Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Ronald Reagan Plays the President

by Anne Helen Petersen

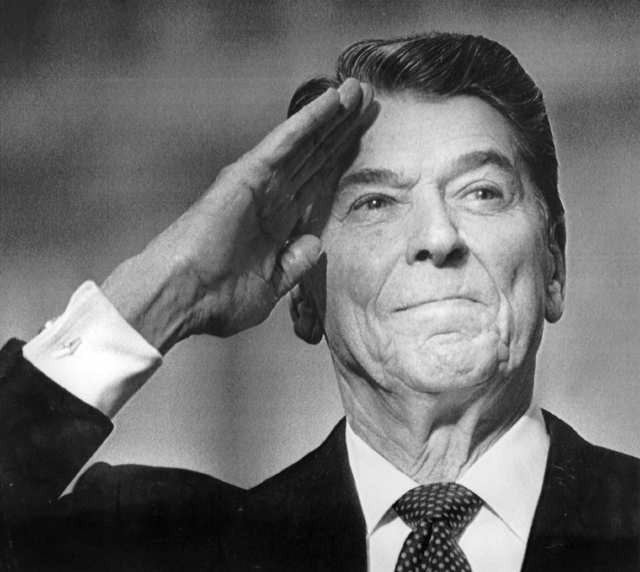

When you think of Ronald Reagan, you think of jellybeans, Nancy’s power suits, and self-satisfaction. You think of all the contemporary Republicans who miss him and what he seemed to represent, along with a sort of composure and telegenic presence that even Clinton couldn’t replicate. You think of trickle-down economics, Iran-Contra, and a political legacy so potent that criticizing him is in many circles still considered a moderate form of blasphemy.

What you might not think of is Reagan frolicking on the beach in white swim trunks, playing matchmaker for Bette Davis, or divorcing one of Hollywood’s sweethearts. But Reagan did all of those things — and others even more absurd — during his tenure as a rising movie star. And while Reagan’s film career was, let it be said, totally underwhelming, what he did with his Hollywood status was not. He used his position at the head of the Screen Actors Guild to screw over a whole swath of Hollywood actors, and his behind-closed-doors collaborations with MCA head Lew Wasserman did as much to change the way that Hollywood worked as did the studio system’s demise. When he was just President of Hollywood, he swindled those he was supposed to protect. In this way, his Hollywood history prepared him (at the risk of sounding cliché) for the role of a lifetime: that of the seemingly competent, wholly compassionate President.

While Reagan was in Hollywood, he was never quite a star. He operated on the fringes, always almost making it. But he learned the way the system worked and which people to befriend, and he picked up the most brilliant secret of the trade: how to manufacture an image, and how to wield that image to get people to like you. If you think about it, all the recent Presidents resemble studio-made stars — plucked from the farm leagues, groomed, and made to represent an idea and societal attitude much larger than themselves. Their images reconcile the contradictions inherent to ideology: Marilyn Monroe was the virginal whore, and Reagan was proof positive that cutting services to the poor could be compassionate. And the stars who embody ideologies most adroitly, most seamlessly — those are the stars who endure, as Reagan has, and eventually come to signify a different sort of meaning for a new generation. And whatever Reagan means to you today, by the end of this piece he may mean something slightly different.

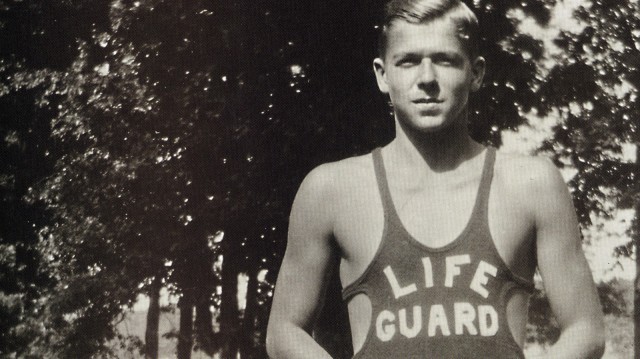

Reagan had a standard (old school) presidential background: He was born in small-town Illinois to a salesman father and a do-gooder mother. According to popular lore, Reagan always seemed to have had a strong sense of “right and wrong,” and often brought African-Americans who weren’t allowed to stay in the local inn back to his home, where his family would lodge them for the night. He went to high school and did high school things, like becoming a lifeguard and saving 77 people (he carved a notch for each one, in case you think he’s lying).

