Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Ecstasy of Hedy Lamarr

by Anne Helen Petersen

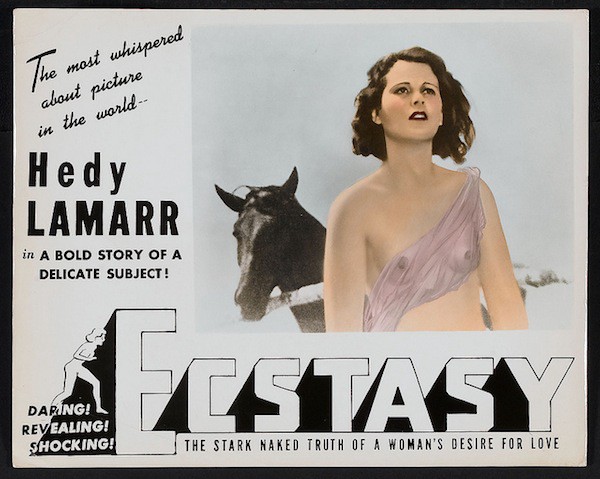

The first time audiences saw Hedy Lamarr, she was running naked through a field. The second time they saw her, she was in the throes of a very animated orgasm. The next time she appeared on screen — more than five years later — she’d have a new name, a new language, and a new image, but the effect was the same: just the sight of her was enough to stop Hollywood, and audiences across America, in their tracks.

But a new name wasn’t enough to distance Hedy Lamarr from her past as the “Ecstasy Girl,” the star of the so-called “art film” that scandalized all of Europe, and received special denunciation by the Pope. When one exhibitor tried to import it to the states, it was declared “dangerously indecent” and uniformly banned. The real scandal wasn’t the nudity, but the pleasure: a young girl abandons her husband, runs naked, finds a new hot guy, and then has a really intense orgasm for all to see. Who knew what young women the world over would do with that knowledge?

With the help of her new studio, Lamarr was able to denounce her part in Ecstasy, but the stigma of the desiring female would stay with her. Over her Hollywood career, she would be cast as one “high class whore” after another — women whose beauty, and sexuality, make them natural victims of the world around them.

Granted, Lamarr was no great actor. Her biggest asset was exotic glamour, her pooling eyes, and her mouth that, according to one description, looked like a poppy in heavy bloom. But she might have been a genius — or, at the very least, a very savvy businesswoman, a bit of a Mathlete, and a closet nerd who is, at least in part, responsible for cellular technology as we know it today. Let me say that again: Hedy Lamarr, arguably the most glamorous star of the pre-war period, also helped invent your cell phone and WiFi connection.

The contradiction between Hedy Lamarr, Sex Object and Hedy Lamarr, Lady Inventor was too difficult for the press to reconcile. It wasn’t until after her death — and decades of missteps and humiliations of various forms and gravity — that her image began to shift from scandalous, washed-up star to celebrated scientist. Today, she’s held up as a sort of feminist icon, with her image employed as a means to encourage young girls to go into science, and all manner of awards and celebrations and symposia held in her name.

But the irreconcilability of sex and brains in one body, and Lamarr’s resultant reliance on her looks (and what they did to the men around her) led to an unhappy, ultimately cloistered life. Today, it’s clear that Lamarr was a seriously complicated and awesome woman; for decades, she was just a broken, bitter lady, the spoiled wreckage of the star system. Lamarr, like every woman, contained multitudes, but the movies tried to make her mean one, very simple one. Like so many female stars, the story of her resistance to that notion was the story of her decline.

Before Hollywood, Lamarr led a life sensational enough to merit its own movie — we’re talking flee-from-the-castle Game of Thrones type shit. Hedwig Kiesler, or “Hedy,” as she was known, was the only child to well-to-do Jewish Viennese parents. Her father was a respected businessman, and young Hedy was given the childhood that befit her class — private tutors, schooling in Switzerland and, when she came of age, a much-anticipated debut into society.

Even as a young child, Lamarr was beautiful. With her pitch black hair, porcelain white skin, and light, gray-green eyes, her mother called her “Snow White.” She was a stubborn, willful child; as she later told a fan magazine, “I used to run my head against stone walls, right through stone walls — and get hurt. But it was good for me. I learned. It is better to get such bumps young.”

