Scientology and Me, Part Two: What Scientologists Actually Believe

by Stella Forstner

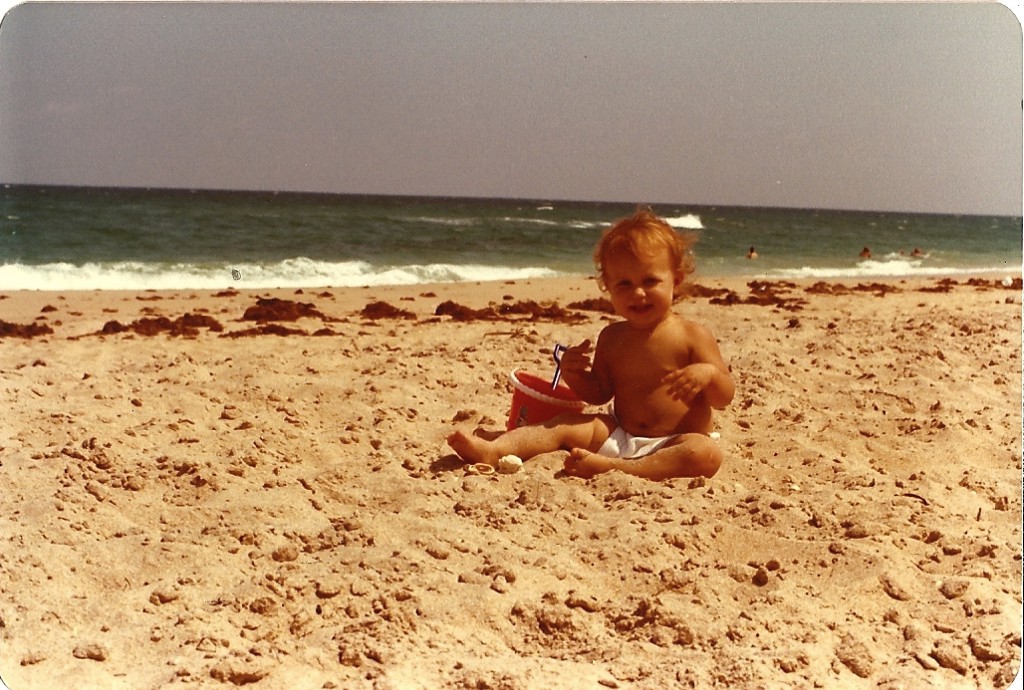

[image from my personal collection — I couldn’t find one with the OT t-shirt!]

Previously: Part One, Growing Up in the Church.

As a child of two Scientologist parents, a child born into a room quieted in preparation for the return of a reincarnated thetan, I grew up fluent in the Church’s specialized vocabulary. As a toddler I accompanied my mother during her training at the Flag Land base in Clearwater, Florida, and at the Los Angeles center, wearing a t-shirt that read “future OT,” a bit of gobbledygook that any Scientologist worth their salt could immediately translate as indicating that I was destined to rid myself of my ‘reactive mind’ and go ‘clear’ before ascending the ‘bridge to total freedom’ to reach the level of ‘OT’ (operating thetan). Had I chosen this life of intensive Scientology study and training, I might only be in slightly more debt than student loans have left me, but the choice was never mine to make: I was too young to have actually taken Scientology courses before my mother left the Church, and when my father later urged it, I was not allowed to on account of my mother’s enemy status.

Growing up surrounded by the language and ideas of Scientology, I developed the capacity for linguistic register-switching: the ability to rapidly, even unconsciously, shift my language when I moved among different social domains. To this day it’s like a door opens in my brain when I’m with my parents, allowing the use of those specialized terms, and closes again when I’m with friends, preventing me from throwing out an embarrassing engram reference by accident. But I still sometimes get confused. One day not too many years ago I had to ask my mother if “enturbulate,” a term that suggests being so agitated you are unable to do something, was a real word or a Scientology word and damn it, I was enturbulated when she told me it wasn’t. I heard and used the term so frequently growing up that it had come to be linked with an actual and specific psychological state that I felt and experienced as enturbulation. If it wasn’t a real word, did that mean other people didn’t feel it? How could I explain it to them without these shared terms?

Of course I can explain that state without resorting to the specialized language of the church — I just did. In reality much of the basic terminology that Scientologists use is easy to understand for those of us raised in the Euro-American tradition. The founder of Scientology, and its predecessor, Dianetics, Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (or LRH, as I knew him growing up), while famously a marginally successful writer of science fiction before he turned to creating a new ‘science of the mind,’ was more broadly an American of the 20th century. Hubbard neatly fused Western psychology and Eastern religion, drawing on (which sometimes looked a lot like stealing from) numerous traditions to create a ‘scientific religion’ that appealed to the quintessentially American obsession with the self, a current that connects Emersonian self-reliance to Oprah-ian self-fulfillment. Like any religion, it gets more complicated and esoteric the deeper and higher you go, but the fundamental principles are quite simple. There is nothing in them so mind-boggling as the Buddhist imperative that you purge yourself of the desire to even desire to stop desiring or even the Christian requirement to accept a three-pronged god.

When people find out I was raised in Scientology they are almost uniformly intrigued; over the years I’ve developed a simple spiel to explain what it is that Scientologists actually believe. Scientologists believe, first and foremost, in an essential, reincarnating self, called a thetan, which is basically a soul, and in an animalistic, base, and impulse-driven ‘reactive mind,’ which is essentially the unconscious. By storing up all the bad things that have happened to you in your life, the reactive mind dictates your actions according to a system of stimulus-response, bypassing your conscious analytical mind. Scientologists believe that when you have become free of your reactive mind, you achieve the state of ‘clear’ and become an ‘operating thetan’ (OT). In the earliest formulation of Dianetics, clear was the highest level one could achieve. (Later, Hubbard ‘discovered’ additional OT levels, including the infamous intergalactic-overlord-heavy OT-3.)

