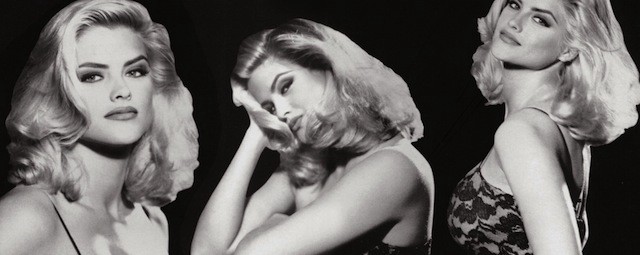

The Anna Nicole Smith Stories

by Durga Chew-Bose and Sarah Nicole Prickett

Never mind the madman in Armani; Mary Harron’s on side with the whores. Our beloved American Psycho director is back with The Anna Nicole Smith Story for Lifetime, which is kind of a punk move, if you think about it.

Harron’s biopic, which premieres Saturday, June 29, skews closely to Lifetime conventions while upholding her commitment to the fringe. After all, Harron also directed I Shot Andy Warhol and The Notorious Bettie Page. With Anna Nicole, we get the girlhood traumas, a mother’s sins, and the absent dads. We get the makeover montage of TV-melodrama dreams. And we never forget that under the bottle blonde and bowling-ball tits, Smith’s a good old American MILF.

In Agnes Bruckner’s portrayal, she starts out looking like circa-’99 Britney, if Britney went to Dillon High, and ends up the perfect (dead) embodiment of her idol, Marilyn Monroe. No spoilers or whatever, but trust: You haven’t seen “the glamorization of female suicide” until you’ve seen how The Anna Nicole Story ends.

The unspectacular addiction, and Smith’s childlike affection for those she loved, make this a sympathetic, almost un-tabloid-ish picture. Harron is a director as tender as she is morbid. Which made us think: Would The Anna Nicole Smith Story by any other independent filmmaker be as sweet?

Let’s review.

Pedro Almodovar

“Baby,” says a Playboy photographer, watching Vickie Lynn Hogan become Anna Nicole Smith before his lens, “some things are unmistakably American.” Other things are unmistakably Almodovar. In It’s Expensive to Be Me, the Spanish director’s take on a super-sized life, womanhood meets all possible influences: Champagne rains like men; pills pop and get popped; syringes fill with hot pink blood. Every photo shoot is a striptease, and every striptease is a musical number, culminating in a Marilyn Monroe-to-Rihanna medley with more real diamonds and fewer bras than a Cannes premiere. Audiences everywhere are composed entirely of Gael Garcia Bernals. Vickie-cum-Anna is played with equal parts gin and chagrin by a startlingly bewigged Salma Hayek, who marries not for money, but to hide her past — as a boy. Hayek’s “Tranny Nicole” borders on buffoonish; her mother (a baffled-seeming Brigitte Bardot) has the opposite problem, one of stiff-bosomed boredom.

Still, it’s hard to resist Almodovar’s joyful gimmickry, especially when it comes (and comes, and comes) to the hyper-sapphic affair with housekeeper Maria Antonia Cerrato (Penelope Cruz) that ended in the latter suing Smith for assault. By the time Smith’s writhing in nothing but clown makeup and a crucifix on the chorus-lined grave of her son Daniel (Elle Fanning), our laughter and weeping are as indistinguishable as they should be. 4 out of 4 stars.

Kathryn Bigelow

In 42DD, Bigelow spares not a cringe. The six-minute opening sequence, filmed with a precision to match what’s depicted, close-ups each slice and squirt required to give Anna Nicole Smith (Amy Adams) the tits that made her name. Sit through this and feel rewarded with a relentlessly calm, well-paced march through Smith’s very adult life, as though a hotel escalator is descending into hell. Adams’ Smith is a dazzling, shifty gold-digger, her plots illuminated by gestures, not word, as small as her physicality is overwhelming. Her son appears rarely. She is neither cruel nor sympathetic, a Xanaxed surface on which light becomes diamond and motives lie in shadow. Her mother is a raspy voice on the phone. Adams’ face, which looks almost nothing like Smith’s face, is most alive behind the wheel of her scarlet convertible, and deadest when she’s seen fucking, with cold anatomical accuracy revealed in knife-like camerawork, a series of able-bodied men. Her Paw Paw (Clint Eastwood) appears first when she’s leaving him, on their wedding night, to fly overseas for a photo shoot.

