The Oldest Girls

by Megan Gilbert

This is the first installment in a series about summer camp.

Vicki, Cathy, and Michelle ran Oldest Girls with an iron fist wearing a lacy fingerless glove. In 1985, these three teenage girls were the most powerful regime I had ever encountered; fueled by hormones and boredom, they ripped me from the world of Cabbage Patch Kids and roller skates to the world of drinking warm schnapps out of a plastic margarine container in the woods. I’m not sure why they chose me, I’m just sure that they did.

•••My parents sent my sister Kim and me to day camp every summer. Not a fancy overnight camp — day camp. At Camp Massasoit, four two-week sessions were held over the course of a summer (meaning, you had to pack a lot into two weeks). The camp was affiliated with Springfield College, where my dad worked as the Assistant Athletic Director, and was situated on what was known as the college’s “East Campus,” nestled between the Monsanto chemical plant where half of my old relatives worked half of their lives, and an on-ramp to the Mass Pike. Despite its less-than-rural location, we campers enjoyed several varieties of northeastern trees, the requisite (albeit contaminated) lake, two ball fields, and even a pueblo (in which we sat on rainy days, making God’s Eyes out of yarn and popsicle sticks and chucking empty chocolate milk cartons at each other). My mom drove us to camp in the morning, and Dad would pick us up after work.

Even as a young girl I knew where my camp landed in the pecking order of New England’s many camps. I imagined that the overnight camps, situated deep in the Vermont woods or on sprawling farms in northern Connecticut, offered their campers miniature log cabins with gingham curtains sewn by woodland creatures, breakdancing instructors, acting lessons from Michael J. Fox, and a selection of gentle, fawn-colored horses. Camp Massasoit was (and still is) a repository for sons and daughters of Springfield College employees and Pioneer Valley’s population of borderline juvenile delinquents. Most of us had parents like mine that worked blue-collar or low-paying professional jobs in places like Chicopee or Agawam, Massachusetts. Neither of my best friends from Springfield, my hometown, went to my camp; Jen was busy jumping on a giant trampoline and taking jazz dance at Sunnybrook Acres and Julieanne was babysitting.

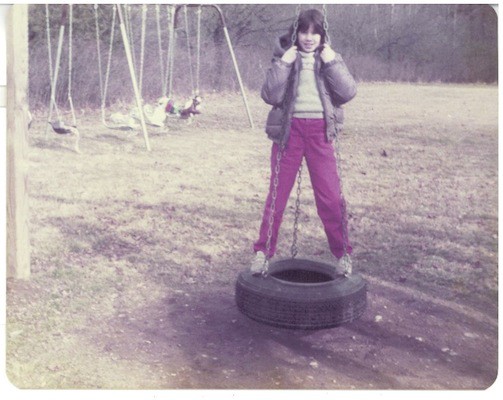

The summer I turned 11 was my fifth year at camp. I had been singing the canoe song and falling in love with counselors 10 years my senior for what seemed like ever. Camp was divided into two-week sessions, and campers were divided into age groups made up of about 10 kids, the most envied and feared of which were known as “Oldest Boys” and “Oldest Girls.” No one knew what group they were in until the first day of camp, so when my name was called for Oldest Girls (technically, I was on the border between Oldest and Second Oldest), I turned bright red, extracted myself from the non-threatening pack of 10-year olds I had scared up, and walked my baggy shorts and basketball camp T-shirt across Council Ring toward a mob of long-haired 13-year old girls wearing fluorescent short shorts and spatter-paint sunglasses on day-glo lanyards. Holy shit.

The first day or two, I did my best to never speak. I hoped the Oldest Girls’ triumvirate of power, otherwise known as Vicki, Cathy, and Michelle, would skim their eyes over my head, never to rest on my pale and petrified face. (I figured this would happen naturally, as they were all about a foot taller than I was.) Vicki, the leader of the pack, sported a Woonsocket, Rhode Island teased blond mullet, a scowl, and a penchant for doing whatever the fuck she liked. Cathy, Vicki’s sidekick, looked not unlike the cartoon character: she had huge glasses, brown curly hair, and a mouth full of metal. She seemed destined to be unlucky in love, all the while dotting her i’s with plump, hopeful hearts. Rounding out the group was Michelle, an exquisite, six-foot-tall black girl, who I guessed was recruited mostly for her beauty but perhaps also to balance out the power structure with a bit of sweetness. And then there was me — inoffensively shy, recently permed, sometimes bespectacled, makeup-less, in between. I hung in the middle of the group like a mildly interesting partygoer, invited by a friend of a friend, never letting my full personality — or however much of it had formed — show. My friends in Second Oldest Girls had seen it, my parents had seen it, Jen and Julieanne had seen it, but in the presence of Vicki, Cathy, and Michelle, I couldn’t bring myself to exist.