But the bumps didn’t stop: before her debut, Lamarr’s father took ill; when he died, he left the family in the depths of the Austrian financial crisis, with only a sliver of their fortune remaining. Hedy reinvested some money in stocks, but everything went to shit. But she wasn’t too proud to go to work, first as a secretary (“she was much too pretty to work in an office”) and then, through a family friend, as a script girl for an Austrian studio.

It was at this studio — sitting around, reading scripts, being beautiful — that she caught the eye of Czech filmmaker Gustav Machatý, who was busy plotting his “great experimental masterpiece.” He thus arranged for the untested Lamarr to appear in a slew of bit parts in order to gain a bit of experience in front of the camera before casting her in Extase (English translation: Ecstasy).

The plot of the film was straightforward: a beautiful but poor girl marries an ugly but rich husband. Yet the husband also happens to be impotent, and the girl escapes to her father’s home, where she runs naked through a field and skinny dips, bumping into a hot young engineer who can give her what her husband can’t. (Namely: hot, hot sex. Clip below is NSFW.)

All the art cinema stuff (dropping of pearls, fluttering of fingers) obscures the narrative a bit (what, exactly, is he doing to her?) but I usually hold old sexy-time footage to a sort of relative scale, given what they could and could not show, but this! This is the real deal. And oh, look! Someone has already made you a sweet masturbatory collage!

You can imagine the scandal, even for a European art film. Here was a desiring woman — a woman actually getting off and reveling in it — and doing so while cheating on her husband. Which is why, when censors took to the film, the first thing they demanded was some sort of clumsy insertion of a marriage before said ecstasy took place. The version that America received had a weird voiceover, kind of like the sort of thing that you get when you try to illegally download something, that just repeated something convincing like, “I’M SO HAPPY WE’RE MARRIED! WOO HOO, WE’RE MARRIED! — YES, MARRIED!” to a confused audience.

Censored or uncensored, this orgasming girl was a sensation. As would later become clear, she had no idea that the film would turn out as “naughty” as it did — but she also had no compunction about parlaying her newfound notoriety into new gigs. She appeared in famed director Max Reinhardt’s new play, The Weaker Sex, and toured Europe to even greater renown.

To much of Europe, Lamarr became known as “The Ecstasy Girl” — and she had also attracted the devout attention of an older, very wealthy, very connected man. When Fritz Mandl first saw Lamarr onscreen, he was in his early thirties and already one of the top four munitions dealers in all of Europe. And once he saw Lamarr, he had to have her. He attended the opening night of The Weaker Sex, asked a mutual friend for an introduction, and negotiated (for lack of a better word) a wedding.

According to Lamarr’s account of the marriage, broadly reproduced after her arrival in Hollywood, Mandl treated Lamarr like any of his other fine, expensive possessions. He would hold court in Vienna, hosting lavish parties that included a who’s who of European society. Lamarr’s task: look pretty, wear jewels, and talk very little. “He always treated me like a doll,” Lamarr reported. “I had to spend all my time giving and going to parties, wearing smart clothes, taking pleasure trips to Switzerland, North Africa, the Riviera…”

The deal sounds OK to a writer still saddled with grad school miserliness, but I guess the presence of all of the Fascist leaders of Europe at the dinner table might spoil things a bit. Can you imagine? Mussolini one night, Hitler another. There must have been lots of idle chatter about world domination.

Lamarr wanted out, but Mandl exercised firm control over her every doing. He was so jealous that he bought and destroyed every print of Ecstasy he could find, searching as far as New Zealand and Japan for any evidence of his wife’s orgasming body. But prints kept popping up — in part because the savvy studio kept making them, knowing Mandl would pay — forcing Mandl to cut a deal: he put down a huge sum for the original print, and the studio promised to never produce another copy.

Clearly, Mandl couldn’t track down every print, but his search underlines the type of control he was able to leverage. When he went out of town, he sent Lamarr to the country home so she could not escape; when she asked for a creative outlet (books, painting, acting), he gave her furs and told her to hush. She could not so much as smile at a guest without inciting his anger; he insisted that she never laugh, lest she look undignified.

