Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Many Faces of Barbara Stanwyck

by Anne Helen Petersen

Maybe you’ve never heard of Barbara Stanwyck. She certainly isn’t the first star that comes to mind when you think of classic Hollywood. Ask for a screwballer and I’ll say Katharine Hepburn; ask for a drama queen and I’ll give you Bette Davis. Other stars had more active love lives, more stunning faces, more Oscars, more drama. But then ask me for my favorite films, and Stanwyck’s all over the place, lilting into scenes, making me fall off my chair laughing and/or crying, riding “all the way down the line” in, let’s just be honest here, the best film noir that isn’t Sunset Boulevard. She averaged five films a year, playing the tomboy, the burlesque dancer, and the good girl with equal skill. She was everywhere and everything in the very best of ways.

Stanwyck wasn’t as stunning as Lana Turner or as piquant as Hepburn, but she was the so-called best actress never to win an Academy Award, despite being nominated a billion times. In her best films, she eats the role for breakfast. She’s delicious to watch, and, much like Hepburn or Rosalind Russell, made me realize that there was a time when being smart and sexy onscreen weren’t mutually exclusive. More than any star I’ve written about, her magic was in her films, not her fan magazine spreads or the way people talked about her. Which isn’t to say she didn’t take a damn good glamour shot — I mean look at this awkward diving board pose! — but that the source of her charisma was so heavily textual, rather than extratextual. I believe we call that acting.

Stanwyck was born Ruby Catherine Stevens and spent her early years in Brooklyn. But at age four, a drunk pushed her mother off a streetcar, killing her, and two weeks her dad fled to work on the Panama Canal, leaving Stanwyck and her siblings as orphans. Her older sister — but only slightly older — took care of them at first before they headed to a series of foster homes, from which Stanwyck regularly ran away. At some point, she was released back into the custody of her older sister, by then a showgirl, and Ruby toured with her, learning the routines and becoming enamored with the lifestyle. She dropped out of school at age 14, took an assortment of shopgirl jobs, and, in 1923, at the age of 16, landed a semi-permanent gig as a showgirl with Ziegfeld Follies.

Just so deliciously gorgeous. She worked the midnight to 7 a.m. shift; she apparently taught dance lessons at a gay and lesbian speakeasy? She was, in other words, awesome. Next she found her way to Broadway and was cast in Burlesque (1926) for her “rough poignancy.” It was a huge hit, which led to her first bit role as a dancer in Broadway Nights (1927) for First National. But she couldn’t be Ruby Stevens — the producers thought it sounded, well, too burlesque. And so she became Barbara Stanwyck: smooth off the tongue, with a bite at the end.

Stanwyck had an awesome, deep voice, and her new husband, Frank Fay, whom she’d met while making Burlesque, moved with her to Hollywood and helped make her some sweet deals, working between Warner Bros. and Columbia without ever having to sign a long-term deal with either. She made some shimmery Capra films and worked steadily — even if none of her films were particularly memorable, she did get to look like this in Forbidden:

She was, as they say, a “hard-boiled girl of easy virtue,” which is another way of saying that she was smart and had a good time, and that I would want to be her friend. She also bore the brunt of The Hays Office’s decision to finally tamp down on “Pre-Code” films, a.k.a. films that flaunted the existing censorship guidelines. In the original script for Baby Face (1933), she plays a girl from the wrong side of the tracks, stuck in a steel town, exploited by her bootlegger father. She takes up some Nietzschean philosophy and decides to use the big city and big money guys to get what she wants — just like Nietzsche would say she should. So she gets a job at a bank and uses her “feminine wiles,” if you’re picking up what I’m putting down, to make her way up the food chain, seducing one executive after another, before making her way to one who was very engaged … to a big exec’s daughter. And then Daddy Big Exec falls for her, puts her up in a love palace, and gets her a MAID, before original fianced executive finds her there and SHOOTS BIG EXEC AND HIMSELF. Amazing. Just amazing. The new head of the company banishes her to Paris, but she works her magic there as well — and when the new head comes to visit, HE FALLS FOR HER TOO. Barbara!