Dianetic auditing, a form of regressive therapy that employs an E-meter to measure physiological responses (as discussed in part one), is the process through which a person becomes free of his or her reactive mind. According to the theory of Dianetics, the mind consists of images based on past experiences that we use to draw conclusions and make decisions about current situations. The images in the reactive mind are called engrams, and they’re seen as the source of maladies from migraine headaches to bad taste in boyfriends. An engram is a term without an easy English equivalent but basically refers to a stored, unconscious image that continues to influence us. These images are typically traumatic or injurious and work something like what most people would call a phobia or simply a bad association. For years I used an example drawn from this book I got for Christmas in 1986 to explain an engram, but given the Church’s decreasing but still intense affection for litigation I’ll make up another drawn from my life.

Let’s say you grew up near the ocean and one warm day you were dangling your feet in the water and saw (or thought you saw — it really doesn’t matter) an eel slither past your toes, and your blood ran cold. You were young when it happened so you don’t really remember it, but for years afterward you’re terrified of any non-transparent water, not just of being in it yourself, but the very idea of it. This is your engram. As you continue to go about your life this basic engram will probably accumulate ‘secondary,’ ‘lock,’ and ‘chain,’ images related to the original engram, for instance your fear of water might keep you from swimming at summer camp, and the teasing you endure from friends will be added to the pain you associate with the basic engram.

In a session, an auditor tries to access, identify, and eliminate the unconscious images stored in the reactive mind. As the E-meter cans feed information about your emotional responses to the auditor (based on the electricity in your body), he will ask you questions, starting, perhaps, with the information collected from your free personality test or perhaps with just a chat about your day. “What did you do yesterday?” he might ask, and as you narrate the day’s events your auditor might note a frenzied movement of the needle as you mention a conversation with your friend Anna and follow up with “what did you talk about with Anna?” As you relate your conversation, the auditor notices movement on the E-meter when you mention a planned stay at a lake cabin and he starts prodding — “have you been to this cabin? Do you like vacations? Do you plan to swim?” You get the idea. On and on this goes until you trace the engram back to its formation, even into past lives, in this way neutralizing it.

This is the fundamental teaching of the Church of Scientology, and most of the people who join the organization to take courses and get auditing find that it works for them, that it makes them feel more confident, capable, and in control. There is another side of the church, of course, the side where if the ‘tech’ doesn’t work for you, if you have problems that Scientology can’t fix, or god forbid you have any criticisms of the way the church operates, you’re punished, ostracized, and made to feel you have no one but yourself to blame (you might even be, like my mother, a ‘suppressive’ person, someone who openly opposes Scientology). But if Scientology didn’t have a core of successful, and often very wealthy, practitioners, it never could have achieved its current prominence or weathered recent storms.

“But what about the aliens?” some people ask. This brings me to the part of the spiel addressed to those with a very cursory understanding of Scientology: ENOUGH ABOUT XENU ALREADY. Never heard of him? Here’s the skinny: in a galaxy far, far away the evil overlord Xenu decided to solve an overpopulation problem by sending millions of aliens to Earth, where they attached themselves to humans as body thetans, creating fear and disease in their hosts and requiring auditing for removal (yes, South Park got it right, almost). But what too few people fail to note when they start with the Xenu talk or fallaciously claim that it’s a pillar of the Church is that the majority of practicing Scientologists don’t know the Xenu story. The Xenu story doesn’t come until the ultra-secret OT 3, which comes well after you’ve gone clear, which requires tens of thousands of dollars of auditing and courses and can take decades. My father, who’s been in the church for nearly 50 years, has never made it past OT 1.

I get deeply frustrated when I hear people say Scientologists must be either nuts or brainwashed because they believe in Xenu. The truth is they either haven’t learned about Xenu yet because they’re too new (or don’t have the financial resources to move up “the bridge to total freedom”) or they have learned about Xenu after many years of training, tens of thousands of dollars spent on courses, and a transformed social and family circle now consisting primarily of other believers who would be forced to disconnect from them should they disavow ‘LRH Tech.’ Some of them swallow their disbelief and get down to the business of eliminating those pesky body thetans who are holding them back. Others simply liken the tale to other rather unbelievable religious stories and say it’s not meant to be taken literally.

When I learned about OT 3 myself at 12 or 13 via a media exposé (this was pre-internet) I innocently approached my father, having difficulty accepting that he could believe such a thing. When he realized what I wanted to ask him about was OT 3 he became visibly nervous and told me he wasn’t ready for that information yet. This was because Scientologists believe that if you are exposed to higher levels of the church before you’re sufficiently prepared, you’ll become physically ill, an awfully convenient way to keep individuals who have not yet committed their lives and their finances to the church from bailing when they hear about the really crazy shit.

Scientology is far from the only religion that holds back esoteric knowledge from all but the most devoted and advanced practitioners. Judaism and Mormonism, for instance, as well as other strains of Christianity, all offer special knowledge only to men of a certain age or to the clergy. The story of Xenu is somewhat like the part of Tibetan Buddhism in which adherents must imagine themselves having [heteronormative] sexual intercourse with a deity to reach enlightenment; for the vast majority of practitioners who never reach the most advanced levels, the existence of those levels is meaningless (or even unknown).

I don’t think it’s fair to criticize a religion on a basis that has nothing to do with how most practitioners experience it. There are plenty of reasons to criticize the church based not on what Scientologists believe, but on how these believers are treated by the organization they’ve given so much to.

NEXT: Leaving the Church.

Stella Forstner is a pseudonym for a Hairpin reader who wishes to protect her family’s anonymity.