Lamarr was trapped, quite literally, in a castle. She tried to escape twice, but was foiled both times. She begged Max Reinhardt for help, but he couldn’t risk it. But Lamarr was clever: she began charging up all of their credit in the Viennese shops, so flagrantly that Mandl had to cut off the accounts and give her cash, which she began to stow away.

At this point, Lamarr either a.) fled with her maid to Paris in the dead of night or b.) drugged her maid, took her costume, and fled to Paris in the dead of night or c.) hid in a whore house, where she was nearly discovered, but instead had sex with a john and stayed safe. It’s hard to know what really happened — some of the details are culled from her memoir, whose publishers she sued for libel (don’t worry, WE’LL GET THERE) — and she might have just walked out the front door and onto the train.

Details! However she did it, she made her way to London, where she met with American agent Bob Ritchie, who in turn arranged a meeting with MGM head Louis B. Mayer, who was in London for business. Lamarr had just happened to stow a fine selection of her finery for her escape, and she just happened to know that Mayer had a thing for glamour. Mayer also had a notorious distaste for scandal of any type — so for him to forget all about the existence of Ecstasy, Lamarr must’ve looked good.

Mayer offered her a short-term contract on the spot, but Lamarr balked at the paltry sum. Still, she somehow found herself on the same steamer to the States and — realizing how dire her situation had become — agreed to Mayer’s terms. She also agreed adopt a new last name to distance her from her previous acting career. At sea, she signed her contract as Hedy La Mer, but it would soon be changed to Hedy Lamarr. (Another take has her named for starlet Barbara La Marr, known as “the woman who was too beautiful.” La Marr had died of a drug overdose in 1926).

Once in Hollywood, MGM gave her the treatment it gave all its would-be stars: elocution lessons (her English was poor-to-bad) and a slew of wardrobe, hair, and make-up tests. They put her in blonde wigs, fancy headdresses, and Shirley Temple curls, all horrible. Lamarr: “You know how it is when you wear an unbecoming hat? And you try to hide your head? That’s how it was with me.”

Or, in words we can understand, it was like forgetting to bring the necessary undergarments to the gym, and then you have to go to work in your sweaty sportsbra and no underwear under your nice work dress, and you spend most of the day avoiding everyone lest your damning, mildly stinky secret be known. Like that.

So MGM let Lamarr stay how she was — pitch-black hair, center part, soft waves, and eyelashes that went on forever. But they couldn’t find her a role: they already had one exotic Garbo on set; they didn’t need another one. She was lonely, her country was on the brink of war, and she couldn’t get a divorce. She had no friends to speak of — at least until a comedian named Reggie Gardiner took pity on her (I dunno, maybe because she was GORGEOUS), and started taking her around to parties.

At one of these parties, probably feeling out of place because she was allowed to smile and talk with other men, she met famed producer Walter Wanger, who was on the lookout for a small but crucial role in his new film, Algiers. He’d tested 17 “name” actresses, but none of them were quite right. The character needed to be stunning enough to basically switch the entire direction of the plot. But Lamarr — she was the right stuff.

Fast forward to about 1:00, and you’ll see Charles Boyer doing his best Pepe LePew, telling Lamarr, “You’re lovely, you’re marvelous,” and Lamarr’s perfect response. No one is allowed to attempt another eye roll for the rest of cinema. Just exquisite.

And just like that, Lamarr made it, an instant phenomenon of a magnitude unseen since the American debut of Marlene Dietrich. It was like when Natalie Portman first blew everyone away in The Professional, or how Kate Hudson slide around to “Tiny Dancer” in Almost Famous — before, there was an actress; then, suddenly, there was a glittering, unquestionable star.

Post-Algiers, MGM was on it. The fan magazines were instantly awash in Hedy profiles, each organized around five main points, recycled and reiterated for good measure:

1.) Hedy was Glamorous. That’s because she’s European, and used to be very rich, and had a last name that worked very well as the pun “Hedy Glam-ar.” She even smoked glamorously, “something princess-like, like a high-born lady in an exclusive spot on the Riviera.” And with glamour came traditional values: a man’s job was to bring gifts and provide; a woman’s was to be charming and be, well, a woman. She insisted that her favorite perfume was at her bedside every morning, so that she could immediately touch her mouth and brows with it upon waking. If she didn’t, the day started all wrong and never “comes right.” She wore makeup to bed, because that was when a woman should be her most attractive, and wouldn’t speak to a man if he hadn’t shaved. Or so the fan magazines said.