The bank fails, the new husband is blamed, Barbara refuses to return all her fancy-pants stuff to save the bank and flees to Europe, triumphant. Husband shoots himself, the end. Man-eater in-fucking-deed.

And so the film would have ended, but The Hays Office had other plans. Baby Face was one in a series of “kept-women” films, including Possessed (Joan Crawford) and Red-Headed Woman (Jean Harlow) that a) featured women using sex to get what they wanted, and b) had proven enormously popular. Red-Headed Woman was such a sensation that Joseph Breen, the “enforcer” at the Hays Office, feared that all the other studios would try to top it by making their female stars even more manipulative and destructive, and end up in even more luxury and bliss.

Baby Face did just that — and while most of these kept-women films had taken place at the department store, this one took place at the bank. The year was 1932. Stanwyck caused the fall of the bank. In other words, women like Stanwyck were responsible for THE ENTIRE DEPRESSION.

The Hays Office thus suggested a major revision: When Stanwyck leaves the new husband and makes her way to Europe, she has to realize that she actually loves him — is, herself, a victim of love — and would give back all of her goods in order to be with the man she loves. The revision should, according to official correspondence…

“…indicate that in losing Trenholm [final boyfriend] she not only loses the one person whom she now loves, but that her money also will be lost. That is, if Lily [Stanwyck] is shown at the end to be no better off than she was when she left the steel town, you may lessen the chances of drastic censorship action, by thus strengthening the moral value of the story.”

Fox continued with production, and may or may not have taken all of the advice to heart. But in the intervening months, a confluence of events changed the way that censorship would function in Hollywood. [If you’ve heard the Hays Code/Censorship Lecture before, either in one of my previous columns or in RTF 314 Fall/Spring 2009/2010, feel free to skip ahead.]

To be reductive, up to that point, there had been rules about what films could show and imply onscreen — 11 Don’ts and 25 Be Carefuls — but Hollywood had effectively ignored them. They became increasingly flagrant in their flouting, as evidenced by the success of Red-Headed Woman, a slew of gangster films, Tod Browning’s infamous Freaks, and Mae West’s beautifully subversive She Done Him Wrong.

At the same time, Hollywood was in financial peril. Roosevelt had just been elected. The individual censorship boards at the state and local level were threatening to collaborate with the national government to put the industry in what they believed to be its place — with the support of the Catholic League of Decency and some of the leading (and most prudish) fan magazine editors. The studios, in other words, were over a barrel. So they agreed to allow the Hays Board to “enforce” the Production Code, and from that point forward — until the Code itself began to disintegrate, for various economic and cultural reasons, in the 1950s — it would have the final say on what would and would not be given the “Seal of Approval.” And without a Seal of Approval, a film simply did not get distribution. To be clear, the studios were not censored by the government. Rather, they censored themselves, lest they lose their audience. And indeed, that’s how the most insidious censorship actually works — with the willing cooperation of the cultural producers themselves.

Back at the end of Baby Face: Stanwyck now comes back from Europe all sorts of repentent, finds that her husband has shot himself, but OH WAIT it’s not fatal, she comes to his bedside, where he awakes to her smiling, supplicating face. She is, we are to believe, a changed woman, and from this point forward will stop causing financial crises. The kept-woman cycle was effectively over.

Which isn’t to say that Stanwyck wasn’t still playing slight variations on the same kind of woman. They just always fell in love at the end instead of causing deaths and financial ruin. She plays an “honest gambler” in Gambling Lady, and a stable hand who makes everyone fall in love with her in The Lady in Red before switching to a loose agreement with RKO that allows her to freelance at will.