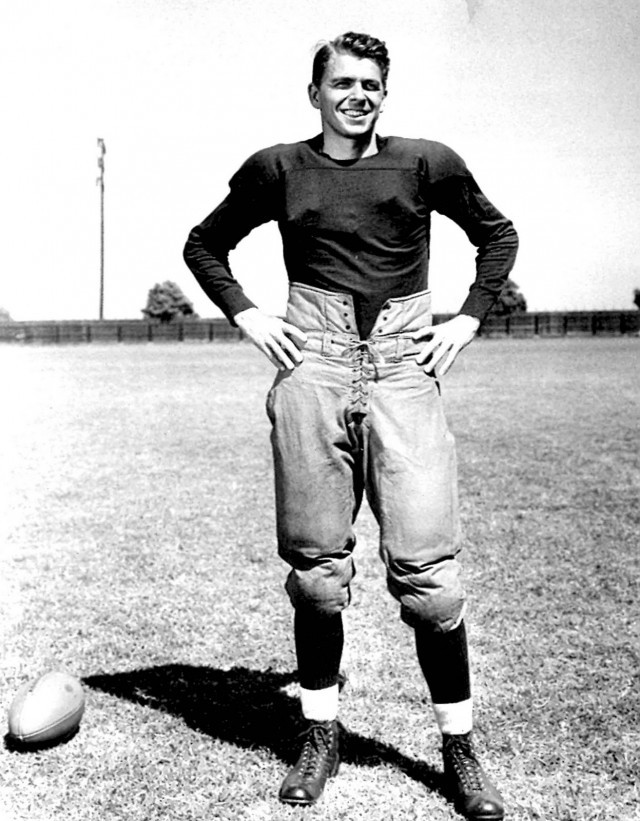

He went to a small Christian college and dominated the hell out of it: frat boy, cheerleader, football player, student body president — you name it, he did it. He was like Max Fischer at Rushmore Academy, only popular and goyish.

Reagan parlayed his college success into the most collegiate of post-college jobs, working as a sportscaster for the University of Iowa, then calling Cubs games on local radio. While on the road, he filmed a screen test, signed a seven-year contract with Warner Bros., and suddenly there Reagan was, shirtless all over Hollywood.

He may have been shirtless, but he wasn’t necessarily getting good roles. The Warners tried to sell him as “the new rave of Hollywood” in Love Is in the Air, the first of 19 films he’d complete over the next two years. He was flatly handsome, broadly palatable, and wholly unremarkable: the perfect B-lister, and the equivalent of today’s soap opera star, like that guy who keeps taking off his shirt on Hart of Dixie.

Sometimes he got to play a supporting part in an A-film, as he did in Best Picture-nominee Dark Victory, half-heartedly and half-drunkenly pursuing Bette Davis’s society-girl heroine. He spent a fair amount of time playing (big stretch) radio announcers, and landed a choice role as a young VMI student in Brother Rat, the name given to freshmen who totally never get hazed during their first year of college.

(Having dated [long story] a Brother Rat at one point in my past, I can say, with authority, that they were not allowed within that sort of proximity to women who looked like Jane Wyman. I can also attest to the fact that they weren’t allowed to talk to me on the phone for periods of longer than five minutes, which is really helpful for long-distance relationships during the first three months of college. That is all the truth I can tell re: Brother Rats.)

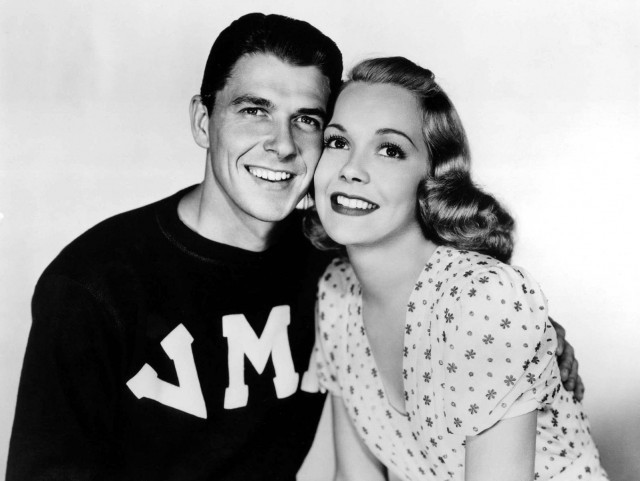

Brother Rat also introduced Reagan to that pretty, narratively improbable lady in the picture above — a woman who would eventually become his (first) wife.