2.) Hedy was Beautiful. She was “Vienna’s Gift to Men” and “Every Wife’s Phantom Rival.” She was so beautiful — and so traditional — that she made “women exciting to themselves again” because, according to one totally horrible fan magazine writer, all the progress of the New Woman had basically made all women into dumpy, independent, flat-sole-shoe wearing bores who spend way too much time wearing “man-tailored suits,” splitting checks, and “rubbing elbows” with men at the workplace. Women had forgotten the allure of lace and veils, of “spangled fans and beauty spots and lovers who die for us.” But Hedy! She made women remember.

3.) Hedy was no Fascist. In fact, she so hated Fascists that she escaped from her Evil Husband who kept her locked in the Evil Castle so that she could survive as the One Hope of Democracy. Or something along those lines, with much purpler prose — “the beautiful bird had fled the jewel-encrusted cage,” etc. etc.

4.) Hedy was no Cheater. Sure, she wasn’t technically divorced. Sure, she was dating Reggie Gardner. But her husband was a Nazi and locked her up, so all was forgiven.

And most importantly,

5.) Hedy was no Ecstasy Girl. To Hollywood Magazine: “I was ver-ee young. They did not tell me what I had to do until after the picture had started.” To Motion Picture: “I was 16. I was so anxious to get a break, I didn’t look at what I signed.” She hadn’t the “faintest idea” that anyone would think it was “naughty”; she was “tortured with shame”; she thought too much had been made of it — “it’s just a lot of chi chi.” Same argument, different tactics: that was the old Hedy, this was the new.

All of this was very pat, very polished fan mag discourse. And it kinda makes me dislike Lamarr — and that might last, were it not for the truly odd details that managed to fight their way through the banal image formation.

Lamarr’s body was European, broad-shouldered, and flat-chested, but by no means big. But she was too big for Hollywood, and MGM periodically forced her to “reduce” for a role. But Lamarr loved to talk about how ridiculous it all was. She told one fan magazine that she just hated the way that dieting women talked nonstop about dieting; when she had to diet, instead of becoming insufferable, she would just lay in bed for four days until the entire ordeal was over.

Too much dieting talk.Then there was this gem of an anecdote:

I love cheese cake. I love to go to the ice-box and eat and eat. But I am on diet; I can’t. One day I said to my companion, “Please lock that ice-box and keep the key.” She did. But one night, after I came home from a party, I was so hungry, I woke her up, took the key, opened the ice-box and went to town, as you say.

HEDY! That is me in every frat house kitchen on campus from the years 1999 to 2003! When she went to parties, she had milk or tomato juice. And she just loved a Drive-In Burger. She was also outspoken and a bit of a loose cannon — so much so that MGM would periodically sequester her from the gossip press entirely, lest she let something slip about the studio’s mismanagement of her career.

Was Lamarr the lady who slept in makeup and hated feminism, or was she the 1930s version of Tina Fey with her predilection towards Sabor de Soledad? I mean, I’m going for the latter, but MGM, obviously, was not. They wanted a glamour girl — someone who could take the place of Joan Crawford, whose appeal was fading, or Garbo, who was basically retired. Lamar was a foil for their newest discovery, Lana Turner — the exotic darkness to her light Americanness.

The problem, however, was that Lamarr couldn’t really act. Or, more precisely, she was what we’d now call a “limited” actress. Even after the success of Algiers, MGM couldn’t quite find the right part. As she told Photoplay, she was getting impatient with the studio’s inability to find her work, even threatening, in the magazine’s pages, to tell gossip columnist Jimmie Fiddler. So MGM put her in I Take This Woman opposite Spencer Tracy, with Dietrich’s longtime svengali, Josef von Sternberg, as director.

It should’ve worked: Sternberg could speak German to get a performance he wanted out of Lamarr, and Lamarr had been heralded as Dietrich’s successor. But Sternberg was also a notorious pain in the ass, and MGM replaced him just weeks into principal photography. Plus, Lamarr was supposed to vamp up Tracy’s character, a benevolent, well-meaning doctor who gives up his work with the poor for a fancy-pants job to pay for Lamarr’s expensive lifestyle. It made Lamarr look very glamorous, but it also made her somewhat unlikable. It was a disaster — even after the new director reshot almost all of the film, MGM knew it was a stinker, and shelved it indefinitely.

