Remembering Lilith: Tracy Chapman

by Anne Helen Petersen and Simone Eastman

The first in a series on Lilith Fair artists and their evocative all-consuming everlasting meaning to our adult selves.

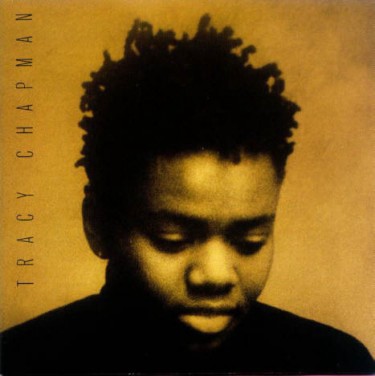

AHP: The first time I heard Tracy Chapman I was in grade school. My mom was playing her CD on the massive boom box we kept in the kitchen to facilitate family dance parties. I couldn’t decide if I loved these songs or if they were just making me feel something, but I was positive they were sung by a boy. My mom showed me the CD cover. My 9-year-old self was still unsure.

SE: Your mom was kind of hip, because MY mom, when she found a Tracy Chapman CD on my bedroom floor when I was fourteen, looked at the cover, sneered, and said, “No wonder you’re suicidal if you’ve been listening to this shit!” (And by “kind of hip” I think I mean “capable of giving healthy love”?)

But also, my mom was the implicated first time I heard Tracy Chapman, too. (Remembrance of Things Past reverie ahead!) So I was 14 years old when I first heard “Fast Car” in my friend Christina’s . . . car (haHAAAA!). It was probably summer, August-muggy. She was 18, had graduated, was about to go to college. She was my best friend. My only friend, really. In that high school way we mostly did nothing — watched South Park, invented weird projects for ourselves, read time-travel Viking romances next to the pool at her dad’s condo, drove around a lot.

What I remember most clearly is how cinematic and true the song felt to me. I grew up in a semi-rural suburb outside a small Rust Belt city, and when she drove me home the road would get darker and darker, fewer street lights, more space between the houses. By the time she took me home every evening we’d have been together for hours and run out of things to say. So we’d listen to music, loud, and the car would cut through the dark. There were all these sort of gentle rollers that we would accelerate and crest, and then our stomachs would drop, and I remember this one spot in particular where all of a sudden this field on the corner of my road would come into view. If we were lucky it would be all lit up by lightning bugs.

And if we were really lucky — or if I was, at least; I have no idea whether this was how Christina heard it — the field would drop into view as Tracy was singing, “City lights lay out before us

And your arm felt nice wrapped round my shoulder

And I — I had a feeling that I belonged

And I — I had a feeling I could be someone, be someone, be someone.”

Which. We do so much translating with the things we love, the art we love! My life was staunchly suburban and these were not city lights and it would be years and years until someone’s arm felt nice wrapped around my shoulder. But even then I knew a lot about escape, about wanting to, and about how rare and special it was for me to feel connected and hopeful, like there was some possibility of a different kind of life.

And then it would be over and I would get out of the car into the wet, hot night and watch the headlights sweep down the driveway, something that filled me with sadness, and start counting the hours until she came back.

AHP: I came late to Fast Car obsession — although when I did return to it, I already knew all the words, like it had imprinted in my pre-feminist mind for when I needed it later. But the beat of that song! There’s a reason why so much of Chapman’s stuff has stayed on the feminist fringe and that song went mainstream, where people could listen to and feel its sadness without thinking too deeply about the tragic social reality at its core.

SE: THE TRAGIC SOCIAL REALITY AT ITS CORE!!!! is why I actually think my mom hated Tracy Chapman so much. It took me another decade to understand that Tracy Chapman was actually SINGING HER SONG. The escape from the fucked up home, the hope that a man could actually rescue her, the plans that evaporate as life grinds you down, and maybe even (though probably not) the weary willingness to free someone else from the weight of it. So I can see why a lady might not be Into the Top 40 expression of her own tragic life. On the other hand, my mom was also a pretty racist homophobe, so that may have also been part of her issue. But “Fast Car” was not your gateway drug?

AHP: I know, right? But my first deep obsession with Tracy arrived the summer between freshman and sophomore year of high school, when I feeling very important as an official junior camp counselor. On the last night of each session, we were allowed to stay up as late as we wanted with all the other junior camp counselors, which was basically an invitation to sit on the porch of the lodge and flirt until the sun rose. One of the senior counselors, a woman with a nose ring and short, flippy hair, a woman so ineffably cool she must’ve been in her early twenties, put on New Beginning. She left and went to sleep like a non-15-year-old, but we stayed and the CD went on repeat.

When you’re 15 and in camp love with the boy beside you and it’s 3 a.m., “The Promise” takes on entirely new meaning. There’s such a delicacy and warmth to this song — a quiet ache and tenderness. I want to fall asleep in the arms of this song.

SE: The best comment on that video is “A 23 years old man is crying now.”

