Anne-Marie Slaughter on Family and Career, and Actually Having Both

“All my life … I’d been the woman smiling the faintly superior smile while another woman told me she had decided to take some time out or pursue a less competitive career track so that she could spend more time with her family. I’d been the woman congratulating herself on her unswerving commitment to the feminist cause, chatting smugly with her dwindling number of college or law-school friends who had reached and maintained their place on the highest rungs of their profession. I’d been the one telling young women at my lectures that you can have it all and do it all, regardless of what field you are in. Which means I’d been part, albeit unwittingly, of making millions of women feel that they are to blame if they cannot manage to rise up the ladder as fast as men and also have a family and an active home life (and be thin and beautiful to boot).”

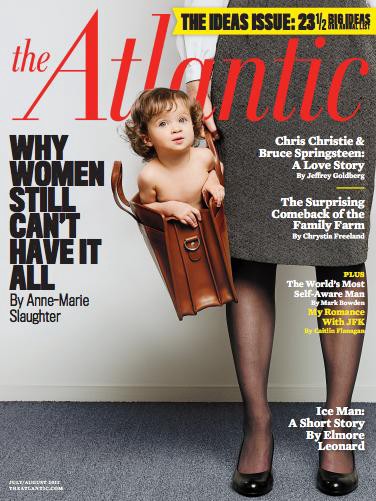

In the cover story of The Atlantic’s summer issue, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” (out today), Anne-Marie Slaughter — professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton, director of policy planning at the State Department from 2009 to 2011, and mother of two — takes an honest and critical look at the ways women are currently encouraged to balance family and career. Summary: It’s not great! The piece is an excellent read, but then please come back here, because we interviewed her about the article, her marriage, raising children, and the practical, doable ideas she has for making things better for everyone. (And it’s too bad there’s no audio here, because she has a wonderful laugh.)

Edith Zimmerman: You mention that you started trying to have kids at 35. Had that been part of you and your husband’s plan? And when did you have the conversation about who would take care of the children during what years, or did it just happen naturally?

Anne-Marie Slaughter: Well, let’s see. First place, I’d gotten married for the second time at 35. So I had been married in my 20s and then divorced around age 30, and then fell madly in love with my current husband somewhere around 1990, and we got married in 1993, and started trying pretty much immediately. It took three years, and I was a tenured law professor, and he was still getting tenure when we had kids, so there was never any question that I was going to have a completely full-time career. And as it evolved, we traded off: I took six months of maternity leave, and he took six months, and we each got a semester off. He was a completely active, engaged father from the beginning. We never had any conversation about who was going to stay home, [but] if anybody ever had to, it probably would have been him, because in terms of who’s earning more money, I would have had to stay on the job.

Right. Did you ever have live-in help, nannies, or neighborhood family day care at any point?

We had daycare from three months on. Very good daycare, one of the things many women unfortunately do not have access to. It was provided first through Harvard and then Princeton, and then since we moved to Princeton and I became dean, we’ve had a full-time housekeeper. Never a live-in. I think we tried a live-in once and it lasted three days.

But we’ve been able to always live and work very close by, and just made it work.

Do you have any advice for what makes your husband such a good partner, or what makes the two of you such a good team as far as raising kids and having full careers go?

Well. Good question. He’s a — well, let’s put it this way. He’s a very secure man! [Laughs] Which is a good thing. And he’s a man who’s always had many, many women friends, and many girlfriends, and is very comfortable in his own skin as a man. He’s motivated by different things than I am. But we were always going to be a team. And it has helped enormously that we’re pretty much in the same business. My first husband was a bio-physicist who also had a medical degree, so we were in very different fields, and it’s been important over the years that Andy and I really share a world. Less so once I became dean and went to government, but essentially we both do international relations, which has been very helpful. But look, we invented parenting as we went along. And we often have different ideas about parenting, but we’re very complementary parents, and I think he’s emerged as a father in ways that probably would have surprised him when we got married.

I also really liked the concept of “putting money in the family bank” with the sabbatical to Shanghai, and I was hoping you could talk a little bit about what you did there, and the most valuable parts of your stay.

Yeah, that was absolutely essential. Again, we were fortunate that we got a sabbatical, although deans don’t normally get sabbaticals. But I pretty much asked for it. Lesson one: ask. But it was so important that the four of us were all in a completely strange place.

How old were your kids at that point?

They were eight and ten. And it was a big deal, you know? We took them out of this nice public elementary school in Princeton, New Jersey, which is a town of 22,000, and we plopped them into a city of closer to 22 million — not quite, but 18 — and it was a country we’d never been to, a language we didn’t speak, a culture we didn’t know. I mean, if we’d gone to Europe — both Andy and I are half-European, and we speak the languages, so we’d be assured adults. But in China it was our older son, Edward, who learned Chinese the best and the fastest and would bargain for us at markets and communicate with taxi drivers. So that in itself was really valuable, but it was more like this incredible, wide-eyed family adventure. Where we shared all sorts of completely ridiculous experiences navigating a very different world, and it really helped us create a tremendous bond. As hard as Washington was, if we hadn’t had China, I think it would have been much, much worse.

So obviously you’d advocate for anyone who has the means and time, or who could conceivably carve out the means and time, if at all possible, to do something like that?

Absolutely. It’s exactly what I said. Putting money in the family bank. And if you can’t take a year, maybe you could take a couple months. Doing something with your family that knocks all of you a little off kilter makes the family become your ballast, and that’s really important.

I’m also curious about the part where you say “a woman would want maximum flexibility and control over her time during the 10 years that her children are 8 to 18.”

