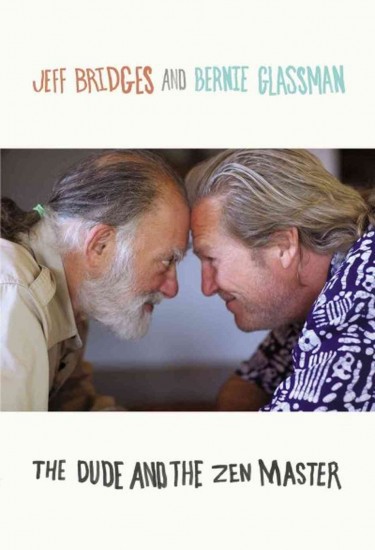

“The Dude and the Zen Master,” Jeff Bridges

In collaboration with his longtime friend and “Zen master,” Bernie Glassman, Jeff Bridges has presented the world with a jam session in book form (Amazon | Indiebound). The scare quotes are not meant to undermine Glassman, who seems like a very nice person with fine, legitimate credentials engaged in the process of doing very nice things in a thoughtful manner, but rather to make clear, from the beginning, that this is the Zen of “….and the Art of Your Chosen Hobby or Pastime,” and not, strictly speaking, Zen-Zen, which is an assumption on my part, as I know nothing about Zen. Western Zen, we’ll say, is what Bridges and Glassman are presenting to us, although perhaps drawing an arbitrary distinction between the two concepts is horribly un-Zen? Jeff Bridges would probably not care either way.

“Book” could also be rendered in scare quotes, as Bridges prefers to think of their creation as a snakeskin. “A snakeskin is something you might find on the side of the road and make something out of — a belt, say, or a hatband. The snake itself heads off doing more snake stuff — getting it on with lady snakes, eating rats, making more snakeskins, et cetera.” You get the idea. This is a book in which sentences are likely to end with “…right?” A book in which koans appear chiefly in pun form as “The Koan Brothers,” and the question of how a rug could really tie a room together is paramount. It is a book for stoners, a book for Parrotheads, a book for people grooving uncomfortably into middle age, and a book for people who just happen to like Jeff Bridges. Most people, in other words, and people who are unlikely to take it more seriously than they should. The Dude abides, right?

Broken down into a series of dialogues between Bridges and Glassman, “The Dude and the Zen Master” is an exercise in likability. Bridges, a man so exceptionally amiable as to beggar the imagination, is in rare form here. What could be objected to? His chosen philanthropic undertaking? Child hunger. His wife? Long-suffering and beloved. His weakness? Cigars. “The body is the temple, so you should offer it some incense.” Bridges never forgets to thank the crew, even when he’s not on a movie set, a charm which approaches but does not quite reach the zone of self-parody. It is no coincidence that the crisis of “The Big Lebowski” involved a mistaken identity. To know the Dude (and, by extension, Bridges’ own meditational endgame) is to love him. Once the self has been sufficiently effaced, there’s no edge left to dislike or object to.

And that, ultimately, is what we are dealing with. The cheerful annihilation of the self, not necessarily as a spiritual exercise, but as a different way of being a celebrity. Does that make Bridges’ book and persona a schtick? Not necessarily — if anything, the man seems overly authentic on the page and in the flesh. Rather, Dude-fashion, we are watching a religious tradition stripped of its aggravating difficulties and demands and left with a thoroughly unobjectionable kernel: you do you. Or, as Glassman puts it, “you just do.”

For Bridges, just doing can mean a few things. It can mean making tiny clay heads to give to his loved ones, or turning a ridiculous fight with his hair and makeup guy into an opportunity to admit he’s heavily invested in his own self-image as a chill-to-a-fault Dudester. On the set, he claims, he transcends his own abilities by turning the project over completely to the director. Barring, of course, any revelations that seem to come to him “from a higher power.”

Glassman’s role, it would seem, is both to rein Bridges back in and to attempt to elevate the discourse back onto the plane of the spiritual. While Bridges riffs on his own shortcomings and foibles and all-around goofiness, Glassman is more likely to pop in and remind him of the danger of expectations, of prioritizing the “final outcome,” a downfall which Bridges, to be fair, does not seem to be in imminent danger of. The life of Jeff Bridges (a subject one expects his editor begged him to include in at least some detail) is explored in bits and pieces; a tribute to Sidney Lumet, the joys of improvising with Martin Landau, childhood dance lessons, the surprising wit of Kevin Bacon, resisting following his father into the profession, his band, meeting his wife and finding himself horrified that he would have to get married, losing his parents, being the Dude. Abiding.

Glassman approaches Bridges’ degree of adorability at times, although, without having a mental image of a slouchy-sweatered Dude gesticulating with a White Russian, he has to work a little harder to do so. Or, rather, he works lightly and expends his energies on intentional simplicity. His central metaphors include both “row, row, row your boat,” “The Wizard of Oz,” and the wisdom of Robin Williams’ Mork. When he claims to always carry a red nose in his pocket (for the purpose of diffusing “serious” conversations), one can’t quite decide if the correct reaction is to emulate his attitude or say: “Jeez, guy, you’re Patch Adams now?” Upon learning that his time in clowning (trainer’s name: Mr. YooWho) led him to work with “Clowns Without Borders,” an organization which works primarily with small children in refugee camps, the second reaction seems exceptionally un-Bridges. The Real Bridges: “Clownsville, man.”

Various critiques of relentless likability — a natural development of a culture which enjoys nothing so much as clicking small thumbs-up buttons next to blog comments and images of cats wearing hats and reminiscences of 1990s pop culture — have been attempting to gain a foothold this past year. That they have largely fizzled out is unsurprising. What’s the alternative? The mutual admiration society of “The Dude and the Zen Master” may be a little pop-y and a little vacant, but in the world of celebrity memoirs, it’s practically “The Education of Henry Adams.”

Admiration, in general, drips from these pages. Bridges likes people who are good at things, or at least better than him, and he likes to give them their honorifics accordingly. Glassman, as previously established, is a Zen master (without even coaching the Lakers!) The Coen brothers hired a “master bowler” to whip him and his costars into shape for “Lebowski.” It’s not just Bridges, of course. At the gym the other day, I was presented with a coupon for a free spray tan session with a “master technician.” (Picture the multi-year apprenticeship involved! No doubt said master was pledged to the spray tan guild as a young child, laboring ceaselessly at the throttle under the watchful eye of his own master, and so on back through the ages.) Bridges’ “master bowler,” accordingly, is inserted into the text to undermine the very idea of theory. Having been brought to his knees by an attempt to use “Zen and the Art of Archery” to further his craft, you say, the bowler had to go back to basics. “I just throw the fucking ball! I don’t think.” Bridges: “I dug that.”

“The Dude and the Zen Master,” for the most part, does not want to encourage you to complicate either your life or your spirituality. Concrete advice is at a minimum, and would probably seem helplessly vacant and obvious were the tidbits not pleasantly sandwiched between Bridges’ charm and Glassman’s anecdotes: “Do the best you can and don’t take it so seriously.” “Look in the mirror, and laugh at yourself.” “Keep on trucking.” “Everyone you meet is your guru.” Like many popular approaches to the self, and reasonably useful ones, at that, “The Dude and the Zen Master” wants you to figure out you’re already in the other place you want to be. What’s not to like?