing an actual naughty school girl. That same year she posed nude for the cover of Interview magazine with her very ’90s boyfriend Jamie Walters, best known for his role in Fox’s The Heights, about a suburban rock band, for which he also breathed the chart-topping theme tune (“How Do You Talk to an Angel?). Milano followed suit, going topless on a beach for Bikini Magazine and starring in Poison Ivy II. Then, in 1995, Barrymore hit the apex of her exhibitionism, popping up in lavender lace panties on the cover of Playboy and flashing David Letterman on live TV. By this point Milano was quietly languishing in the softcore B-movie Embrace of the Vampire, which played off her child stardom, advertising her “first revealing role,” and led to a lawsuit when a website lifted nude stills. “The outcome is that I have an amazing nudity clause in my contract, and I now have full control over all my nude scenes,” she told The New York Daily News. It was a minor victory in an industry that insists on sexualizing its female stars from the first (Milano would headline another erotic thriller that year, Deadly Sins, before appearing as Reese Witherspoon’s promiscuous BFF in Fear). “After [“Who’s the Boss?”] was over, I was trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life,” Milano explained to Esquire. “I wanted to continue working, but I was only offered parts as the hot, steamy, sexy girl. So I took them.”

Cameron Diaz was initially cast as the girl who visits eccentric Laurel Canyon pool owners throughout the day while baby-sitting her parents and Patrick Dempsey (as a wheelchair-bound McDreamy). But then she was hired to play the perfect woman in My Best Friend’s Wedding and Milano stepped in. Hugo Dugay looks young—she could still be a teenager, and yet she owns a pool business. She appears to also own a house, or at least dwell solo in a reasonably sized abode. She dutifully administers her insulin, packs her bag with a wad of cash and fruits, and scrapes her father off the floor. She is the self-appointed adult, floating her mom’s gambling addiction, trusting her father to work despite his inability to even stay awake, satisfying her customers. She is reminiscent of a poised 13-year-old Milano in that People interview about her non-existent love life.

Hugo’s beauty is something she wears like an accident of nature. She absentmindedly knots her hair atop her head, wears no makeup, sports old hoodies, tank tops. She even tries to pop a zit that doesn’t exist. Despite the camera lingering on her legs as she sleeps, watching her shower, taking in her short-shorted behind as she leans into her truck, there is something asexual, almost infantile about her. She dispassionately confronts her heroin-addicted dad, but later breaks down. Her walk is artless and bouncy like a kid’s, her voice childlike. These appear to be the remnants of a phantom childhood she was not in fact provided. Her tattoos are a rare milestone: “Because I’m afraid to have sex and I don’t do drugs—what else is there?”

Hugo’s beauty is something she wears like an accident of nature. She absentmindedly knots her hair atop her head, wears no makeup, sports old hoodies, tank tops. She even tries to pop a zit that doesn’t exist. Despite the camera lingering on her legs as she sleeps, watching her shower, taking in her short-shorted behind as she leans into her truck, there is something asexual, almost infantile about her. She dispassionately confronts her heroin-addicted dad, but later breaks down. Her walk is artless and bouncy like a kid’s, her voice childlike. These appear to be the remnants of a phantom childhood she was not in fact provided. Her tattoos are a rare milestone: “Because I’m afraid to have sex and I don’t do drugs—what else is there?”

This bubble of naivete seems to encase her even at the worst times. An harmless old man suddenly asks to look down her pants and, with a look of momentary disgust but not shock, she staccatos, “I. Think. Not.” (Another, “Oh well” look). While Hugo and her mother clean his pool, a man vulgarly discusses the women with his son, but neither of them hear it. And when she is tasked with helping Dempsey urinate, Milano is shot from above accentuating her diminutiveness as she reaches into his pants (while shielding her eyes, further evoking a kind of immaturity) while he towers above her from the truck bed. Even Dempsey’s fantasies are chaste—Hugo in a lace dress, Hugo on a swing, Hugo holding his hand. Immobilized, he is the perfect man. Hugo is not afraid of him because she is in control. She puts her hand on his thigh, she reclines his bed, she kisses him, removes her shirt, takes her hair down. But when he unexpectedly dies, she shifts her eyes away and snaps them back in case he might be joking. Seeing that he is not, she cries. In her final scene she drives with a steely expression on her beautiful face. She looks older. From lack of control to agency, innocence to maturity.