Jane Wyman would go on to become a major melodramatic star (Magnificent Obsession! All That Heaven Allows!), but in 1939, she was right on Reagan’s level, working her way through bit parts and B-movies for Warner Bros. She and Reagan married in January 1940; their wedding picture featured in the back pages of Photoplay the way reality stars’ weddings make the back pages of Us.

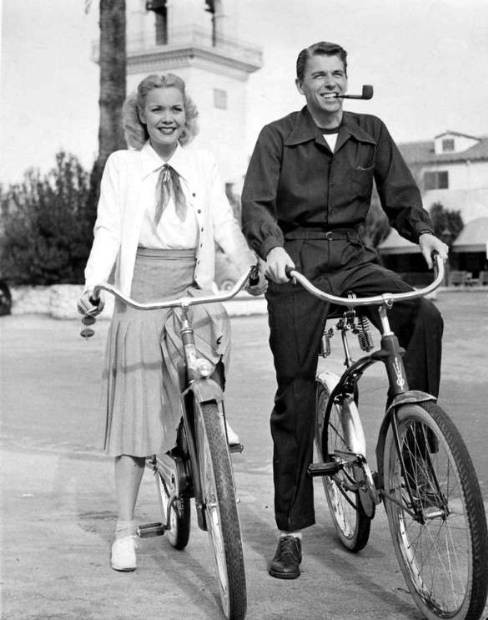

The publicity wasn’t much, but it was something — enough, in fact, to pair them together for Brother Rat and Baby (I AM SORRY; THAT SOUNDS GROSS) the following year. Plus they did all sorts of awesome, very public, totally barfy couple stuff together, like playing duets on the piano and riding bikes while smoking pipes:

At this point, Reagan’s star was slowly rising: He’d had a supporting role in a Best Picture nominee, he had a starlet wife, and he had finally made a name for himself in the biopic Knute Rockne, All American.

Now, Knute Rockne was a living, breathing, very Norwegian-named Notre Dame football coach. Everyone loved the guy; everyone loved Notre Dame; everyone loved the players who distinguished themselves under Rockne, including George “The Gipper” Gipp. The Gipper was one of the greats, but he became even greater when he died from pneumonia two weeks after winning the title for Notre Dame. And its gets better/more melodramatic: On his deathbed, he asked Rockne to tell the team to “Win one for the Gipper.” Deathbed pleas for football victory!

And guess who played The Gipper: our boy Ronnie.

A virile, All-American boy; a tragic death; lost potential — that’s the stuff of legends. And over time, that legend would became intertwined with Reagan’s own. The nickname stuck, and years later, as his second presidential term came to an end, Reagan told then-Vice President George H. W. Bush to go out and “win one for the Gipper.” Wyman gave birth to a daughter, Maureen, in January 1941, and Reagan starred as a double amputee in Kings Row — widely agreed to be his best film, in part, no doubt, for his ability to rock this bathrobe and smoosh his face with Ann Sheridan’s:

But seriously, this is film is crazy. There are poisonings, weird doctors, other even weirder doctors, weird medical students, railroad accidents, suicides, and rich orphans. No matter how far-fetched the plot may have been, it made Reagan (and his natty bathrobe) an on-the-cusp star. But just as he was starting to gain momentum, the draft board got him. He had bad eyes, though, so he wouldn’t have to serve overseas, and spent a few months as a desk monkey in California before getting transferred to the First Motion Picture Unit — a fancy name for the people responsible for making propaganda and training films for the armed services.

The First Motion Picture Unit, and the Hollywood/armed forces collaboration of which it was a part, is nearly impossible for us today to truly understand. If you were drafted and you had any Hollywood skills, you were often placed in the Unit — in part because they needed people who could direct and edit, but also because a gunned-down star would be horrible for morale (see: Leslie Howard). Some stars (Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart) did become veritable war heros, but most were put to work on the homefront in the Unit or, as Reagan later did, traveling the country on non-stop War Bond tours.

With Wyman at the ‘Tales of Manhattan’ premiere in 1942.

Think of those over-the-top, thunder-in-the-background commercials for the Marines that you see on TV. Now think of those commercials in full-movie form … and imagine they’re actually effective. Winning Your Wings, starring a strapping Jimmy Stewart, apparently prompted 100,000 men to sign up for the Air Force. Reagan appeared in a few films, but mostly took care of organization and narration. But he served his country — a fact that would prove essential to his political life.

