Parenting by the Books: Slavery’s White Women

You cannot trust white women. We knew that already.

Last week we learned that we cannot trust white women to have any innate interest in dismantling the patriarchy. This lesson was hard and it hurt, but it isn’t particularly new. It’s one told over and over, for example, by black writers in the nineteenth century. I’ve been thinking of those writers this week, especially those who had been enslaved, because they were keen observers of the peculiar form of power white women held. White women, though in large part politically powerless (unable to vote, the literal property of their husbands) were nevertheless culturally powerful. American culture has never respected or valued women, but they have served, then and now, as a moral standard. In the nineteenth-century, she looked like the white-clad Angel of the House; today she’s Having it All, Leaning In.

Black writers and abolitionists understood white women’s cultural power. They realized that one of the key ways to get large-scale political purchase into the idea that slavery was a moral wrong was to show how slavery harmed and undid white women. They wanted to show how hurtful slavery and racism was to all humans, but they also understood how deeply readers would want to fix a problem that seemed to be bringing white women down.

Take Sophia Auld, one of Frederick Douglass’s slave mistresses. When she and Douglass first meet, Sophia is a newcomer to the slaveholding world. She is the pinnacle of white womanhood: caring, benevolent, “a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings.” But slave ownership turns her into a monster. In his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass describes her transformation from a kind woman who tried to help him learn how to write, into a cruel mistress. “The fatal poison of irresponsible power was already in her hands, and soon commenced its infernal work,” he writes.

That cheerful eye, under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage; that voice, made all of sweet accord, changed to one of harsh and horrid discord; and that angelic face gave place to that of a demon.

This particular narrative technique was, of course, highly ironic. Those who had been most harmed — the formerly enslaved — had to embrace a rhetorical strategy that demanded their stories either be supplemented or entirely eclipsed by the world’s favorite story: white women’s inner lives and moral status. The specifics across accounts of slavery vary — sometimes a white woman starts out kind and becomes cruel, sometimes she flames onto the pages already the Devil incarnate, sometimes she is a Quaker, sometimes an unheeded, delicate Angel of the House — but the rhetorical strategy is always the same: show that and how slavery harms white women, to better inspire white readers to want to rise up against the institution.

Sometimes this strategic focus on slavery’s white women is text rather than subtext. In her editor’s introduction to Harriet Jacobs’s 1861 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Lydia Maria Child attempts to draw common ground between “the women of the North” and the enslaved women of the South. She explains that she has worked with Jacobs on her narrative “for the sake of my sisters in bondage, who are suffering wrongs so foul, that our ears are too delicate to listen to them.”

When I teach Incidents (I teach it in nearly all of my classes; it is a masterpiece), I ask my students to spend a lot of time with that sentence. Watch how seamlessly Child moves between the contrary assertions that white women exist in sisterhood with enslaved black women and that white women are also singular, more delicate, fundamentally different. Watch how she does it with that sly pronoun shift to “our.” Watch how the commas work to reassert difference where the language claims connection.

There is irony here, again, given that Jacobs’s narrative features few kind white women, and certainly no “delicate” ones. Jacobs understood her complicated position. She and Child seem to have had a good working relationship, but Jacobs also wove throughout her entire narrative resistance to Child’s deeply felt but often exploitative white female sympathy. In other words, Jacobs seems to have known that she wasn’t only up against the overt cruelty of her perverse former slave mistress Mrs. Flint, but also the white benevolence of someone like her friend and editor Child — a benevolence that so easily shades violent.

So here we are, in the midst of a new iteration of an old problem. White women played a significant role in electing a racist misogynist to the highest office in our country, and we can’t entirely say it’s because they don’t know any better, or even that they are voting against their own interests. Mainstream feminism has focused for decades on making women more politically and individually powerful, and almost no energy in thinking about how to cut through white women’s allegiance to the racist patriarchal systems that value them.

We lack the clarity that Frederick Douglass had, perhaps because the “fatal poison of irresponsible power” doesn’t show its demon face as overtly. Instead, it shows up with a flawless blowout and a superficial embrace of values like #womenwhowork. But this work is never truly for others; it is always for capital first, and for the self and family only to the extent that the work doesn’t challenge the unjust and violent racist patriarchy that prop them up.

The experiences of white womanhood, and white motherhood in particular, often cultivate fear, selfishness, and conventionality. A deep loyalty to the status quo. I have felt and battled this fear and selfishness—this sense that my privileges and my family’s must rightfully be preserved, without full consideration of how that comes at the expense of others. And because the world I live in values my position as a moral figurehead (if not a full person in charge of her own body and more), I am able to protect and care for my children and family in a way that the culture recognizes as best.