I thought hard about that. For some people, they may feel that they really want to be home years zero through five, and then again 13 to 18. I’m not sure there’s any absolute algorithm. In my case, I found it was actually easier when they were young because it was so much more predictable. But, again, I had access to great daycare. For us, it wasn’t until they hit puberty that it just became so much more important to be home. Although, when parents used to tell me that it was more important to be there when they’re teenagers — when you’re the mother of a young child, you just can’t believe that anything could be more demanding than that. [Laughs]

And it’s true that being home when they’re this age, you have tons [more] time, because it’s not like you’re sitting there taking care of them, you’re hoping to get 10 minutes with them as you drive them someplace. So there’s plenty of time to do your own thing, it’s just that you need the flexibility.

The Mary Matalin quote at the beginning of your piece from when she was in the car, freaking out — “I finally asked myself, ‘Who needs me more?’ and that’s when I realized, it’s somebody else’s turn to do this job. I’m indispensable to my kids, but I’m not close to indispensable to the White House” — in my mind raised a tricky question. Because if your career isn’t something that you’re the best at, and it’s more just a job you’re doing than something particularly close to your heart, but you always WILL be the best, presumably, at raising your own children, why isn’t the choice to stay home more immediately obvious?

If Women’s Liberation meant anything, it meant giving women a full range of choices, so that if a woman thinks that that’s what she’s best at, and that’s what she’s happiest doing, then we absolutely need to validate that choice. And many women have written about that. About the importance of not buying into the idea that going to work is only done outside the home. At the same time, the whole reason there was a feminist movement in the first place was that overwhelming numbers of women found that they wanted to have more choices, so it’s not like we haven’t tried a world in which women stayed home. And I think some will, and great. I would go crazy. If I stayed home. I would go ab. Solutely. Crazy. I think my own mother, who became a professional artist, would have been happier in many ways if she’d had both a career and children when we were young, because she’s a very creative person and I think she needed an outlet other than in the house.

It’s a question of following your own instincts. But I’m pretty confident that given the right conditions, a huge number will choose to do both. But they’re not going to choose to do both if it keeps coming down to a choice between one or the other. And that’s what I meant by as long as you give me flexibility, I can do just about anything. I can work and then go home to be with my kids, and then go back to work later, or take a business trip and work like crazy, but then spend a couple days being a mom. And many women — I think virtually all women — can manage that. The problem is where they work. What Mary Matalin said, which is exactly what I kept saying to people, is “what am I doing? There are lots of people who want to be director of policy planning, but there’s nobody volunteering to be Edward’s mother.” And even if they were, I wouldn’t let them! Obviously many, many women don’t have any choice about working, but those that do should hold out for work that’s fulfilling.

So people read this article, they finish it, they think, “yeah, this is great!” What then should they do? Should they take the most workable points from the piece and present them to the people who make policy at their jobs?

That’s great. If you’re in a leadership or management position, you should set about undoing the artificial segregation between work and life. In little ways. Like I mention in the piece, whenever I’m introduced, I make sure that people say that I have two sons, and I often say something like — as Hillary Clinton said — “that’s my real life.” And that’s enormously important. The minute she said that, I thought, “yeah, that’s exactly the way I feel, and it doesn’t make me any less of a professional.”

So you can make very clear that you can be the world’s most accomplished professional, and care about your kids, and talk about your kids — not to excess, I’m not suggesting we all bore each other silly. And you can embrace the idea that men and women may choose to delay a promotion to take a different career route while they’re caregivers. And, again, that could apply to taking care of your parents as well as your kids. I manage on the principle that family comes first, and I’ve never had any problem.

If you’re working [in a non-managerial position], I think absolutely you can get together with other women and men — I think you can enlist the fathers — and sit down [with policymakers] to have a conversation about more flexible time, which a lot of places are doing. Take it on directly. This culture of facetime and time macho — talk about how measuring people in terms of time management instead of time spent is a better way to go.

Most important is when thinking about the arc of your career to think not “when am I going to have to drop out?” but “how am I going to build in the flexibility to be the parent I want and the worker I want, and stay in the game?”

I just have one last question, which I hope doesn’t sound leading, because I really just mean “How can I be more like you?”

[Laughs]

But is there anything you would have done differently at any point along the way?

Hm. No. What has really shaped my life, and I just realized as you asked this question, and I never thought about it this way before — shaping my decision to leave Washington and even to write this article — is that I’ve always refused to do things because other people expected me to do them. I thought I was going to be a lawyer, I always planned to be a lawyer. Always, always, always. And I wanted to be a lawyer who would then go to work in the State Department, and I was going to go work for a big New York firm, and then work with a partner and go in and out. That’s how a lot of people got to do foreign policy in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, all the way back for decades. And when I went to work for a big New York law firm, I realized, “I don’t want to do this.” [Laughs.] “I can’t do this. I’m not going to be happy doing this.” So I hung out for four years at Harvard getting a degree, but basically trying to figure out what on earth I was going to do, and I ended up being a professor, and I loved it. But the point is, when I wasn’t happy, I did something about it. And that’s been true here, too. I had a dream job and I loved it, but I was very much not happy and realized that even contrary to my own expectations for my own career, and I think many people’s expectations of me, I didn’t want to keep at something when I felt very unhappy, and that it was simply the wrong thing for me to be doing. I tell my students: always follow your passion, but it’s not always clear what your passion is.

So if you wake up in the morning and are really miserable about going to work, you need to have the confidence and the fortitude to find something else. And to believe that you will find something else. And if that means you need to take time out to be with your kids, or if you’re with your kids, switching careers, you can do it. I think women often insist that their work have meaning and purpose, and that they feel like integrated human beings. And that they’re better off, and our society is better off, when they have the courage and the confidence to try.

Read “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” at The Atlantic.