The end of the war should have marked a new beginning for Reagan’s career. But like many stars absent from the screen for four years — most notably, Stewart himself — his momentum was lost.

Which isn’t to say that he didn’t try to regain it:

Looking (quite lustily?) at his co-star in A Hasty Heart;

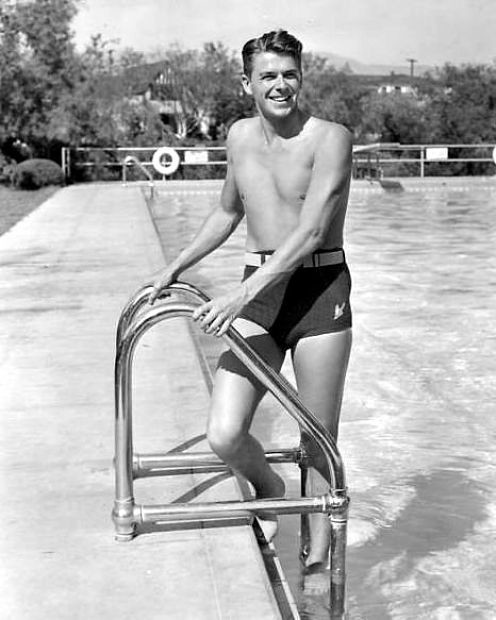

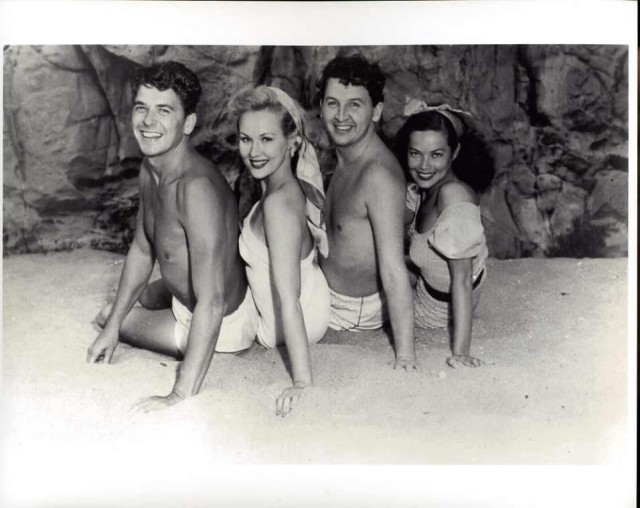

Dominating the white bathing suit bottom in The Girl From Jones Beach;

Keeping his waistline in shape with unidentified high-waisted compatriots;

Playing with large balls with unidentified busty ladies;

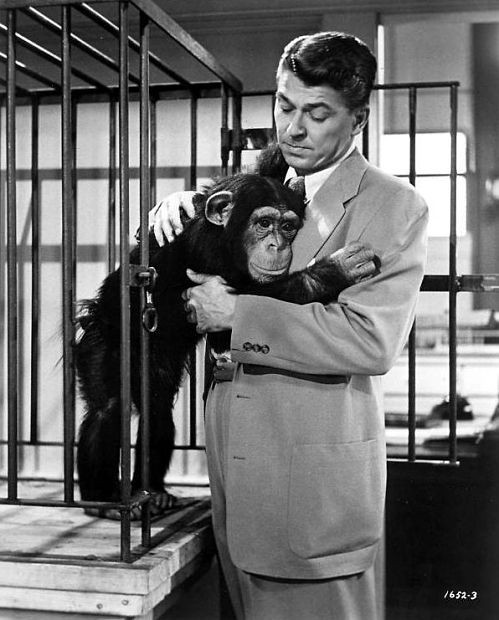

And becoming part of your childhood memories in Bedtime for Bonzo.