There are no flashbacks to childhood, or of any kind. She never cries or asks a question. When an implant ruptures, bursting Smith’s nipple, Bigelow flaunts her genius for destruction without heat. A geyser of saline proves indelible. Midway, the film elides addiction, rehab, and redemption to become pure courtroom drama (mostly: the mega-publicized battle for J. Howard’s billions) with Smith’s live-in lawyer, Howard Stern (Parks and Recreation’s Adam Scott), stealing scene after scene as she slips beyond sympathy into a total void of emotion. Daniel’s death by toxicity is seen through Stern’s camera, and the final shot is a one-to-one representation of the iconic tabloid image: Smith makeupless in her hospital bed with the greening corpse of a boy in her arms and, out of frame, a new baby girl. A single tear rests on her cheek. 3 out of 4 stars.

Sofia Coppola

The opening shot of Sofia Coppola’s sixth feature, Anna, is a slow pan of a woman’s bare legs standing beside a stainless steel pole. We begin at her thighs and soon land on her eight-inch Lucite heels. We stay there until a dollar bill floats down. It lands on the stage just as Phoenix’s cover of Chris DeBurgh’s “Lady in Red” begins: I’ve never seen you look so lovely as you did tonight, I’ve never seen you shine so bright. The song plays in its entirety as a few more dollar bills fall in between flashes of whirlybird LED lights and glittering dust particles. What happens next is the story of Anna Nicole Smith, played by Friday Night Lights’ Aimee Teegarden and, later, Kate Upton.

The film unfolds in the most leisurely manner; it’s as if it’s been coerced from the screen. In one scene, we watch Smith fill four complete pages of her diary in bubbly cursive letters. Nearby, her toy poodle, Sugar Pie, wrestles with a fur pillow while her lawyer-manager-best friend, Howard K. Stern (Jason Schwartzman), negotiates a deal with E! on a crystal-bedazzled phone. Later, Smith shoots her famous 2004 “TrimSpa, Baby!” commercial as Ellie Goulding’s 2011 hit, “Lights,” soars. Coppola’s offish mismatching of song to scene fashions Anna into a breezy benzo dreamscape, like sitting shotgun in a car, never having to focus on the road: a fleeting view, a song, zero urgency or obligation. Sofia’s spell rarely works on those who can drive. As with Coppola’s previous films, children parent parents, fame contaminates, and loneliness prevails.

Clasping a bag of pink pills that match her pink Harry Winston jewelry that match her SPOILED pink t-shirt she later wears in court, Smith stares out her window longingly. With less than five pages of dialogue, Upton is seen, for the most part, resting her head on a pillow, eating room service, tanning, looking very Picnic at Hanging Rock Cafe, touching knickknacks, laying in a gilded bed while lo-fi Julian Casablancas strums away, shielding herself from paparazzi, running her fingers over PVC halter dresses, tanning some more, swimming in Hockney-blue pools with her son, biting her lip, talking to an ex on the phone, professing teenage-type love, twisting open pill bottles, hiding her tears behind sunglasses, bonding with strangers at bars, and throwing her arms in the air just like Marilyn. It’s Smith’s big tragic life made to fit Sofia’s gossamer world. 1 out of 4 stars.

Todd Haynes

The master of quiet American melodrama gives us Anna Nicole not with a heart of gold, but with a queasy, shimmering soul. A de-gaminified Mia Wasikowska plays Vickie Lynn Hogan, the titless stripper and 20-year-old single mom from Harris County, Tex. Kristie Alley embodies Smith as her reality-television self, the slurred lines mercifully few. But for most of the film, shot in a series of empty, overstuffed rooms in which Anna Nicole is almost always alone but never naked, America’s consummate myth is played — with cool fire and a fuckload of bleach — by Kate Winslet. What other actress could make a slip-on pair of 42DD tits feel natural? Still in her decade-long prime, Winslet makes a well-oiled portrait of the tabloid star at home. She applies and removes false lashes. She counts pills. In one scene, lit by 4 a.m. infomercials, she pulls out 64 individual strands of hair. And she longs, she longs — just not for men.

Brief and desultory are the scenes in which she gets money, implants, and the slavish attention of octogenarian billionaire J. Howard (Leonardo di Caprio). Devastatingly protracted are the stares exchanged between Smith and a glamorous but unfocussed milieu of other women: Strippers, then housemaids, and finally, the prying young nurses at a Bahamian hospital. Haynes instills in Smith a growing horror that her son, Daniel (played as a teenager by Dane deHaan), will be gay, coupled with an increasingly disturbing, totally serene non-acceptance of her own sexuality. When Daniel dies, Smith speaks for the first time in the film’s last 20 minutes, declaring herself his only lover. She threatens to bury herself with him.

The film, in which the early 2000s look uncannily like the late ’60s, ends on a shot of tightly closed rosebuds. We see neither the birth of Daniellyn nor Smith’s suicide, and we don’t need to — Winslet gives us a walking, breathing corpse more horrifying than any freeze-flash of blue flesh. 3 ½ out of 4 stars.