Stanwyck was also in the process of separating from her husband, who had initially been all sorts of helpful when they first moved to Hollywood, making deals and opening doors. Yet after Stanwyck’s fortunes rose and his fell, husband began to wallow in despair, throwing her around and getting wasted. In other words, he turned into the male lead in A Star Is Born — a narrative long-rumored to be based on their lives. The two divorced at the end of 1935, with Stanwyck gaining custody of their adopted son.

A series of lackluster films followed — I mean, all right all right, I’d watch her as Annie Oakley all day, but the rest of them are just okay — but lady worked. Between 1934 and 1937 she made 15 films, including the saddest film to end all sad films, the grandmother of all weepies, the movie that will dehydrate you in one sitting…

… STELLA DALLAS.

Stanwyck is Stella, a social climber in a relatively loveless marriage to a formerly wealthy man. As she ages, she makes the classic decision that if she can’t find happiness in the upper classes, then perhaps her daughter could in her stead. Because the daughter is of “high stock,” she’s naturally able to snag all sorts of young rich hotties, but her mom is there to be gauche and embarrassing and get in her way.

Complex plot twist leads to complex plot twist leads to Stella self-sacrificing the shit out of herself for her daughter’s happiness, culminating in this killer shot:

I mean, I realize I made it sound like a Hallmark movie, but just remember that there always has been and always will be a fine line between film melodrama and Hallmark movies, and that fine line is the presence of BARBARA STANWYCK. The plot is ridiculous. The way it valorizes self-sacrifice is ridiculous. But if you’ve ever been embarrassed by your mom, ever wanted to dispose parts of yourself/your past in order to get a guy, ever just wanted to live with the normal people up the street — this movie will speak to you. And then it will make you collapse in a pool of your own tears.

And what I love about Stella Dallas is how it fits within the Stanwyck pantheon: it’s a melodrama-fest, and she’s great and dramatic and winning all the awards, but then you can watch The Lady Eve and Ball of Fire, both from ’41, and realize what an immaculate comedienne she is.

But The Lady Eve! You guys you guys you guys you guys Henry Fonda is an ophiodiologist. A snake expert. Who just happens to also be the heir to an enormous fortune. He finds himself on a cruise ship with Stanwyck, the perfect con-woman, and her partner-in-crime, also known as her father. I always think of Henry Fonda as a self-serious stick in the mud, Tom Joad etc. etc., but then I remember that he’s actually the perfect straight man for others’ humor: just watch him get silently teased in My Darling Clementine, or play the bookish scientist who gets the hiccups and doesn’t realize Stanwyck’s trying to seduce him.

This clip is two kinds of perfect: Stanwyck talking fast watching Fonda thinking slow.

And just when you thought 1941 couldn’t get any better, she stars opposite Gary Cooper TWICE: chewing some Capra-corn in Meet John Doe and sizzling off the screen in Ball of Fire. Gary Cooper! BACHELOR PROFESSORS! “Yum yums,” glitter costumes, sausage-roll bangs, and legs, legs, legs. It’s a classic Howards Hawks screwball; let’s take the day off and watch it all day.

At this point, Stanwyck had become the highest paid woman in America. “Barbara” was the third most popular baby name in America — almost entirely because of Stanwyck (if you’re wondering why so many moms are called Barbara, blame Stanwyck).

Up to this point, Stanwyck had played the seductive girl, the amiable girl, the Western girl, the screwball girl, and the self-sacrificing girl — but never the truly evil girl. When approached for Double Indemnity, she thought it might wreak havoc with her image, as her character was, to quote the script, “rotten to the core.” The plot, based on James Cain’s serialized novel, called for Stanwyck and her co-star to kill off her husband for the insurance money — and then for Stanwyck to pull a double-cross on her co-star. There was pre-mediation, lots of bared leg, insinuations of sex, but, according to Code rules, “comeuppance” for both at the end. Which is all to say it was not very Stanwyck. But Billy Wilder, crafty director that he is, asked the hesitant Stanwyck, “Well, are you a mouse or an actress?” Stanwyck took the part, and the rest is noir history:

Indemnity, like The Lady Eve, is streaming on Netflix, and both are right around 90 minutes, which is basically the perfect amount of time to drink a double Gin & Tonic, so you really have no excuse not to spend the next two nights revelling in the contrast. I rewatched it the other night and spent most of the time thinking about a) how much Fred MacMurray looks like my Granddad from that time and b) how horrible Stanwyck’s wig is but that I maybe sorta want it?