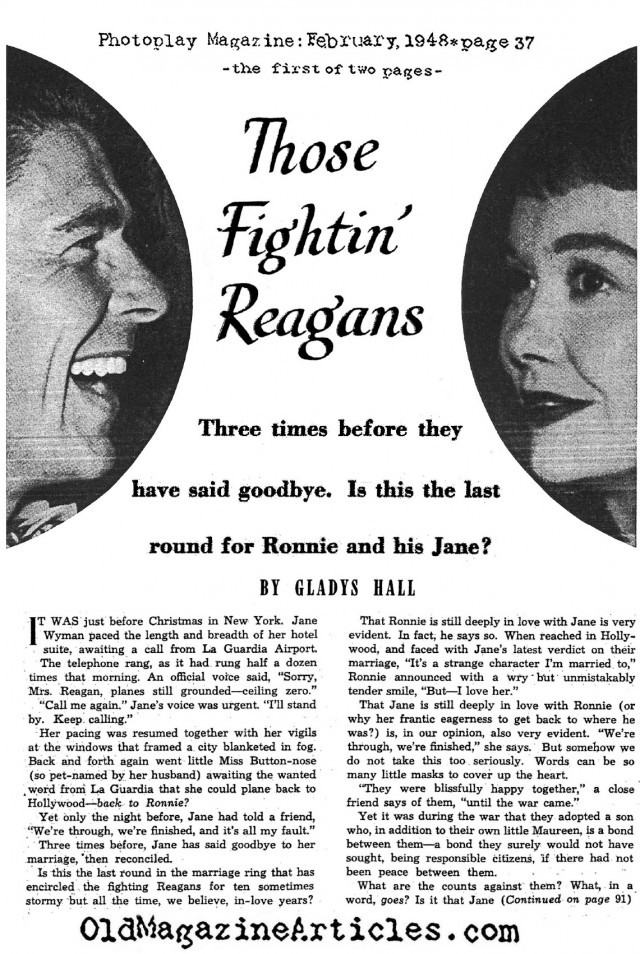

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Among all this ludicrous filmmaking, Reagan made two life-changing decisions: In 1947, he became president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), and the next year, he and Jane Wyman divorced.

As this awesome Photoplay article makes clear, the two had been on the rocks for some time. The woeful prose, it never fails to slay me: “Words can be so many masks to cover up the heart.” Other sources claimed that Wyman was sick of Reagan’s obsession with politics — it was all he ever wanted to talk about; he was, as Wyman told her friends, a total dullard. Or, perhaps, they couldn’t figure out how to make things work after the birth of a second daughter, Christine, who lived only a day. The couple adopted a two-year-old son soon thereafter, but it apparently wasn’t enough to keep them together.

Thus began a four-year period of Reagan bachelorhood. He met his future wife, Nancy Davis, in 1949, but he still purportedly spent some time fooling around — perhaps most scandalously with the very young Piper Laurie, whom he met while filming Louisa in 1950.

Key statistics related to this encounter:

18 = Laurie’s age.

39 = Reagan’s age.

40 = Number of minutes Reagan claimed he’d last in bed.

“Very expensive” = Purported cost of the condom Reagan used.

“Without grace” = Laurie’s verdict on Reagan’s bedroom repertoire.

Granted, all of this information came from Laurie’s own memoir, so take that as you will. Reagan had met Nancy Davis the year before (she’d approached him in his capacity as the president of the Actors Guild to help clear up a clerical snafu that had mistakenly put her on the blacklist).

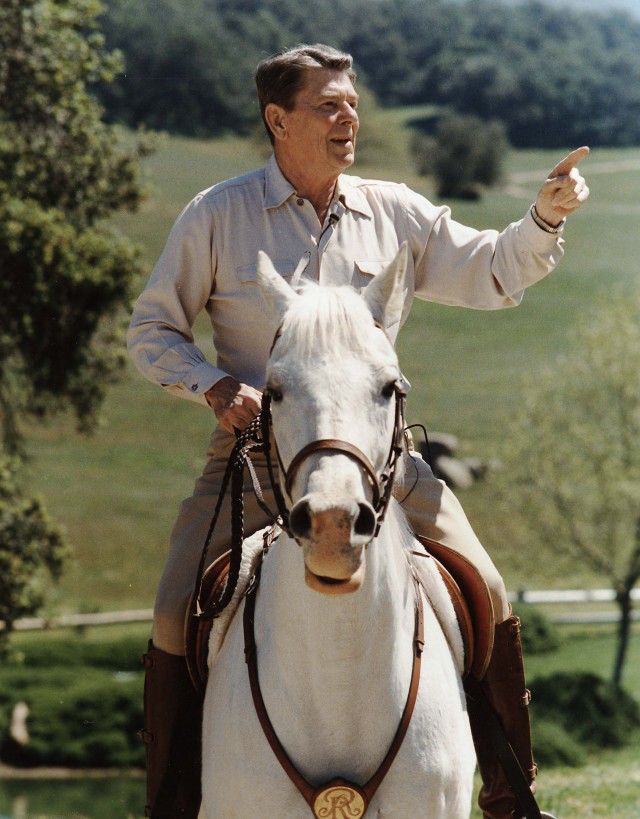

At some point after their 1949 meeting, before or after his dalliance with Laurie, they started officially dating. Modern Screen called Davis “the doe-eyed, gentle-voiced, sweet-faced young actress who has Ronnie Reagan’s heart tied up with love knots.” Apparently, however, Davis was known around Hollywood as “a decorous, unexciting and unglamorous mouse, built for convention and not for speed” — a misconception that Modern Screen labored to correct. Davis got caught speeding in her convertible! She rode horses! Sometimes she even overslept! She was, in other words, Nancy Reagan in the making.