Harmony Korine

In Candyland, Twins Sidney and Thurman Sewell — also known as the ATL Twins — are living in a unfinished, abandoned Houston mansion that doubles as “DoubleD,” a clubhouse honoring the late Anna Nicole Smith. Think Dollywood for misfits: it’s bedecked with stripper poles, bronze pony statues, and Bobby Trendy velour sofas. Life-size Anna Nicole cutouts line the walls and her 1992 lipstick-red Mercedez Roadstar hangs like a Hot Wheels chandelier from the mansion’s cathedral ceiling. Depicting various years of her life, Anna Nicole impersonators (played by Chloe Sevigny, Miley Cyrus, David Blaine, Rachel Korine, Die Antwoord’s Yo-Laandi) people DoubleD’s hermetic world in the most deliriously triumphant manner, as if it were nothing more than a figment of their imaginations — provisional at best.

In one scene, Sevigny ambles up and down the stairs humming a spooky tune and wearing clown make-up. We follow her as she pets a feather boa and crowns herself with a Vegas showgirl headpiece. She starts humming louder and louder, and soon, the tune is unburdened and becomes something familiar and sweet: Lesley Gore’s “Sunshine, Lollipops, and Rainbows.” Sevigny’s face warms and beneath those thick layers of paint, her eyes widen as if she knows something we have yet to find out. Everything that’s wonderful is sure to come your way, ’cause you’re in love, you’re in love, and love is here to stay… 3 ½ out of the 4 stars.

Steve McQueen

Religion stars Jennifer Lawrence as an uneducated single mother from Harris County, Tex., devoted to God and son. Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” plays at Gigi’s as the 20-year-old Anna Nicole Smith lists against a stripper’s pole, her lush curves coming off cold. At mass with her baby Daniel, she struggles to hide new, huge breasts, even while her rapist father and probable-rapist priests eye her over the aisles. The breasts grow; the rest of her shrinks, under the burden of them. As she ascends to Playmate fame, her blue eyes turn glassier and glassier, glittering in the spotlight like blood diamonds. She’s wracked with back pain. Her son grows older, turns away.

Lawrence deals admirably with a script that feels like B-side Arthur Miller, but McQueen seems more interested in her thighs than her lines. Smith’s weight losses, then gains, are depicted with golden-hued relish. Her snowballing sexual trysts have the quality of feminist porn. Guilt is measured in pills, which are counted like beads on a rosary, and in ritualistic purgings after pizza. She wears her wedding dress to J. Howard’s funeral. When Catholicism seems not to suffice, she turns — in rehab — to an amorphous form of Judaism. One of the film’s most-staged scenes occurs after Daniel’s death, when Lawrence mutely covers each window in the same heavy, black cloth as the curtains at Gigi’s. Perhaps she knows how your eyelids feel. There is not one moment in this film that feels free of a punitive fate. ½ out of 4 stars.

Gus Van Sant

Nearly two decades since her darkly comedic, award-winning performance as Suzanne Stone in To Die For, Nicole Kidman reunites with director Gus Van Sant in Prefer Blonde, a fictional portrait of the life of Anna Nicole Smith. In part allusive yet plainly borrowing from the model-actress cum TV personality’s story, Van Sant shakes the diagnostic trappings of biopics in favor of something less patent. For one, Kidman plays a woman named Hope whose likeness to Smith has less to do with double-D boobs and bottle blonde hair, but instead a deep sadness turned dullness that keeps Hope indoors, tethered to her bed and bathroom in her million-dollar Bahamas mansion. The mundane has become a brilliant series of gradual, near-devastating tasks. With her lawyer and only friend (James Franco) by her side, she feeds her newborn formula in the same carelessly doting fashion a child plays pretend with a plastic doll.

In one scene, we watch as Hope crawls into bed with a life-size photo of her recently dead son and begins to sing, as if it were a lullaby, “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend” — a far cry from Kidman’s Moulin Rouge rendition. Meanwhile, found footage from a lost interview on Entertainment Tonight — in which Hope, temporarily sober and promising never to relapse — is intercut throughout the film. Looking healthy with her skin the texture of fondant, she repeatedly refers to herself as “little old me,” giggling in between answers; she’s “tickled to death with happiness,” she says.

Kidman’s depiction of Hope as Anna Nicole is twofold — a women whose life portrayed in pixels could never overcome or outperform her past try as she might. It’s gorgeously shot, slow-paced and washed-out; the movie resembles sundried celluloid. Faint and unintelligible in some scenes, Kidman’s voice is the memory of a voice — a ricochet. Near the end, while applying lipstick in the dark, she asks her lawyer to turn on the TV. “Would ya… would ya get the tel-uh-vision.” She misses her lips entirely, unwittingly painting a bright pink grin on her face. 3 out of 4 stars.

Durga and Sarah are recently reunited blood sisters from Canada.