The press, though, already knew all about it. Luckily, Lamarr was providing her own personal drama, and as all followers of gossip know, a star’s luster is based less on the quality of her performances and more on the quality, and potency, of the gossip about her.

Because just when you thought you couldn’t get better than a Fascist munitions-trading husband, you get a classic Hollywood love triangle — or, more precisely, a hexagon. It went something like this:

When Lamarr first starting getting press for Algiers, MGM tried to get her to break up with Reggie Gardiner. They didn’t want her with anyone, let alone a schlubby comedian, lest it lessen her allure. But Lamarr refused; she even let Gardiner gift her with a $5,000 pool, which is today’s equivalent of buying a minor celebrity a major condo.

But one night, Walter Wanger (the producer who had put Lamarr in Algiers) invited her and Gardiner to a night on the town. Wanger’s date was the recently divorced Joan Bennett; their romance had been percolating in the gossip columns for some time.

Joan Bennett, in between husbands.At the nightclub, a handsome man came up to greet Bennett. They seemed to know each other well. Bennett introduced him to the table; he was charming and handsome and lovely. The man leaves, and Lamarr asked Bennett, in front of her boyfriend, who that handsome man could possibly be. It was, naturally, Bennett’s ex-husband, Gene Markey — a producer at 20th Century Fox and general man about town. Lamarr’s response: “No! You did not give up such a man!”

She said this in front of her boyfriend! HEDY!

The next day, Markey was over at Bennett’s house, just chillin’ and hanging out with their baby, even though they were divorced. It had been an amicable break-up: they’d been married about five years, and had ended the marriage because, according to Bennett, they’d simply grown incompatible. But no hard feelings! Especially since Wanger was clearly waiting in the wings.

But people were still gunning for a reconciliation: months before the Lamarr encounter, Hedda Hopper had reported that Bennett and Markey might be getting back together. (Think the Twi-hards working really hard to believe that KStew and RPattz will eventually right their wrongs and see the light, but in the 1930s.)

So Bennett, in typical Queen Bee fashion, tells Markey, “You certainly made a hit with that Lamarr girl last night — she said you were the most fascinating man she had ever met.” But Markey plays it cool, hangs out with the kid, whiskey in hand or whatever, and doesn’t rise to Bennett’s bait.

But then Wanger does something devious. He’s producing a new film, Trade Winds, with Joan Bennett in the leading role. And he has Bennett dye her blonde hair black, styling it with center part and loose curls… which makes her look exactly like…

…HEDY LAMARR.

I can’t. I can’t even. It’s just too good. It’d be like Jennifer Aniston dying her hair Angelina brown and taking up the task of world peace. But it gets better, because amidst the gossip press crowing about Bennett’s new resemblance to Lamarr, Lamarr accidentally lets it slip to a gossip columnist that she’s “considering marrying Gene Markey,” also known as Bennett’s ex-husband.

It’s like reality television, only CLASSIER.

The details of the Lamarr-Markey pairing slowly came into focus: turns out Lamarr’s comedian boyfriend had an inconvenient wife back in Britain. They’d been estranged, but no matter — he’d essentially been committing adultery, and MGM wanted none of it. Or maybe Lamarr wanted none of it, and all of Markey. Either way, Gardiner takes a quick exit, Markey enters the picture, and three weeks later, Lamarr’s dropping gossip bombs.

But it wasn’t all for show: a month later, the 23-year-old Lamarr and the 44-year-old Markey were married, and six months later, they adopted a baby boy. Even though the first congratulations on their wedding were purported to come from Joan Bennett herself, the fan magazines loved a feud — in November 1939, months after the wedding, Photoplay ran a four-page spread on “HEDY LAMARR VS. JOAN BENNETT (AND OTHER DANGEROUS HOLLYWOOD FEUDS).”

But Lamarr had other things to worry about — namely, her flailing career. After the disaster of I Take This Woman, and Lamarr’s outspoken criticism of MGM, the studio worked to get her in line, planting bits in the gossip column. She was lazy; she lacked energy. According to the fitting girls on the MGM lot, they’d never seen a star who complained as much — I mean, she wouldn’t even stand for fittings.