Why yes, that is William Holden as Best Man.

The two would marry in March of 1952, and a baby girl, Patti, was born in October. (That is some scandalous math you’re doing in your head right now.) This also happened to be the year of Hong Kong, notable only for its photographic traces:

I. can’t. even. I seriously can’t even start. I can, however, tell you that these photos single-handedly convinced me to write this piece.

But yet again, I’m getting ahead of myself. Because throughout this period, Reagan’s political ambitions were exploding. He had first become involved with the Screen Actors Guild in 1941, he was elected vice president in ’46, and then he was elected president in ’47. He would hold the position until 1952, and then would hold it again in 1959. Other SAG presidents have served as long, but none has served during such tumult.

Politically, Reagan had long leaned liberal: He had repeatedly voted for FDR and supported the New Deal. He had been a member, elected representative, vice president, and president of a union. But in 1947, his politics turned. A craft union member who was on strike threatened to throw acid in his face — a fact he later recalled as the “turning point” in his shift from the left to the right. And over his seven terms as SAG president, he worked to keep the organization neutral, cutting deals with producers in explicit or implicit exchange for favors. As George Dunne, chronicler of Hollywood’s labor movement, observed, SAG “was operating in conspiratorial cooperation with the Hollywood producers to destroy what was the only honest and democratic trade union movement in Hollywood. And Reagan was part of that movement.”

But that wasn’t all he was doing. If you’re familiar with film history or, for that matter, American history, then you know about McCarthyism and the blacklisting that went on in Hollywood. Condensed version: The government thought it was most imperative to get any Reds out of Hollywood, lest they sneak some of their dirty communism into the nation’s cultural products. Thus anyone with any past affiliation to any vaguely Marxist/Leftist group (including lots of progressive-minded ones from the ’30s) could be blacklisted — meaning effectively banned from working in Hollywood. Some people testified and “named names,” while others refused on principle, which ended in their own quasi-blacklisting. It was all quite repulsive yet justified in the name of national security — kind of how I think we’ll look back on The Patriot Act in 50 years.

And it happened, at least in part, because of Reagan.

In 1947, Reagan and Walt Disney testified that communists were a serious threat to the industry; in private, Reagan advised the FBI that “lacking a definite stand on the part of the government, it would be very difficult for any committee of motion-picture people to conduct any type of cleansing of their own household.” As a result, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) pursued its above-mentioned persecution of those in Hollywood with past and/or present affiliations with communism, eventually leading to the blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten.” Reagan then led the charge for all officers of the Screen Actors Guild to swear a “non-Communist pledge,” approved by the SAG membership on November 17, 1947.

I realize that it’s easy to look back on this period with self-righteous indignation. I realize that Reagan was by no means the only friendly witness who facilitated the culture of fear and suppression in Hollywood and America at large. But it seems clear that without the support of the president of the Screen Actors Guild, things could have proceeded differently. Reagan was, in the words of film historian David Thomson, “a bureaucrat of McCarthyism and a shortsighted searcher after redness.”

Reagan’s next slimy move came in 1952, when he crafted a backdoor deal with Lew Wasserman, head of MCA, that would dramatically shift the course of the television industry. MCA was the reigning agent powerhouse, and Wasserman was its captain. Wasserman had the foresight to see that the future of television was not in live programming — which much of it had been up to that point — but filmed programming. Filmed programming was more expensive, but you could rerun it forever. But Wasserman didn’t just wanted to serve as an agent for those making television, he wanted to dominate the industry. And to do so, he’d have to turn MCA from a talent agency into a studio.

One of the few pictures of young Lew Wasserman in circulation.

One (huge) problem: SAG rules prevented talent agencies from getting into film production. You could imagine why: It’s a straightforward conflict of interest. (For example, let’s say MCA represents Blake Lively. They’ve landed her some good, high-paying roles in the past, and now they want to call in a favor for her to appear in a new show … that MCA is producing. Her agent isn’t going to push for a higher salary, because a higher salary means a cut to the MCA profit margin. Stinky business; no good for actors.)