•••On day three as an Oldest Girl, as I stretched out on a picnic bench, mentally preparing to walk down the ferny and gravel-strewn path to the archery pit, a shadow passed over me.

“You need to shave your legs.”

My heart froze. I might have peed a little. Standing above me, were the Big Three — Vicki in front, arms crossed. I squinted up at them, partially blinded by the July sun that seemed trained on their every movement.

“Yeah…” I managed. Until that moment, I had honestly never considered the subject of shaving, unless you count watching my dad lather up an ancient horsehair brush and cover his face with white foam.

“Yeah. And why are you wearing those baby clothes?” This came from Cathy, her head sprouting from Vicki’s left shoulder.

“Uh…I dunno…” As I searched for an explanation to another phenomenon I had never contemplated, the deafening foghorn sounded, signaling a change of activity. I bolted up, stood eye-level with Vicki’s training bra for a split-second, and sidled around their formation and into the throng of campers headed to boating or riflery. I had never before been so thrilled at the prospect of strapping a quiver full of arrows to my back.

As I half-jogged away from the girls, a kind of heat I would come to know as a combination of exhilaration, humiliation, and hormones emanated from my armpits and shins. Was I about to spend the next two weeks an object of ridicule? Or, wait a second: had I been recruited? That was possible, wasn’t it? Why would the girls pay attention specifically to me when there were a bunch of other braless freaks like me wandering around camp? I must have potential. Potential to be Number Four.

Five o’clock saw me obsessively sipping a can of Welch’s Grape Soda in the parking lot, shifting my weight from one foot to the other, staring into every white Pontiac that crawled through the camper receiving line, looking for the dim outline of my father. I was ready to get home and get started.

I had to make some serious changes.

•••At home, I ran a bath. I stole my mother’s disposable razor from the medicine cabinet, and placed it on the corner of the beige fiberglass tub. The water ran burning hot, then tepid. I dampened a pink washcloth that matched the eyelet curtains, ran it over my camp-grimed face. Washed behind my ears. Then it was time.

My legs seemed foreign, like a boy’s legs, or an animal’s. I examined each downy hair on my shins, and began soaping them with Camay until the bar crumbled in my hands. Terrified, I held the razor over my right leg, eyes tearing, hands soapy and shaking, and practiced the motions I imagined I was supposed to do in order to free my Neanderthalish limbs. I couldn’t bear to bring the blade to my skin. The steam from the bath had dampened my brow and the nape of my neck. The steam, and the terror.

“What are you doing in there? Dinner’s ready!” My mother’s voice thundered through the bathroom door.

“Nothing! I’m almost done!” I screamed, dropping the razor into the filmy water. I knew she was coming in. My mother was always coming in.

“What are you doing?” My mother now stood in the bathroom, right hand on the doorknob, left hip slung forward. A dishcloth clung to her left shoulder. Steam rushed by her into the hallway, fogging her glasses on the way. She was pissed.

I grabbed the washcloth and clutched it to my new breasts. “M-O-M!” I screamed in three syllables, both outraged and relieved. I burst into tears. “I’m shaving my legs these girls at camp told me I had to and my legs are so ugly I can’t go to camp tomorrow with hairy legs all the other girls at camp are shaving” I blathered.

My mother came over to me, fished the razor out of the tub, helped me up, wrapped me in a cream-colored towel and began wiping away bathwater and tears. After dinner, she patiently showed me how to measure the shaving cream in palm of my hand, angle the blade against my shinbone, pinky extended, and then merely wince and glide. I rummaged though my dresser drawers, looking for the most grown-up campwear I could find for the following day — more specifically, looking for the shortest shorts I owned.

The next morning I set out for camp in a pink and purple ensemble, pink shorts with a stripey shirt. Collar up. No socks with my Keds, hair sprayed up into a kind of soufflé. Sunglasses. Lanyard. I was so Number Four.

By the end of the day, I was firmly in place. By the end of the two-week session, I could be seen prancing around camp, ignoring everyone but Vicki, Cathy, and Michelle, including my own sister. I was also the proud owner of my first boyfriend, Jamie — he of the Van Halen painter’s cap with a mudflap at the back. When he took it off, his hair was the exact same shape. We were devastatingly cute together, which was why Vicki picked him out for me.

Earlier that week, après-shave, Vicki had asked me who I “liked.” I had stammered, “Um… this guy at school.”

“What’s his name?” shot Vicki. She was twirling the ends of her stringy blond hair into points, then chewing on them.

“Jason.” It was the first name I had thought of. All of the Jasons I knew were cute (especially Jason Bateman). “He’s a breakdancer.” I threw that in there for effect.

She looked intrigued. “Is he your boyfriend?”

“Well, not exactly. I mean, we like each other, we’re friends and everything, but — “

She was not amused. “You need a boyfriend.” She scanned the crowd of campers gathered at Council Ring for announcements. “What about that one?” She pointed toward the Oldest Boys, a hair twist whipping out of her mouth, dark with spit. I knew she was pointing at Jamie. He was the skinniest, youngest-looking kid in the group, so we matched. And he was staring at us. I looked away.