It’s unclear whether Lamarr was actually uncooperative or just adamant in her quest for a proper role, but her next film, Lady of the Tropics, set the tone for the rest of Lamarr’s Hollywood career: a high class, exotic, yet slightly whorish woman who was also “mixed race” and wore things like this:

According to film historian Jan Horak, this image was all Louis B. Mayer’s doing: having appeared in the nude as a 16-year-old girl, Lamarr was, at least in Mayer’s mind, forever marked as a whore. Tropics was a bomb, and Lamarr had to fight Mayer for fourth billing in Boom Town alongside Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, and Claudette Colbert, followed by Comrade X, both big enough hits to anchor Lamarr’s career.

The next year, she was very much on image as an adulterous Viennese refugee in Come Live With Me (1940), but the film flopped, and Lamarr had to appeal to Mayer once again for third billing in Ziegfeld Girl alongside a very gamine Judy Garland, a very loose Lana Turner, and a very Jimmy Stewart-y Jimmy Stewart.

I have some weird love for this movie, in part because Garland is just so hilariously out of place between Lamarr’s marble cool and Turner’s sloppy, tipsy, flirtation. And the outfits, well, they can speak for themselves.

Lamarr’s character is once again slightly adulterous, but is also slightly still in love with her virtuous violinist husband. She’s also curiously unemotive — a blank slate of beauty. Not that that was necessarily something new: in publicity photos, she was never allowed to smile; she told one writer that since her father’s death, and her husband’s refusal to allow her to show joy, she simply couldn’t. But it also gave her a coldness — which, coupled with the fan magazines’ insistence that she was out to steal your husband, made her difficult to like.

Even when she divorced Markey and endured a prolonged fight to keep their adopted son, she was still playing “the other woman” onscreen. In one of her most successful films, White Cargo (1943), she dons what can only be called bronze face to play, according to one description, “a native tramp whose shenanigans stir up plenty of tropical trouble.” In other words, she sleeps with every European man on an African rubber plantation until she drives them all crazy.

Warner Bros. wanted her for the Ingrid Bergman part in Casablanca, but Mayer refused to lend her, only to change his mind for The Conspirators, which is basically Casablanca with slightly different locations and plot points, even down to the casting of Paul Henreid. But it’s got Lamarr in this headdress, so I can get behind it:

And then, a gradual decline. Lamarr married British actor John Loder in 1943, had two children, and left MGM. She founded her own production company; she worked with a string of B-list co-producers. She tried to do something different than what MGM had made her into. Like Lana Turner, she probably would’ve been superb as an unrepentant femme fatale, but she kept trying to be a cross between the sexual and the submissive, the independent and the domestic.

Only by returning to her image as a wanton, exotic, barely clothed temptress — in Cecil B. Demille’s Samson and Delilah — did she reinvigorate her career.

Girl is 36 years old here — and she is looking fine. And DeMille knew it, which is why she appeared, decolletage in prime display, on the cover of Newsweek in the weeks leading up to the film’s release. It was the exotic, hyper-sexualized Ecstasy Girl all over again, down to the orgasmic look she gives as she grabs Samson’s pecs in the storied chariot-racing scene.

Samson and Delilah became the highest grossing film of 1949, but it also proved to be Lamarr’s swan song. A string of subsequent films couldn’t sustain her comeback, and like so many stars from classic Hollywood, she spent time on ’50s television, making her final film appearance in 1958.

Lamarr’s story, and its overarching narrative of scandal, didn’t end there. By the late ’60s, she was on her sixth husband, whom she had just divorced when she was arrested for shoplifting in 1966. The charges were dropped, but one of Andy Warhol’s disciples made a film, Hedy Goes Shopping, with a transvestite thoroughly (and very effectively) lampooning her post-filmic career, unfortunate plastic surgery and all.

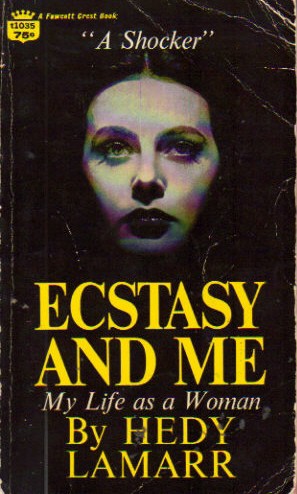

But Lamarr had a much larger problem — namely, the publication of her memoir, Ecstasy and Me.