SAG had established the rules for film production, but television production was still very much the Wild West in those days. In 1949, MCA had started a small production arm (Revue), but it produced a fraction of what Wasserman envisioned. Wasserman also knew that the Wild West was about to be tamed. If he didn’t figure out a way to get around the rules soon, he’d never have his TV empire. So he found a loophole: In the past, agents could apply for an exception to the SAG rules on a film-by-film basis; Wasserman would thus request a “blanket waiver” for all Revue Productions going forward. As Connie Bruck explains, (go buy When Hollywood Had a King)…

“[H]is control of talent would give him an unbeatable advantage in TV production, and his TV production would only strengthen his hand with talent; these intertwining activities would create a system so powerful that someone not similarly situated could not compete in a meaningful way. As a business model, its only weakness lay in its transparency; it was impossible not to see how overreaching it was.”

In other words, it was straight up monopolistic, probably even illegal. And certainly, if passed, exploitative of talent. You’d think that maybe the head of the Screen Actors Guild might protest its passage?

But you’d be forgetting that the head of the Screen Actors Guild was Ronald Reagan. Reagan, client of Lew Wasserman, with a film career on the decline. To sweeten the deal, Wasserman promised Reagan that he’d support “reuse payments” (a.k.a. small residuals for screen performers). But that deal was hush-hush, and Reagan still needed to convince the rest of the SAG board to approve the blanket waiver. Luckily, the vice president of the board, Walter Pidgeon, was also an MCA client. Pidgeon had just been released from his contract with MGM — like hundreds of other stars and below-the-line talent, he was cut loose to save money in the wake of the studio system’s demise. He was desperate for work, even if it meant letting MCA rule the business. Between Reagan and Pidgeon, the blanket waiver passed.

And Reagan reaped its benefits. Again, in 1952 Reagan was coming off a chimp movie. He needed a career rejuvenation, and he needed it fast — and Wasserman was poised to provide it. They tried to put him in Las Vegas, the new “mecca” for performers of all types, but he was labeled “an omelet.” Take that as you will.

MCA thus used the newly approved blanket waiver to make him a show: General Electric Theater, an “anthology” program (think Masterpiece Theater; in the ’50s, these were all the rage) for which he served as both host and star. The Hollywood gossip mill immediately started churning: sure, this guy was the former SAG president, but he was also a B-list star at best. How’d he land a choice program? OH YEAH, THAT’S RIGHT, IT’S BECAUSE HE WAS IN BED WITH THE RULER OF HOLLYWOOD.

And so it went. The newly married Reagan was newly resurgent, and after a few years, he became a co-producer of General Electric Theater, making him a very rich man. His career, his image, his fortune — all saved because of his backdoor dealings with Wasserman. These dealings might have benefited a few stars, especially those already under the MCA umbrella, but they also led to MCA’s hegemonic rule of Hollywood, which not only exploited a certain class of talent but also led to a highly derivative television landscape, filled with Westerns and game shows. I am, in other words, encouraging you to blame Reagan for the shitty television of the late ’50s and ‘60s.

Reagan was living high on the hog, enjoying the fifth year of General Electric Theater. He had left the SAG presidency after engineering the blanket waiver in 1952, and was growing his family with Nancy. But in 1959, a new opportunity for SAG to screw over its members was coming to a head. The issue was long-brewing: Ever since the studios had started selling the rights to their films to the television networks, the stars of these films had been lobbying for rights to a portion of the residuals, which would give them a relatively small amount of money every time a studio sold the rights of a film in which they had appeared.

MCA was the heavy hitter in the negotiations, having purchased the rights to Paramount’s pre-1948 library and supposedly engaged in talks for Universal’s. The decision was made to call Reagan back to the ranks, presumably in hopes that he could sway MCA and Wasserman toward a better deal for the actors. As Reagan recalled in his memoir, he didn’t want to return to the SAG presidency, as his “career had suffered” during his last tenure. But he called Wasserman (still, remember, his agent), and Wasserman advised him to buck up and take the job.

UM. ARE YOU GUYS SMELLING SOMETHING FISHY? Maybe some high-class, bastard fish that eats all the other, small, eager fishes and then pretends it’s the nicest fish in the pond?