Which also raises an interesting line of thought about Tracy Chapman’s gender presentation. Like: you remember hearing her voice and not being sure whether it was a woman or a man. And a) that kind of makes me think of the first time I heard Nina Simone, b) I wonder if it creates some play in terms of the audience she attracts — like if that ambiguity becomes a kind of screen that listeners of all genders and sexualities can project themselves onto? (Did I just get too Gender Studies?)

AHP: Lady, you can never get “too” gender studies! Gender Studies IS LIFE! I do think that the rich ambiguity of her voice is part of her appeal to a broad swath of women … but dudes? Even my most feminist of (hetero) dude friends resisted The Chapman.

SE: I . . . spent ten years in same-sex educational environments, so I don’t have a temperature check on how The Chapman translates for bros. Here, I did some research:

AHP: Shit, I wish Google was that on point when I ask it to locate “jobs where I get to write about hot old movie stars all day.”

SE: Well, I also consulted with my Facebook Bros. What, you don’t have Facebook Bros? Anyway, my informal polling suggests that YES, some dudes do listen to The Chapman, but most of them are bros who are in some way non-normative: not white, not straight, not American. Which is not to say that there are not also some very soulful straight white American men who love The Chapman. But I’d guess that for them, being moved by her words is a private pleasure. To them I say, “You must come out . . break down the myths, destroy the lies and distortions. For your sake. For their sake.” FOR TRACY’S SAKE. (Was that tacky? Quoting Harvey Milk like that?)

AHP: Here’s the thing: most of the other mainstream Lilith Ladies were putting their feminist thoughts in code. Sarah McLachlan sings entirely in riddle, and Natalie Merchant takes on the personas of every character in American Horror Story plus fairies. You might sense the feminism, anguish, and injustice, but you can also readily ignore it. But you can’t listen to a song like “Behind the Wall” and not feel indicted for patriarchy’s collective sins.

SE: I mean, I think Tracy Chapman is actually a good example of this. Because the best-known cut is, of course, “Fast Car,” which is a story about class and poverty that lets you ignore class and poverty. But what song actually leads the album? “Talking ‘Bout a Revolution.” In which she straight up says, “Poor people gonna rise up/And get their share.”

Or “Across the Lines,” a song explicitly about race, white supremacy, and violence.

I am the first to acknowledge that we pick and choose what we want from art, and that in many ways that’s more than okay. But then I think about TC’s white fans (including me!) skipping over every track that calls us to account for ourselves or any song that asks us to see and feel difference and discomfort, rather than identification. Like, how many of the 10 million people who bought Tracy Chapman listened to anything other than “Fast Car”? I mean, do I necessarily think “Across the Lines” is as lyrically powerful a song as “Fast Car” or “Talking ‘Bout a Revolution”? No. It’s a little preachy. But it feels lazy, and a function of privilege, to say that the most popular of her songs are the least political because they’re just “better songs.” And I think noticing this matters, because I think we (the cultural we, the Music Industrial Complex we, and the white people we) really deny race and racial identity a place in contemporary folk-rock. We select for the stuff that’s the most “white,” and whiteness is endemic to Lilith Fair’s brand, even though the roster of Lilith performers was pretty diverse; TC, India.Arie, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliott, Queen Latifah, Des’ree, Me’shell Ndegeocello, Mýa, Joanelle Romero, Deborah Cox, and Monica all played the Lilith main stage in the festival’s three-year ’90s incarnation (we do not talk about 2010). But when we think of “Lilith Fair musicians,” we mostly think of white women and of songs about feeeeeelings that aren’t too political or do that dog-whistle thing. I don’t know. I’m trying to sort this out. (I am never not trying to sort out my whiteness.)

AHP: Oh total truth. Take the case of Britain’s Got Talent Michael Collings: here’s a young, working class, very white guy who lives in a “caravan” (read: trailer) with his parents, with a young fiancee and an unplanned baby on the way. He covers “Fast Car” and brings down the house and the video gets so popular it almost breaks YouTube.

Collings is able to ventriloquize the message of the song because of his class — but can you imagine if a black Brit got on stage and sang “Talkin’ About a Revolution?” I want to watch those two too-clever host dudes respond to THAT.

SE: Let us turn now to the Later Chapman. Like what about “Give Me One Reason”? The Tracy Chapman song that sounds nothing like “a Tracy Chapman song”?

AHP: That song used to always be on the Adult Contemporary station where I grew up, and I wanted go over to the station and force them “At This Point in My Life” followed by five minutes of dead air.

At some point in high school I became obsessed with all Lilith-y artists, a point we’ll address over the next few weeks/months/lifetimes, but Tracy was always there…

SE: TRACY WAS ALWAYS THERE!

AHP: …even when I was spending a lot of time listening to Fiona Apple with the lights off.

SE: I did that, too. The Fiona with the lights off thing. Did we all do this? Once while I was literally lying on the floor. Then my roommate came in. Oops.