As the cover announces, Ecstasy and Me was indeed a “shocker,” replete with lurid details of Lamarr’s sex life. She claimed that several parts of the book had been fabricated by her ghostwriter, and sued the publisher for libel in her own memoir.

When the case went to trial, the publisher had an admittedly brilliant (albeit truly abhorrent) defense: Lamarr has, and always has had, a “notoriously bad” reputation for “morality, integrity, and honest dealing.” She was desperate; all she had to sell was her sex life. The judge in the case called the work “filthy, nauseating, and revolting,” but he also ruled against Lamarr. Her enduring image, invoked yet again in the title of the memoir, made it very easy to believe that the contents of the memoir were not libel, but truth.

And so Lamarr retreated to Florida. She became a national punch line — quite literally — with the “Hedley Lamarr” character from Blazing Saddles. In 1991, she was caught shoplifting once again, this time for $20 of eye drops and laxatives.

But Lamarr’s story was, rather ironically, just beginning. Or more precisely, her legacy was about to change as dramatically as any star’s, before or since. Over the course of the next 10 years, she transformed into a symbol of female intelligence, a groundbreaking inventor and a potential genius who was not only responsible for cellular technology, but also democracy as we know it.

The story, beautifully reconstructed by film historian Ruth Barton, goes something like this:

Lamarr had always loved design. She loved inventing things; she was smart and clever and skilled. When she died, she would leave behind designs for all manner of contraptions, including a [sic’d] “functionable, disposable accordion type attachment for and on any size of Kleenex box” as a place to put used tissues, along with a glow-in-the-dark dog collar, an anti-wrinkle technique that operated on the same principles as the accordion, and many more.

But none of that ingenuity and curiosity could be on display — not during her marriage to Mendl, nor during her Hollywood career.

That didn’t stop Lamarr from trying. Back in Austria, various men had met with Mandl to develop an idea for “frequency hopping,” but Mandl got distracted with the war effort and nothing ever came to pass — until, that is, Hedwig Kiesler Markey (alias Hedy Lamarr) and George Antheil filed a patent for it under the name “Secret Communication System.”

Lamarr, it seems, had smuggled the blueprints, or at least the kernel of the idea, back with her to America. During her early days in Hollywood, she found herself at a cocktail party with George Antheil, the oddball Modernist composer. According to Antheil’s equally oddball memoir, Lamarr asked him for advice on how to accentuate her famously small breasts (Antheil’s in-text commentary: “her breasts were fine, too, real postpituitary”), which somehow — I mean seriously, I have no idea how — lead to the discussion of frequency hopping.

Antheil wasn’t that odd of a choice as a collaborator. He’d spend a lot of time fiddling with pianos for his modernist concerts, and he used the technology of two synchronized player pianos transmitting code to flesh out the theory of frequency hopping. Complicated science made simple: they figured out a relatively straightforward way for missiles to go undetected.

You can imagine how valuable this technology would be to World War II America, and how it could’ve potentially made Lamarr into a genuine war hero. And as irreconcilable as this information may have been with Lamarr’s hyper-sexual image, it did not go completely ignored.

A small Motion Picture piece from 1941, suggestively entitled “Hedy’s Secret Weapon,” broke the news that The Ecstasy Girl was also a Girl Inventor: “They say it isn’t right, that it shouldn’t happen. Anyone as fabulously beautiful as Hedy Lamarr simply cannot possess brains!” Yet it was “undeniably true” — Patent Number 2292387 belonged to Lamarr.

Over the course of the two-page feature, Anthiel gives full credit to Lamarr, claiming his work on the patent was merely technical. Motion Picture also touches on the very crux of Lamarr’s problems in Hollywood:

The enigma that is Hedy Lamarr has long puzzled Hollywood. Time after time she has caused studio personnel and writers to scratch their heads in bewilderment. Whether it is quoting Goethe or discovering a new headdress, she is consistently startling those who have just settled down to the idea that she must be another typical beauty with a negligent I.Q.

