My Long-Lost Cousin the Vampire: A Not-So-Philosophical Search for Ezra Koenig

by Lucy McKeon

“Richard McKeon (April 26, 1900 — March 31, 1985) was an American philosopher.”

What I know of my grandfather, born at the unimaginable turn of the 20th century and gone two years before I was born, was primarily from family lore. Almost everything else, I learned from his Wikipedia page.

“He taught Aristotle throughout his career, insisted that his was a Greek Aristotle, not one seen through the eyes of later philosophers writing in Latin. McKeon’s interests later shifted from the doctrines of individuals to the dialectic of systems.”

His ceremonious turkey-carving, during which all Thanksgiving guests would await their drumstick or breast in stiff tension as pieces of meat were sculpted tableside with uneasy exactitude, was material for endless family satire.

“He advised UNESCO when (1946–48) it studied the foundations of human rights and of the idea of democracy.”

He displayed an undisguised lack of interest in his children once they reached a certain age (was it competitiveness?).

“McKeon was a founding member of ‘The Chicago School’ of literary criticism because of his influence on several of its prominent members (e.g., Wayne Booth).”

An unrelenting love for precision made him logical to the extent that he could, in all seriousness, say things like, “It’s not that there aren’t any cabs, Michael, it’s that they’re all taken.” (For this sort of thing he was parodied in The Pooh Perplex by Frederick Crews [1963] and Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance [1974].)

“Former students of McKeon have praised him and proved influential in their own right includ[ing] … authors Susan Sontag and Paul Goodman.”

But until recently, the most important thing Wikipedia had offered me, casually following the mention of his teaching influence and legacy, was this little nugget: “Ezra Koenig of the rock band Vampire Weekend is his grandson.”

I clicked on the lead singer’s name and was brought to Ezra’s Wikipedia page, which confirmed, in similar single-sentence fashion: “Ezra’s maternal grandfather is philosopher Richard McKeon.”

This was news to me. I’m an only child. I’ve always been curious about what it would be like to have siblings — and, I’ve been told, both vehemently requested them and absolutely forbade their existence during competing extremist eras of childhood — but this all seemed a bit sudden, even by long-lost relative standards. What would this mean in terms of holidays? What other secrets lay hidden beneath the public record and dinner-table family lore?

Still, if you’re to discover a long-lost sibling — or even secret half-sibling, close or distant cousin — all the better if he’s famous, I guess. In 2011, when I first made my Wikipedia revelation, I only knew that one Vampire Weekend song “A-Punk” (I missed 2010’s Contra), and though I was amused by the whole thing — and had an enjoyable yet ultimately unproductive internet sleuthing session with my father, who was equally dumfounded and intrigued — I soon forgot all about it as the first semester of graduate school took over my time and mind.

Yet every now and then, my imagination would wander to that untapped potential sibling and our reunited familial bliss. Chanukah with the Koenigs would allow me to finally experience my father’s abandoned culturally Romanian-Jewish ancestry. Thanksgiving in New Jersey, a combination of my Southern mother’s clan in from Georgia and Missouri and Koenig’s Northeastern kin, would include grits, hominy jalapeno, greens, rugeleh and brisket (working with scant material here). If Ezra had any grandparents left, maybe I could inherit them, too, since I didn’t have any more myself (and through irrational logic, if there was any truth to my grandfather’s disloyalty, which didn’t seem out of the question, I felt Richard McKeon sort of owed me this extra set of grandparents — for straying from his wife, for not being the best dad to my father, for dying before I was born). When I heard about his sister Emma’s blog “F*CK! i’m in my twenties,” I pictured collaborative doodling in our future.

But mostly, I didn’t think about it too much.

Then this spring I heard that Vampire Weekend would be releasing their new album Modern Vampires of the City (the title an alluring reference to Junior Reid’s One Blood). I’d recently embraced Twitter after a few years of three-fourths apathetic luddite-ism, one-fourth principled resistance. I started following Ezra and Emma both and was entertained by their tweets, chuckling from afar and feeling a little like a pervy peeping tom who might also be a long-lost half-something. What did they think of the Wikipedia mystery? Did they have answers? But when I checked the two Wikipedia pages for the first time since 2011, our familial bond had been removed.