Reagan fails to manufacture a deal that satisfied the guild members; they go on strike. For six weeks. Everyone’s pissed and anxious. Finally, he cuts a deal: The studios would put together a pension/welfare plan of sorts for the actors, and in exchange, the actors would give over ALL RIGHTS to ALL FILMS made before 1960. It was a mindbogglingly good deal for the studios, and a huge eff-you to the actors. And that, Scandals readers, is what they call screwing the pooch.

To add insult to injury, Reagan resigned from the SAG presidency in order to move into a joint production partnership with — you guessed it — MCA. When the United States government summoned a grand jury to investigate MCA’s monopolistic business practices in 1962, Reagan was called to the stand. In his testimony, sealed for 25 years, he admitted that he had been cut into a 25% ownership deal of General Electric Theater in … wait for it … 1959, after discussions with Wasserman.

What can we do with this history? For one, we can realize that Wasserman was a genius. He was manipulative and exploitative, but the man was brilliant. And the most brilliant men know how to get others to do their work for them — especially those more handsome, affable, and popular than they are. Karl Rove understood this with George W.; Wasserman understood this with Reagan.

And for the next 40 years, Reagan would prove his ability to ventriloquize his handlers’ ideology again and again. Robert Gilbert, a labor lawyer responsible for briefing Reagan on key issues during his tenure at SAG, explains that Reagan could make a “two-hour speech based on a 15 minute briefing — and it was fabulous. This guy could absorb what he was told and regurgitate it. He was very glib and articulate — even if he didn’t understand it.” And that’s just it: Reagan could act; he could memorize lines on the fly. He knew how to play to the camera, he didn’t flub his lines, and if he did, he know how to gracefully improvise. He wasn’t qualified, per se, as a politician — but he sure was good at acting like he was.

Reagan rose through the political ranks, standing on the shoulders of Wasserman and the “Hollywood cabinet” that Wasserman arranged to rally around him. Wasserman would facilitate his election as president, and, once Reagan was in office, would call upon Reagan’s favor yet again. This time, they set in motion the deregulatory policies that have, over the last 30 years, led to the rise of massive media conglomeration.

Wasserman, Nancy, and Ronnie hobnobbing like old times.

Without Reagan and the policies he pushed through at Wasserman’s behest, there would be no Rupert Murdoch — or at least no News Corp. the way we know it. No massive Disney empire. Six entities would not provide the vast majority of your entertainment. The media landscape could conceivably look much different — more diverse, and less obsessed with synergy and cross-plugging and multi-platform hits. Whether in 1947, 1952, 1959, or 1984, Reagan’s interests were Wasserman’s interests — and those interests were very rarely the interests of the citizens Reagan was entrusted to protect.

You could argue that Reagan wasn’t doing anything new: Shady deals are politicians’ ways and means. But I think there’s something in Reagan’s rise to power that’s far more disturbing, far more insidious, and far more illuminating of the American cult of stardom.

I obviously love stars, and what stars can mean to different swaths of people. But what draws me and other scholars to study them isn’t their glamour but their tremendous ideological potency — a potency that can be wielded, at the risk of sounding melodramatic, for good or for evil, for justice or for exploitation. Oftentimes, the star him- or herself has very little to do with what their image is made to represent, which, as so many of these columns have pointed out, can also be stardom’s tragedy. Reagan was obviously manipulated by others, but he did not hesitate to manipulate in turn. What he did to the members of the Screen Actors Guild, he did again, only on a larger scale, to the people of the United States. And because he was a star, because his image of compassionate American goodness was so strong, it was easy to see what he appeared to represent instead of what he was actually doing.

The same was certainly true of George W.: He was, after all, the president most people wanted to “have a beer with,” which is just another way of saying “this star: he’s just like us!” Clinton’s impeachment was, in large part, due to a focus on what his actions seemed to indicate about the integrity of his star image — not about his capacity to govern. Obama rode the energy of his star machine into office, but failed to manifest the central tenant of that image — hope — on a daily basis. He concerned himself with governing: with the long-term, thoroughly unsexy reforms that would engender hope as opposed to simply paying lip service to it. It’s been a disappointment to a lot of people — many of whom got off the Bush Star Train to hop on Obama’s. Obama may always be a mediocre star, but he might yet be a great president. And as for Romney: He’s the best, most pliable, most versatile actor to run since Reagan. Take that as you will.

Thomson claims that with Reagan’s election, “the fraudulence of the presidency was revealed so that the office could never quite be honored again.” It’s a hard idea to hear. But I fear it might be true.

Previously: The Gloria Swanson Saga.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.