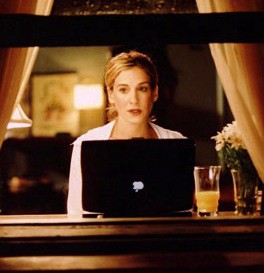

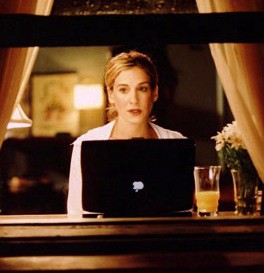

“Don’t worry, it’s no ‘Sex and the City,’ they say. As if that were a good thing.”

At the New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum writes a terrific piece about the retroactive reduction of Sex and the City to a pun-laded guilty pleasure. She defends the show’s place within the canon of complex prestige cable series as well as Carrie Bradshaw’s status as the “unacknowledged first female anti-hero on television,” and reminds us how far away the SATC cast were from the bright-eyed, sweet and manageably tenacious Mary Tyler Moores that had come before them:

Carrie and her friends — Miranda, Samantha, and Charlotte — were odder birds by far, jagged, aggressive, and sometimes frightening figures, like a makeup mirror lit up in neon. They were simultaneously real and abstract, emotionally complex and philosophically stylized. Women identified with them — “I’m a Carrie!” — but then became furious when they showed flaws. And, with the exception of Charlotte (Kristin Davis), men didn’t find them likable: there were endless cruel jokes about Samantha (Kim Cattrall), Miranda (Cynthia Nixon), and Carrie as sluts, man-haters, or gold-diggers. To me, as a single woman, it felt like a definite sign of progress: since the elemental representation of single life at the time was the comic strip “Cathy” (ack! chocolate!), better that one’s life should be viewed as glamorously threatening than as sad and lonely.

Nussbaum also addresses the radical and welcome way that Sex and the City refused to equate love with redemption: “Big wasn’t there to rescue Carrie,” she writes. “Instead, his ‘great love’ was a slow poisoning.” Carrie found love and turned into a poseur, and even positive change rarely came neatly: “During six seasons, Carrie changed, as anyone might from thirty-two to thirty-eight, and not always in positive ways. She got more honest and more responsible; she became a saner girlfriend. But she also became scarred, prissier, strikingly gun-shy — and, finally, she panicked at the question of what it would mean to be an older single woman.”

So why is the show so often portrayed as a set of empty, static cartoons, an embarrassment to womankind? It’s a classic misunderstanding, I think, stemming from an unexamined hierarchy: the assumption that anything stylized (or formulaic, or pleasurable, or funny, or feminine, or explicit about sex rather than about violence, or made collaboratively) must be inferior. Certainly, the show’s formula was strict: usually four plots — two deep, two shallow — linked by Carrie’s voice-over. The B plots generally involved one of the non-Carrie women getting laid; these slapstick sequences were crucial to the show’s rude rhythms, interjecting energy and rupturing anything sentimental. (It’s one reason those bowdlerized reruns on E! are such a crime: with the literal and figurative fucks edited out, the show is a rom-com.)

Most unusually, the characters themselves were symbolic. As I’ve written elsewhere — and argued, often drunkenly, at cocktail parties — the four friends operated as near-allegorical figures, pegged to contemporary debates about women’s lives, mapped along three overlapping continuums. The first was emotional: Carrie and Charlotte were romantics; Miranda and Samantha were cynics. The second was ideological: Miranda and Carrie were second-wave feminists, who believed in egalitarianism; Charlotte and Samantha were third-wave feminists, focussed on exploiting the power of femininity, from opposing angles. The third concerned sex itself. At first, Miranda and Charlotte were prudes, while Samantha and Carrie were libertines. Unsettlingly, as the show progressed, Carrie began to glide toward caution, away from freedom, out of fear.

[TNY]