“I guess he’s cute.”

“Who’s cute?” Cathy and Michelle had appeared, freshly lip-glossed.

“Megan likes Jamie!” Vicki declared. There were squeals. It was a done deal now — there was no way I could convince all three of them that this Jamie thing was a huge mistake. But I couldn’t tell whether the pit in my stomach was revulsion or excitement. I hoped I would figure it out before sleepover night, the night of The Dance.

•••On sleepover night, the thrilling night before the last day of camp that had nothing to do with sleep and everything to do with sneaking away from one’s campsite in search of marauding boys, I dragged my new pink backpack stuffed with clean underwear, a change of clothes, a towel, and a toothbrush through Picnic Grove to the East Ballfield, where the Oldest Girls’ tent was to be set up — far from the Oldest Boys’ tent, which was down by the lake. Vicki, Cathy, Michelle, and I had sniffed it out earlier that day, just to see.

After the camp-wide bonfire, after tent set-up with the rest of Oldest Girls, and after arranging our four sleeping bags in a snug, best-friend row, Vicki looked at Cathy, Michelle, and I, and nodded. We told our scattered counselor that we had to change, grabbed our backpacks and a long metal flashlight, and set out for the girl’s bathroom. The Dance — for just the Oldest Girls and Boys — was in the Picnic Grove at 9 p.m. And we had plans.

When we got to the girl’s room, a shack with a cement floor and an open ceiling, we waited for a couple of eight-year-olds in jammies to finish brushing their teeth, then stuck Cathy outside as a lookout. Michelle casually rebraided her hair in the dirty mirror. I stood in the center of the dank, piss-smelling lean-to, heart speeding, not quite knowing what we were doing there, although I had my suspicions. Vicki extracted a small plastic container from inside of her bag. It had little yellow ears of corn dancing across it. Holy shit. She had really brought alcohol.

“Hurry up!” Vicki scream whispered, and thrust the container into my hands.

I shook. “What is it?”

“Just drink it! Hurry up!” Vicki glanced toward the door. Michelle had turned around and moved closer to us. “Hurry up! Vicki’s eyes flickered.

I did what she said, to get it over with. The liquid smelled like something my father kept in the garage and took out when he re-caulked the tub. I had never seen alcohol up close before. It was warm and yellow and thick. I tilted it toward my mouth and it touched my lips for a millisecond.

Vicki grabbed the container from my face and drank deeply, then passed it to Michelle, who sipped it a few times, like a grown-up. The door swung open and Cathy’s head materialized, all glasses and braces.

“Is it my turn yet?” she asked. Vicki motioned for her to come in, and I was shooed away to take over door duty.

Outside, it was dark. A few flashlights carved frantic white tubes through the trees. Kids were laughing, which seemed strange. I thought, that’s how laughing must seem when you’re drunk.

That night, after my first sip of alcohol, I endured my first kiss. Even though Jamie and I had been a couple for nearly a week now, we had barely seen or spoken to each other at all. I think he had tried to find me, but if I caught a glimpse of his mullet, I ran to the pueblo or the Chapel of the Pines to hide, flushed with embarrassment. There was no hiding tonight, though. We were at The Dance, and if you were a camp couple, you were supposed to dance.

Vicki, Cathy, Michelle, and I arrived at Picnic Grove giggling and 15 minutes late. Twinkly white lights had been strung on the pine trees and a makeshift snack table/DJ booth had been set up near the parking lot. The guy who stacked the milk crates was playing cassettes on a boom box. I felt warm and pretty. To the opening strains of Berlin’s “Take My Breath Away,” Jamie left his pack of boys, wove through the sea of picnic tables and chattering clusters of girls, and uttered two of the approximately 13 words that ever passed between us: “Wanna dance?”

He had never touched me before, but his pale arms knew to encircle my waist as a peacock’s tail knows to unfurl at the sight of a hen. His lips were unnaturally pink. At the end of the song, they brushed mine for a millisecond longer than the alcohol had, and I figured out a millisecond too late what that pit in my stomach had been: revulsion.

The next day, our last day of camp, I dumped Jamie via Vicki. She decided I didn’t like him anymore, and told him so. And she was right.

That day, everyone cried. The girls wrote their parents’ telephone numbers with strange area codes into my notebook. They drew hearts with little arrows through them. Love, Michelle. Love, Cathy. Stay Cool, Vicki. I never saw or talked to Vicki, Cathy, or Michelle again. Come to think of it, I don’t remember talking to them much at all.

Megan Gilbert’s work has appeared in The Rumpus, Union Station, New York Press (R.I.P.), Paste, and elsewhere. Her legs are smooth and silky. Follow her @ithardlymatt3rs.