A Timeless Portrayal Of Misogynistic Violence

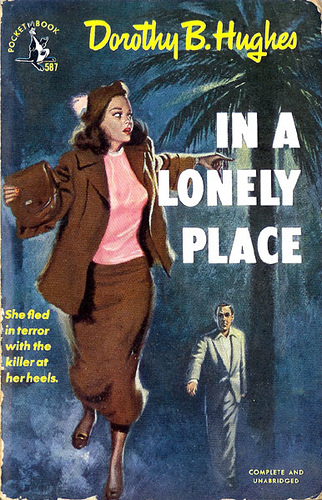

Seventy years ago, a novel was published that takes place in a world of drive-ins, dames and drinks bars at home, but analyzes male violence in a way that could come from a despairing Twitter thread today. That novel, In a Lonely Place, was written by Dorothy B. Hughes, a great pulp fiction writer whose gripping tales of gangsters, spies or murderers hide keen examinations of the question of human evil. (For a full run-down of Hughes’ life and work, read this brilliant essay by Sarah Weinman).

The novel takes place in Los Angeles and follows Dix Steele, a former war pilot who claims he’s moved to the city to work on a book. But he spends much of his time wandering the streets at night. Sometimes, young women catch his eye, and he follows them. Meanwhile, fear spreads around the city as a mystery killer rapes and strangles a series of victims. When Dix discovers that his old air force buddy, Brub Nicolai, is now the police detective investigating the case, he’s fascinated. Dix is living in a luxurious apartment belonging to another old friend, Mel Terriss, and claims he’s subletting it while Mel’s living in Rio. Except no one’s heard from Mel in months, and Dix is now wearing his jacket and driving his car. Dix is also strangely reluctant to talk about Brucie, a young English woman he and Brub knew during the war.

The tension of In a Lonely Place doesn’t come from solving the mystery of the murders. We know it was Dix. Hughes never explicitly states it, but she wrings plenty of tension and black comedy out of the familiar cat-and-mouse dynamic of the killer following his own investigation. As Dix spends more time with Brub and his senior officer, Lochner, almost every conversation they have is layered with irony. At one point, Nicolai offers to show Dix the latest crime scene; Dix gives him and Lochner a lift to the site, and Lochner says, “The only place we’ll find anything is in his car”.

What makes the novel such a taut thriller is how closely we follow Dix’s efforts to escape arrest. The novel is told in a free indirect style: the third person, but from Dix’s point of view—the language echoing his thoughts. It has an unsettling effect, placing the reader in the mind of a murderer, but allowing us to see the truth he constantly shies away from.

It’s especially frightening because Hughes pulls no punches in her depiction of Dix’s misogyny. Here’s how she introduces him, spotting a girl on the dark and foggy streets of Beverley:

He didn’t follow her at once. Actually he didn’t intend to follow her. It was entirely without volition that he found himself moving down the slant, winding walk. He didn’t walk hard, as she did, nor did he walk fast. Yet she heard him coming behind her. He knew she heard him for her heel struck an extra beat, as if she had half stumbled, and her steps went faster. He didn’t walk faster, he continued to saunter but he lengthened his stride, smiling slightly. She was afraid.

I’ve always wondered what harassing men are thinking. What’s the motivation behind the grope in the classroom while you’re meant to be learning, the shouted comment on the street, the decision to slow your car to follow a female cyclist? I’ve always found it puzzling as well as depressing that so many other men seek presumably fleeting excitement or arousal at the expense of being such an asshole. This passage provides the best explanation I’m likely to get, and the most frightening—they’re not so much thinking as feeling the sense of power and the desire to laugh. This is also the point where you realize Dix’s name is a pun.

Because Hughes paints such a vivid picture of his world, the reader is forced to follow Dix, strapped into the passenger seat on a journey we’re not sure we want to take, and even empathize with him. A page after Dix stalks the woman, he goes into a bar:

It was a nice bar, from the ship’s prow that jutted upon the sidewalk to the dim ship’s interior. It was a man’s bar, although there was a dark-haired, squawk-voiced woman in it. She was with two men and they were noisy. He didn’t like them. But he liked the old man with the white thin whiskers behind the bar. The man had the quiet competent air of a sea captain.

We can see the bar through Dix’s eyes and share his annoyance at the noisy customers, his pleasure at the old barman. Hughes makes Dix too relatable to be a monster. His thoughts bounce between hints of violence and matter-of-fact observations on life that anyone could share. He looks ordinary too, described as having “a good-looking face but nothing to remember, nothing to set it apart from the usual”. By making Dix so seemingly normal, Hughes sends a message that was radical for her time—predatory men aren’t marked out by physical signifiers (usually those linked to existing prejudices about race, class and mental illness). The boy next door could be plotting your murder. Over the past decade, the new wave of feminism has leveraged social media to allow women to share a flood of accounts of sexism ranging from belittling remarks to serious physical and sexual assaults. And they show, time after time, that other men excused what he did, that everyone refused to believe her, because he was such a nice man.