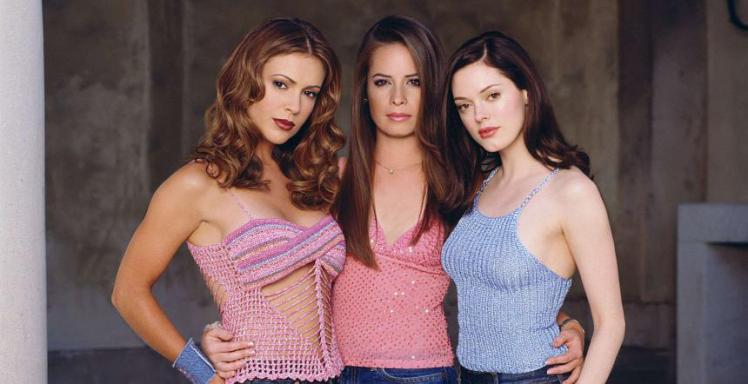

In The New York Times, Stephen Holden wrote that Milano was “clear and understated” and that she gave “the film its heart.” What he did not mention was that the life of the 24-year-old former child star, as with so many great performances, is threaded through the fiction. Her own flirtation with adulthood imbues the screen as she swings between playful sweetness and set-jawed practicality. “As a child star, to be able to not only make the crossover but to be recognized as an influential talent in the indie film industry really turned my life around,” Milano reportedly told FHM in 2002. “Melrose Place” producer Aaron Spelling saw “Hugo Pool” and hired her for the show (as Michael Mancini’s younger sister) then went on to cast her in “Charmed,” which would secure her career as an adult actress.

The impish appeal that Milano forged out of “Hugo Pool” continues to define her. It has powered network series like “Romantically Challenged” and “Mistresses” and even, more recently, bubbled up in the margins of “Wet hot American Summer: Ten Years Later.” Her past buoys her present, which is why her voice in the chorus of #metoo’s was so powerful – because her coming of age was also ours alongside it. Milano had always claimed that, despite her laborious upbringing in Hollywood, she was not sexually exploited. “I was so lucky, I mean, I have no casting couch stories or weird sexual-harassment issues,” she said in 2001.

Sixteen years later, in the aftermath of the Harvey Weinstein allegations, she adopted the #metoo hashtag, which had women acknowledging their own experience with abuse (Milano is profiled as one of the Silence Breakers in TIME’s Person of the Year issue). “I’m not ready to go into specifics about my own experiences with abuse,” she wrote on her website, “but I can say that I have been assaulted and sexually harassed more times than I can really recall off the top of my head.” Milano’s voice came late due to a conflict of interest—she is friends with Weinstein’s wife, Georgina Chapman (she is also married to Dave Bugliari, an agent at CAA, which the Times included in the Weinstein “complicity machine”—CAA has since apologized).

The vacillation recalls her ambivalence in “Hugo Pool,” a film which, for all its faults, elegantly established the lingering uncertainty of adulthood. When Milano publicly supported Chapman on “Megyn Kelly Today”—“Georgina is doing very well,” she said. She had to face her “Charmed” co-star, Rose McGowan, who had accused Weinstein of rape, and tweeted in response, “You make me want to vomit.” In reply, the 45-year-old mother of two, ever poised, shelved her characteristic equivocation and in one sentence announced her firmly established maturity: “I stand by every woman in the pursuit of permanent change and gender equality.”