If you don’t know what film noir is, well, you actually do. Film noir is L.A. Confidential, is Memento, is Looper, is Brick. Noir wasn’t noir at the time — it was the French, looking back and being all categorical and periodizing, who gave it that name. At the time, it was just what happened when the gangster film became less popular and the murder mystery rose in its place — oftentimes based on the “hard boiled” fiction (clipped, terse dialogue and plotting) that was percolating at the time. Noir looks at the sullied underbelly: the evil, the darkness beneath the shiny exterior. It plays with shadows and slanting light, smoke and slatted blinds. Double Indemnity — and its startling success — set the tone; Sunset Boulevard, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Gilda, and dozens more made the genre. Chinatown made it color; Twin Peaks and Veronica Mars made it television. If I had to teach one type of film forevermore, it’d be noir, no question: the psychology, the aesthetics, the powerful, enrapturing women — those femme fatales always died, but I never remember that part, just the slinking seduction.

And MacMurray and Stanwyck grating off each other — it’s a revelation. When I first watched this film, I was firm in my belief that MacMurray was exclusively the dad in My Three Sons, which I watched the shit out of on Nick at Nite. In truth, he was the highest paid actor in Hollywood and fiercely popular — so much less Dad in this movie — with a convincing weakness for the way Stanwyck’s anklet pressed into the flesh of her calf. As for Stanwyck, even the bad wig — selected to highlight her character’s duplicity and trashiness — can’t take away from the slink of her voice. I’d do anything she told me to.

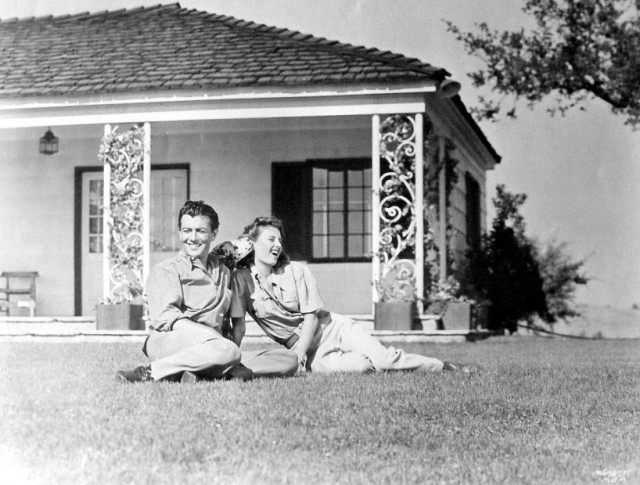

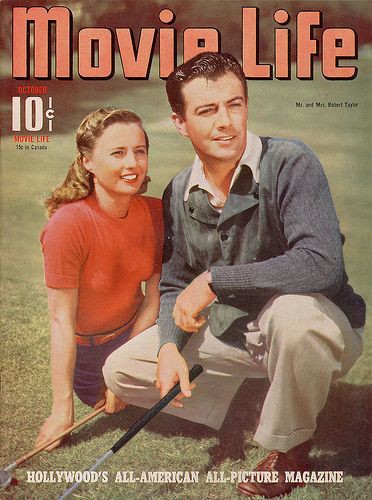

Perhaps, at this point, you’ve realized that I’m basically just talking about how awesome Stanywck is in all her movies, and that she spent all day changing costumes and learning lines. It’s not entirely true. After her divorce was finalized in late 1935, she began filming This is My Affair with Robert Taylor, “The Man With the Perfect Profile,” then a rising star with MGM. Stanwyck was hesitant to get serious so soon after the demise of her last horrible marriage, so they flirted and totally didn’t sleep with each other for three years, until MGM finally pushed them to wed in 1939. Their courtship and marriage, if pictures are to be believed, was characterized by a lot of sport, SoCal ranch living, and natty outfits.