A woman with brains: just too much for Hollywood, and the appetites it fed, to handle. The Navy found the invention “unworkable” and the story died — or so everyone, including Lamarr, thought. She never spoke publicly of the patent or her other inventions; she failed to even make mention of the work in her memoir.

But in 1973, the founders of the first “National Inventor’s Day” decide they want to drum up a little sexy publicity by issuing a press release with the names of unexpected female inventors. There were women who had come up with ways to make cleaning easier, ways to make cooking faster, and then there was Hedy Lamarr, the woman who had made missiles stealthier. Lamarr was surprised — she didn’t realize the patent had been used for anything — but as it turns out, the technology had been implemented during the Cold War; indeed, it was the threat of these new, untraceable missiles, at least according to lore, that led Kruschev to back down during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Democracy had been saved, and Lamarr — sex pot, shoplifter, crazed aging star — was in no small part responsible.

Still, it wasn’t until 1997 that the story the glamour girl turned inventor really took hold. The Electric Frontier Foundation honored her for her patent, which was also responsible for “spread spectrum” communication technology — in layman’s terms, the stuff that makes mobile phones, Blu-Tooth, and Wi-Fi work. She received a substantial write-up in the Chicago Tribune, and a Canadian company paid her a hefty sum to buy out 49 percent of her interest in the patent in return for the rights to use her image in marketing.

But Lamarr stayed sequestered in her Florida home, allowing her son, Tony Loder (who, in a piece of delicious serendipity, actually worked at a mobile phone company) to be her mouthpiece. She taped a gracious response for her award from the Electric Frontier Foundation, but rumors, wholly unsubstantiated, began to spread that upon learning of the award, she had simply responded, “it’s about time.”

When she died in 2000, at the age of 86, Lamarr was a wealthy woman. But as Barbara Rose argues, it wasn’t until her body disappeared — the persistent reminder of her sexual image, her seemingly uncontrollable urges, the site of her horrible plastic surgery — that her image could be fully recuperated. In 2003, she was the covergirl for Dignifying Science: Stories About Women Scientists. Today, the Austrian prize for inventing is in her name, and her birthday serves as European Inventor’s Day. She’s become the unlikely yet compelling symbol of innovation and design. If people know about her today, it’s not as the Ecstasy Girl, but as the star who made your cell phone possible.

It’s a nice story. It’s certainly what drew me to Lamarr, a star whose significance to film history has become little more than a footnote. And as thrilled as it makes me, as someone who spends most of her day making a case for the cultural and historical importance of stars, to celebrate Lamarr, I’m also super wary of doing so uncritically.

Don’t mistake me: I am all about female scientists, and I’m all about recuperating Lamarr. But sometimes it’s much easier to celebrate the triumph without due attention to the 50 years of sexism that made it so impossible for Lamarr to escape a single “misstep,” made before she was even 20 years old, and the image it would dictate for her.

I’m not suggesting that Lamarr was forced to be a sex symbol. Or maybe I am: the threat of poverty led her to Ecstasy, the threat of capture led her to MGM. And so her beauty, her face, and the way it looked in the throes of pleasure, became her prison.

In her memoir, Lamarr wrote that her face had become her misfortune: “it has attracted six unsuccessful marriage partners. It has attracted all the wrong people into my boudoir and brought me tragedy and heartache for five decades. My face is a mask I cannot remove: I must always live with it. I curse it.”

The face obscured the intelligence, the wit, the desire for something more. It became the synecdoche for her image, the whole of self. And it’s not like we don’t do this to women today: forcefully, if subconsciously, mapping a desired vision of who they are and what they represent from a collection of paparazzi shots, publicity photos, and bad interviews. We do it to the girl who’s by beautiful and by herself at the concert; we do it to the student in our classes with the sorority shirt and the bitchface. I do it to Megan Fox and Olivia Wilde and Kim Kardashian; you may do it to your own slew of beautiful, desirable, and thus easily dismissible women.

Lamarr, with her typical candor, once said that “any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” That which our society values most in a woman — the beautiful, the glamorous, the exotic — are still positioned as mutually exclusive of intelligence, self-determination, and independence. It’s fine to think Lamarr, Female Scientist, is awesome.

All I ask is that you then look at her enduringly unsmiling face, and remember exactly what made it so difficult to live that celebrated life.

Previously: Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Robert Redford, Golden Boy

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.