Hughes doesn’t just use Dix’s dangerous misogyny to generate cheap thrills; she shows how he’s a product of the society that formed him. Brub is Dix’s foil, the good man who’s determined to protect more women from violence. But he doesn’t do it without passing judgment on the victims, noting that the police didn’t take the first murder seriously because the victim was “a girl down on Skid Row… a nice enough kid for the life she lived, I guess.” He’s newly married and tries to limit his wife Sylvia’s movements to protect her from the killer: “Ever since this thing started, I’ve been afraid for her”.

Brub and Dix see women in the same way: as an Other, something to be looked at, judged, controlled, but never fully understood. Dix becomes fixated on his neighbor Laurel Gray, an ambitious starlet who he sees as the cure for his inner torment—“With a woman like that, he might be able to forget. Nothing else brought forgetfulness, only for a brief time”.

Luke Howard, the British man who was widely mocked online for vowing to play the piano in public until his ex-girlfriend noticed, said he was doing it because, “It may sound whimsical but she completely changed my life. My entire world shifted… I wanted to do something that she might see, to let her know how much I love her.” Howard is guilty of nothing worse than misjudged boundaries. (He said in an interview after the outcry that he thought again once he realized his behavior would “absolutely embarrass” his ex). But at its darkest extent, that logic is the same as Dix’s—the assumption that a woman exists in the balm she pours on a man’s emotional needs, not in her ideas or plans.

Feminist critic critic Laura Mulvey identified the male gaze as the the force which shaped cinema. From the classic Hollywood era which forms the backdrop of In a Lonely Place to the modern multiplex, most films position women as something to be looked at. But Hughes offers something different. The curtain Dix’s narrative draws over his violence allows him to stay in denial, but it also means the novel doesn’t dwell on or fetishize women’s murdered bodies. Instead, Hughes gives depth and humanity to the main women characters, giving them a gaze of their own with which to look at Dix. When Dix first meets Laurel, he itemizes her appearance: “Her eyes were slant, her lashes curved long and golden dark.” But she sizes him up, too: “She stood in his way and looked him over slowly, from crown to toe. The way a man looked over a woman, not the reverse.” Sylvia Nicolai is the same: “Sometimes Sylvia’s eyes were disturbing, they were so wise. As if she could see under the covering of a man.”

Although In a Lonely Place tells the story through Dix’s eyes, the reader can see around the edges of his vision. The hints that Dix isn’t as good as hiding his true nature as he thinks he is, particularly around women, keep growing. Part of that is through small acts of abuse and control in his relationship with Laurel. One of the novel’s most frightening scenes is when Dix offers to take Laurel out to any restaurant she wants to go to, then angrily refuses the one she chooses. Dix inwardly complains: “She was acting like a two-year-old, you had to treat her like one. Ignore the tantrums.” But the reader can sense that Laurel’s “tantrums” are something more. Even without Dix’s unreliable narration, Laurel isn’t a ‘nice’ girl by the standards of the time—she’s angry, greedy and sexually experienced. But Hughes doesn’t use this to cheapen her. Working just on the hints Dix overlooks, the reader realizes that Laurel and Sylvia have recognized Dix for what he is, and are actively working to defeat him.

In a Lonely Place was made into a film in 1950, with Humphrey Bogart as Dix and Gloria Grahame as Laurel. It keeps the character names and setting, but nothing else. In the film’s version, Dix Steele is a once-successful screenwriter with a habit of getting into fights on movie sets and with girlfriends. He’s wrongly accused of the murder of one woman, but his neighbor Laurel Gray provides an alibi. This allows the pair to fall in love, until Laurel becomes increasingly frightened of Dix’s violent and erratic behavior and the continued suspicions of the police. Grahame’s performance powerfully conveys the living nightmare of realizing that someone you truly love also scares you, a pattern that’s as sadly common in abusive relationships today as in the 1950s. But the film presents the relationship in the style of a classic Hollywood melodrama, as a doomed romance between two flawed but charismatic people. There are wells of darkness in the original novel that it doesn’t dare look into.

One of my dream films is a faithful adaptation of In a Lonely Place. My perfect version is for it to be directed by Reed Morano—who proved her talent for slow-burning menace and limited points of view with her Emmy win for “The Handmaid’s Tale”—and to star Jake Gyllenhaal as Dix and Stephanie Beatriz as Laurel. The story is timeless, not because it has to be, but because we prefer to ignore the truths it conveys about how our society allows misogyny to mutate. While we wait, do yourself a favor and read In a Lonely Place. It’s a terrific piece of writing, as bracing as Scotch on the rocks. The honesty with which Hughes confronts the danger posed by men like Dix Steele allows us some hope—into those lonely places, haunted by footsteps growing closer, she shines a harsh light.