AHP: Freshman year of college, Telling Stories came out and immediately became a litmus test of friendship. My roommate and I eventually got to the point where we couldn’t start our homework without putting it on. It was the first CD on every road trip back to Seattle — the perfect steadiness bringing us over the mountains. The album really bleeds into itself: I don’t think of any songs in the singular, but the album as a whole, as an experience, as an emotion. A bygone era?

SE: This is an intense fucking album. It’s all breakup and heartbreak and personal failure and deception and self-deception. And I also notice that, compared to Tracy Chapman, this album is way, way, way, way, way less overtly political. Much more internal. “First Try” is haunting and spare.

(The video for the title track is kind of delightfully weird and involves a lot of TC sway-dancing. Get it, girl.)

AHP: And then Let It Rain, an album so underappreciated — it has this ghostly quality to it, plus Chapman is rocking a boss pea coat on the cover.

Plus I love that whoever uploaded “In the Dark” to YouTube just puts the song in a black background. Literally IN THE DARK, kids.

SE: Like our spirits, Anne Helen Petersen. In the dark like our spirits. My Tracy Chapman jam, though, is from the 2005 album Where You Live. Which, full disclosure, I only recently discovered while I was at a coffee shop that was playing the XM satellite station “Coffee House” (haHAAAAAA!).

Like, seriously, this shit fucking kills me. (Hilarious inexplicable comment: “Hang in there Greece. Your star shall shine again.”) Not to get super-real with you, but every single time I hear “if you knew that you would find a truth that brings a pain that can’t be soothed, would you change?” it just kills me. I mean, Tracy Chapman is SINCERE. Sin-cere. This is a song about how hard it is to want to become a better person. There is no snark. There is no irony. In 2013 I can hardly look at myself in the mirror, let alone get through the day, without those things. And yet. In the same way that “Fast Car” was a doorway to imagining the future when I was fourteen years old, I’m a thirty-something lady with, like, a dozen years of therapy under her belt (ahh can’t wait till we talk about how Dar Williams influenced our feelings about therapy) and this goddamned song makes me want to keep trying. One of the things I love most about it is that the chorus starts like this: “How bad, how good does it need to get?” How bad do things have to get — or how good do they have to get? This is not just a song about finding yourself in a low, dark place! It’s also about those moments when we find we want to become worthy of the lives we already have. Poetry. POETRY!

AHP: And you know who else loves that song? THE HBO QUALITY TELEVISION PREVIEW REEL, THAT’S WHO.

Tony Soprano, would you change? Jimmy McNulty, would you change? Al Swearengen, would you change? ENTOURAGE BROS, IF YOU SAW THE FACE OF GOD AND LOVE, WOULD YOU FUCKING CHANGE?

SE: That is the realest fucking thing I have ever seen.

AHP: That’s how I feel about every song on every album: like she makes me want to live a real and valid life. Many of the other ladies we’re going to talk about — Dar, Fiona, Our Lady of Ladies McLachlan, Weird Mystical Aunt Natalie Merchant — made me feel all the feelings, but Chapman has always had this quality that makes me feel serene yet also like I must go out and do some social justicing right now. It’s that crazy mix of feminist agit-prop and soul soothing that alienates while also making itself amenable to satellite radio.

SE: I don’t want to tell you how profoundly satellite radio has influenced my life though I don’t even own a car. And I think you’re exactly right about that edge she has. Because Dar Williams wrote a song called “The Poignant Yet Pointless Crisis of a Co-Ed.” There is nothing pointless about a poignant Tracy Chapman song.

AHP: Someone on Twitter just pointed out that Chapman hasn’t released an album in five years — and brought up a question I circle back to every month or so with people whose art has been a significant part of my life: Where is she? Is she okay? I have to believe she is: I feel like she’s made a home for herself somewhere with crisp, clean air, somewhere where you wake up in the morning and sun’s filtering in the window, then you read the paper with a steaming cup of tea and set about your meditative, richly pleasing day. If she has a partner, they do a lot of reading and gardening and cherishing of each other; if she doesn’t, she nevertheless feels whole. Am I projecting? Certainly. But that’s nothing new: I’ve spent the last twenty years of my life projecting my life into her words. I hope she realizes how powerful that experience has been.

SE: I think about the kind of grace it must require to allow other people (many, many other people) to fit your words into their own lives in ways that might not always work. Like this slideshow montage set to “Smoke and Ashes,” which you must watch and I am not going to spoil for you with a description:

Or maybe it’s hard to have grace about it. Maybe that’s why we haven’t heard anything new in so long. I don’t know. But there is, for me, this: in that same cinematic way I heard “Fast Car” at fourteen, there are these moments in my life where I feel like I’m about to dive off of the edge of a cliff into a new self, into a new life, and when I listen to Tracy Chapman fucking tell it, those moments feel a little less solitary. I have, as she says, a feeling that I belong — to this tender, fragile world where we aren’t alone in our struggles. And that’s not enough, not really, but it’s also everything, isn’t it?

With five academic degrees between them, Anne Helen Petersen and Simone Eastman can no longer simply “enjoy” anything. They’re ready to talk with you about the Chapman cover of “O Holy Night” for the rest of the month.