They were a perfect match, and not just because they could rock matching equestrian outfits. Their politics were also the same, which is to say archly conservative. Stanwyck loved her some Ayn Rand — enough to push Warner Bros. to buy the rights to The Fountainhead. She was besties with John Wayne, Gary Cooper, William Holden, Bob Hope, and Fred McMurray — the good ol’ boys club of conservative Hollywood. Taylor helped form the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals in 1944 with the explicit purpose of red-mongering and extracting Communist influence from Hollywood; as their official mission statement explained, “in our special field of motion pictures, we resent the growing impression that this industry is made of, and dominated by, Communists, radicals, and crackpots.”

In 1947, Taylor was a “friendly witness” before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which meant he named names of supposed undercover Communists and contributed to the formation of the blacklist. Dude kinda sucked — not because he was conservative, really, but because he was a red-mongerer. The Hollywood Ten weren’t Commies in the Russian-fear-mongering sort of way; they were Commies in the 1930s-Let’s-Make-the-World-Awesome-For-Everyone sort of way.

So Stanwyck was a Republican. An extremely skilled actress with a seemingly boring home life, with an image characterized by dexterity, intelligence, and monogamy. She’s like the conservative Meryl Streep: When I think of both women, I don’t think of their lives, I think of their roles. I realize you could say the same for many actresses, especially if you’re not a Ph.D. in celebrity gossip, but with most stars, their personal lives and what you know of them shapes how you think of their roles. When you say “Jennifer Aniston,” I don’t think of Horrible Bosses; I think of Brad Pitt and never finding love with a subtle waft of Rachel from Friends. Which isn’t to say that Stanwyck wasn’t a star — she was, after all, still obligated to pose for publicity glamour shots like this one…

…much in the same way that Streep sits for an interview and photoshoot with Vanity Fair to promote an upcoming film. What I’m trying to suggest is that unlike Flynn or Gable, unlike Cooper or Bogart, unlike Crawford or Davis, Stanwyck didn’t just have a gloss of morality and propriety. She was seemingly nice to everyone. Film crews adored her. Frank Capra claimed that “in a Hollywood popularity contest she would win first prize hands down.” She was ASB President and Valedictorian and head of the Glee Club and dating the guy with the most perfect profile in Hollywood — and if it weren’t for all those blissful, totally beguiling performances, there’s no way I’d spend 4,000 words on her.

Or, at the very least, on the first two acts of her life. The third act, though, WOWZA, let’s go:

In the years following the end of World War II, the old guard of Hollywood stars were under threat, from television, from diminishing audiences, from sexy new teen idols who appealed to the increasingly important youth audience. The aging male stars could still hang — just like today — but the female stars were gradually banished to roles as washed up stars (All About Eve) or slightly deranged single women (everything with Joan Crawford post-Mildred Pierce; helllllo, Lana Turner).

Stanwyck thus said good-bye, screwball heroines, hello, melodramatic, fiercely independent slightly aging ladies:

Keeping her bangs intact in The Furies (1950)…

Hot middle-aged make-out with Gary Cooper in Blowing Wild (1954)…

As the Maverick Queen (1957).