But motherhood could mean something so much different than this circular status quo. Adrienne Rich talked about how “the experience of motherhood has been to radicalize me.” Audre Lorde identified how different racial experiences of motherhood could motivate a more ample feminist politics when she observed that “Some problems we share as women, some we do not. You [white women] fear your children will grow up to join the patriarchy and testify against you; we fear our children will be dragged from a car and shot down in the street, and you will turn your backs on the reasons they are dying.” Motherhood need not be the rejection of politics, or the shoring up of conventions and self-serving beliefs. Motherhood can and should be one of the experiences out of which come our most radical commitments to equality, justice, resource sharing, and care.

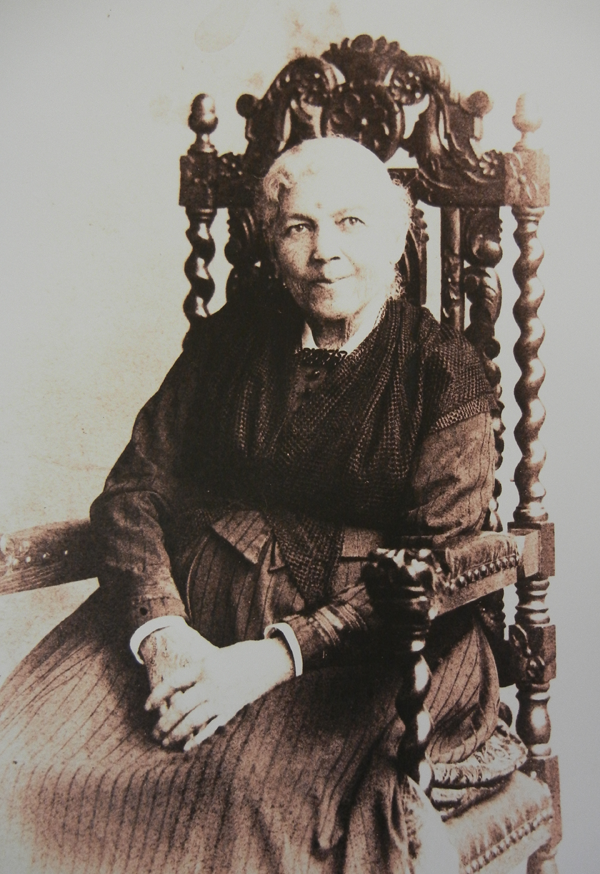

For a long time, I’ve struggled with the end of Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents. She originally drafted the narrative to end with fire and resistance: an account of John Brown’s bloody raid on Harper’s Ferry. Lydia Maria Child intervened here, sending Jacobs a letter: “I think the last chapter, about John Brown, had better be omitted. It does not naturally come into your story, and the M.S. is already too long. Nothing can be so appropriate to end with, as the death of your grandmother.” Jacobs took the advice; Incidents ends on her memories of her grandmother.

My struggle with this ending was initially intellectual; I first read it in graduate school with the full knowledge of its revision history. Child’s idea to reorient the ending around the domestic rather than the agitating political was specifically meant to appeal to white women. Keep them happy, keep them soothed, don’t challenge them to think through John Brown. The story we need them to stay plugged into is the one about how slavery makes them feel. One could reasonably argue that the text loses political power in this revision.

But my perspective on the ending has changed since I first read it. Jacobs’s return to her grandmother insists on the political dimensions of family and domesticity. It does this in part by tracing an important and often invisible black female genealogy. It also refuses to let her white readers forget how different their experiences of family and domesticity have been, that “family” values are not neutral and are rarely nonviolent. Shaped around white women as moral centers, these values, Jacobs knows, don’t just fail to include people of color: they depend on the exclusion of people of color for their power. Under slavery, Jacobs’s family is obviously not protected by law. But even in freedom, it is not legitimated by custom. She is kept apart from her own children, because of financial limitations and employment demands. And she remains judged by the white patriarchal moralism that chides her for having children outside of marriage.

Child wanted Jacobs to end on the family in order to draw a connection back to her white readers. Jacobs followed her suggestion, but to powerful effect. She spins a thread of connection between the white women reading her story and herself, only so that she might more effectively cut it, as if to say, “No, we are not the same.” In this way, her final claim of familial/home feeling is an extension of the most heat-producing passage in Incidents in which the narrator, after confessing her sexual impropriety, turns directly to the reader and wryly exclaims, “Pity me, and pardon me, O virtuous reader!” before offering a thundering anaphora in the second person, directed toward white women (“You never knew…. You never exhausted….You never shuddered”).

Jacobs understood that no amount of vapid “sisterhood” talk would undo racism; she, like so many black writers of her era, saw exactly how white women’s allegiance to patriarchy worked. Hers is a powerful message of fire and resistance around which political rather than consumerist feminism might gather. Let’s stoke it.

“Parenting by the Books” is a series about parenting and classic literary texts.

Sarah Blackwood is editor and co-founder of Avidly and associate professor of English at Pace University.