The erasure only increased my urgency: I would not be deterred. I had to get to the bottom of things. But really though, how could this random life detail even be thought up? There had to be an ounce of truth — or at least something that might lead to something approaching truth — at its core. “Wisdom’s a gift but you trade it for youth. Age is an honor — it’s still not the truth. We saw the stars when they hid from the world. You cursed the son when it stepped to your girl,” Ezra sings in “Step,” a love song for New York on the new album (with most obvious reference to Souls of Mischief). Tell you the truth, it was hearing these lyrics that made me want to finally claim him as the brother I never had.

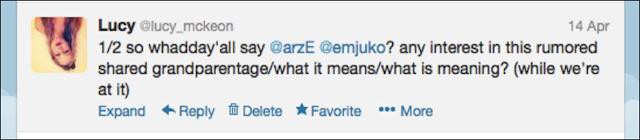

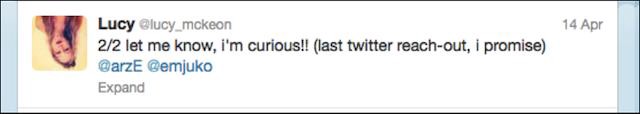

From Wikipedia copy-pasting, the reference remained, mostly on random French-translated bootleg biographies, for whatever reason. It took me 20 minutes to craft the perfect tweet and about a week to send it.

I imagined I’d get a response within the day, because that’s how Twitter works, right? But I waited in vain. After four days and counseling with a friend/Twitter advisor, I decided that I could send another tweet. They must just have missed the first one.

It’s pretty hard to read now (the repeated “y’all,” an attempt to ingratiate myself, reads shamefully false, no matter if I say it in life or not). But, come on, I reasoned, they aren’t the kind of famous where strangers are constantly tweeting their ears off, are they? Trying to showcase my friendliness and potential for humor in 140 characters or less proved difficult. Was the extra exclamation point too much? Did I sound like a crazed fan, or the cat-lady version of a conspiracy theorist? Whatever, it didn’t really matter; this is the internet. I was supposed to be flinging revealing shit at other people’s walls knowing that 90 percent of what stuck would embarrass me later. That was the point. Let the record show, though, that I didn’t feel great about things, even then.

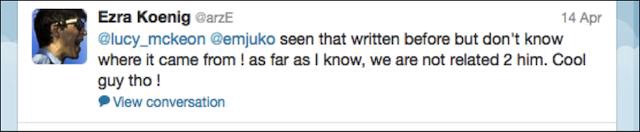

Aw, Lord, not a month of actively tweeting and I’d officially received my first pity tweet. And it was such a nice one, too, that it only made me feel more attached to Ezra as the brother I’d never had, and sad for myself as the child who’d at one point wanted siblings so desperately. I never heard from Emma.

It was also clear that I hadn’t yet mastered the art of self-representation in 140-characters. If I had, surely he would have agreed to investigate — or, if we were to give up on any possibility of the rumor’s truth, he would have wanted to laugh about the randomness of it all over a glass of something and a couple family photos albums just for kicks. I stand by this.

Vampire Weekend is known for its Internet-adept, post-modern approach to music — they’ve consistently brandished allusions across time (’70s rock, for example) and geography (west-African pop) in their albums. It felt fitting that we might at least dip, tongue-in-cheek, into an unexplored and actually nonexistent past together, dispatched by the don deity himself, Wikipedia.

And the fact that the apparitional Wikipedia page for my grandfather the philosopher (the man drawn to a new, expanded rhetoric that might encompass modern change and technology, if his crowd-sourced online bios are to be believed) guided me down a rabbit hole of philosophy blogs and Vampire Weekend music videos, encouraging me, finally, to embrace a widespread tool of social media — that my grandfather urged me to do all this from beyond the grave somehow makes sense. All issues are ultimately philosophical questions, Richard McKeon was known to say. It’s not so much the truth that matters here, but the process by which we interrogate around it.

As it is, it seems that Ezra Koenig and I are not relatives, even of the chosen-across-the-internet variety. But I still hold out hope for family secrets, true or not, yet to be revealed with age.

Lucy McKeon is a New York–based writer and photographer. Her work has appeared in The Nation, Guernica, The Paris Review and elsewhere.