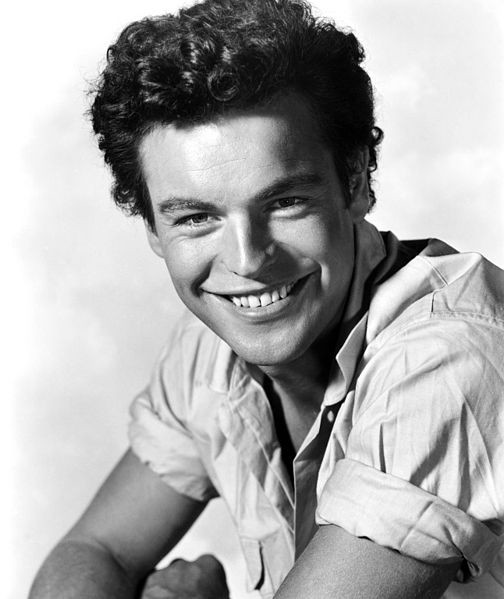

And love life bonus round: she and Taylor amicably divorced in 1950, and while filming Titanic, she hooked up with a young, newly minted star named Robert Wagner. He was 22, she was 44, and best of all, she was playing the mother of the girl his character courts in the film. But who can resist the Stanwyck?

Here’s what Wagner looked like around this time:

‘Pinner please. You would tap that. Their relationship lasted four years, so D.L. that you can’t find a picture of them together apart from a publicity still from Titantic. Stanwyck eventually ended things, leaving Wagner to go play with childish things like Natalie Wood, with whom he made out for the fan magazines.

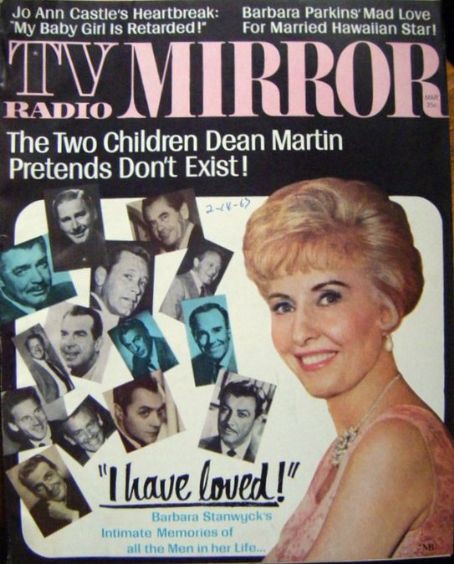

What was a newly single woman with a 30-year career do? You read yourself some Ayn Rand. You star in your own television show like a boss. You do a couple of not-horrible films. You offer intimate memories of the huge shoebox of all the handsome men you’ve made out with, in and out of character.

You do charity work. You become Tori Spelling’s godmother. You star, at the age of 76, in the Thorn Birds. You appear in 85 films over your 82 years. You are the embodiment of enduring class: never flashy, always working. Never salacious, always watchable. Tough yet vulnerable, luxurious yet restrained.

Am I just thinking of Stanwyck circa 1944? Maybe? Probably. But that’s what every generation does with its classic stars: we turn them into their best, most evocative selves. It’s the selective editing of history and memory, the quiltwork of stories my granddad told me, of fan magazines that smell like smoke instead of fresh paper, of films streamed, not projected.

Something is lost, of course. But with the benefit of the wide lens of hindsight, we’re able to see the type of womanhood and female stardom Stanwyck embodied: She was less abrasive than Hepburn, less fragile than Turner. She had her shit together, and even if women’s lib didn’t turn her into a feminist, I can still read her characters that way — the same way you can read Cary Grant’s characters, or any other characters, for that matter, as queer. That’s our privilege as audiences: It doesn’t matter what she thought she was, or even what the studio framed her as, so much as what we do with her in our own minds. It’s all about subjectivity and the stories we tell ourselves. Stars become meaningful only when we allow them to.

Film critic David Thomson called Stanwyck “delectable, a stirring mixture of toughness and sentiment, a truly and creatively two-faced woman.” He was speaking, of course, of her ability to play both Stella Dallas and The Lady Eve, both a “ball of fire” and a murderess. But the conceit extends to her private life as well. Stanwyck never had a truly unique star image, a major scandal, or one thing that she meant to all audiences. Was she a man-eater or a homebody? A woman secretly dating a man half her age or an ardent conservative? Or all these things and more? I look at subtle allure of her face below, the tension between innocence and ruin, and realize that she can be whatever I — or you — need her to be.

Previously: In Like Errol Flynn

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.