Interview with a One-Time “Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow”

by Leslie Anne Jones

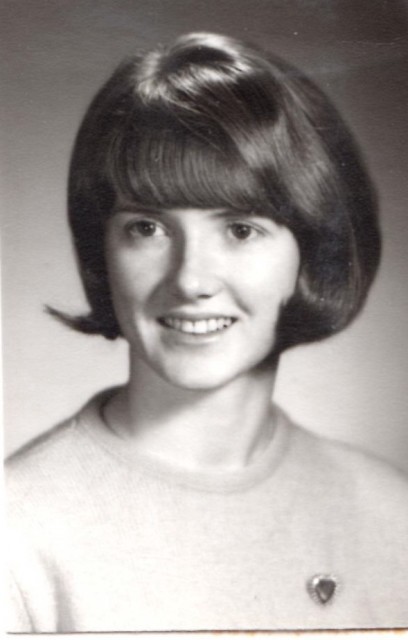

In 1968, Sandra Jones won her high school’s “Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow” Award. She did this by proving her literacy in the realm of “childcare, family relationships, money management, household upkeep and morality,” but she tells me — her daughter — that she was just good at taking tests.

Though domestically savvy, my mom only applied her homemaking skills in her off hours. She was an architect who traveled all over Alaska working on schools and military facilities and made partner before I was born. So, growing up, it never occurred to me that some people still might think women were less equipped to lead than men. Why would it? My mom was the boss, despite having grown up in a time and place (the Oregon Coast) where men were loggers and millworkers and women were nurses and grocery store clerks. When she started high school, the district had just newly introduced competitive sports for girls, and General Mills was still sponsoring these contests for young ladies who could shine in the area of “hearth and home.” Equality was not a given for my mother, but somehow she made it so.

As I bushwhack my way into my own career, I’ve become more and more curious about my mom’s early homemaking triumph and the impressive career that followed. I spoke with her recently about why and how things played out the way they did after she’d received the Betty Crocker award.

How were you selected as Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow?

There was a written test. It took less than an hour, it was multiple choice. Everybody [only girls] took it at the same time, like we were taking the SAT.

What was on the test?

I remember some questions about child rearing — probably other questions about nutrition, meal preparation, family budgeting.

Do you remember any questions specifically?

Yeah.

You’re having a dinner party and you notice your husband has a spot on his tie. What do you do?

A) Point and laugh and make a big noise about it.

B) Quietly let him know.

C) Ignore it because you can’t do anything about it.

It was a tough question. Obviously, point and laugh is not the right answer. But if you can’t do anything about it, is it better to let it be, or should you let him know?

What happened when you won the award?

I got this little silver heart that said “Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow” and there was a write up in the paper.

Were you excited?

I liked the silver pendant.

Did you ever actually want to be a homemaker?

No, never.

What did your mom think about careers and education?

My mom used to say, “Oh, if you went to the University of Oregon you could take secretarial science.” That was a legitimate degree at the time. I know she’d wanted to be a nurse but didn’t have the money to go to nursing school. She wound up working after high school and then going into the Women’s Army Corp, so I think she recognized the importance of education.

How about your dad?

He respected women who worked. Certainly, there were plenty of men in that era who were like, “A woman’s place is in the home.” But how could he have thought like that when my mom was in the service in World War II, in places that were being attacked? He was in the navy but he never got fired on — it was my mom that did.

When did you know you wanted to be an architect?

Probably about sixth grade. I was always looking at the house plans my dad (a plumber) would bring home. From my dad’s work, I knew there were hardly any women in construction, and that being a general contractor as a woman would have been extremely difficult. But I thought as an architect I could still be involved.

In high school I remember we had to do career reports, and at the time I think four percent of architects in the U.S. were women. A pretty small percentage, but it was possible.

How many women were there in the architecture program at the University of Oregon?

There were six other women in my class that I knew of.

You were in college in the late sixties/early seventies. What was your relationship to the feminist movement?

I read Ms. Magazine on a regular basis. It had just come out. Some of the articles really made sense to me and sometimes I would read things and think, “That’s just wrong.”

I think the biggest disagreement I had with anything in the women’s movement was the anti-male aspect of it. You can embrace change without fighting the people you’re going to be working with.

What were the impediments to women who wanted to enter architecture?

If you were trying to get commissions, there was more trust in men. People with the money — the superintendents of the schools — they were mostly men, so they gravitated towards giving power to other men. But I think [my partner] Jon Kumin and I were very good at interviews.

Has that changed over time?

If you’re trying to go after big commissions, I think it’s still pretty male dominated. It’s easy to be a woman that’s on a team that includes men, but I think if you went into a meeting with an all-women team, people will still think you’re not going to cut it. There are obviously some women architects who have been very successful, but those are the superstars.

Did you worry about how having kids would affect your success?

No.

But you didn’t start until you were 37. Your career might have been different if you’d had my little brothers or me earlier.

I wasn’t in a rush to have kids, and I knew my career definitely would have slowed down if I’d stayed home. But I also wouldn’t have wanted to select a career that meant I had to forgo kids and family.

Do you think women who value their careers should delay children?

Not necessarily. The career is still going to be there if you want to work at it. I think there are clearly some advantages to having kids younger, but I’m not sorry about what I did. It worked out fine!

It probably helped that you and Dad were equal partners in the household stuff?

We were. Dad didn’t enjoy accounting so he was more than happy to cut back his hours and pick you guys up from school.

Do you think you would have been happy as a homemaker?

Hypothetically, sure.

Would you have felt like you missed out?

Oh, probably. But there are other questions in that homemaker question — when? where? how much money do we have? how many kids? Careers can be overrated — when you’re working full-time there’s less time to be a volunteer in the community and of course you have less time to spend with your kids. I certainly would not have been happy as a homemaker with no money and a passel of kids who needed braces.

It really just depends. I will say that being a stay-at-home mom, if you have adequate income, does offer a lot of freedom. I think my mom was a good role model for me — she was a homemaker, but she also answered the phone and did the books for my dad’s business. She was on the PTA, school board, the Lady Elks. She had a lot of community involvement, and most importantly, she was happy.

Leslie Anne Jones is a writer and editor. She spent three years working in Shanghai and Beijing and is presently based on the Oregon Coast.