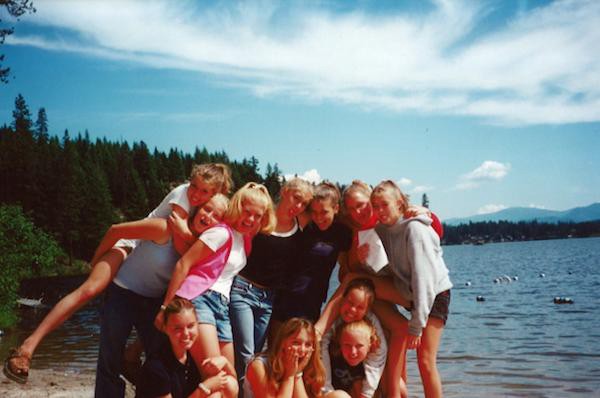

Lord I Lift Your Camp On High

by Anne Helen Petersen

This is the third installment in a series about summer camp.

There was a certain way that the old floating dock looked — the blue stubbled water carpet gradually unraveling, the well-algaed, oil-slick sides, the cracked plastic at its corners — that told me that it was a.) super dangerous and b.) the best, most important thing. You weren’t allowed to go on the floating dock, which the underpaid and overworked lifeguards tethered to the dock with a 50-foot piece of rope, without a counselor until you were 13. I mean, you weren’t allowed to do a lot of things at camp until you were 13 — but once you were, it became a flirtfest of epic proportions.

And by flirtfest, I mean EVERYONE TRY AND RUN TO ONE SIDE so that lots and lots of shrieking and near-falling-off occurred. If you did fall off, you can’t imagine how awkward it was to be hoisted back up or — hell of hells — have to swim back to the main dock and its swarm of less-cools, silently wishing for their own tenure on the floating dock.

The cool boys were skinny and wore long, dripping shorts; the cool girls were well-breasted and wore flattering one pieces. No bikinis: they weren’t allowed. Neither were spaghetti strapped tank tops (“lasagna straps” = OK) midriffs, visible bras, shorts shorter than where your fingers tips naturally fell when placed at your side. Because all of those were “temptations to our Christian Brothers,” who were, if our counselors were to be believed, pulsing lumps of potential masturbation, just waiting to use our bikini-ed, spaghetti-strapped figures as objects of furtive, furious masturbation. They would be sinning, and it would be our fault. Or so the unspoken narrative went.

So much went unspoken at Protestant camp in a small, unpopulated corner of Washington. How to do the motions to “Pharoh, Pharoh,” during song time, how flipping wood chips was the most effective time waster during the quasi-sermon, that Arts & Crafts was only fun the day you did candle-dipping, that the High Ropes Course was, in truth, terrifying. That when you tie-dyed your underwear it wasn’t that cool and it faded after one wash; that the best deal in the camp store were the five-cent red ropes. That your best strategy for survival was to give yourself over entirely to the camp theme and the totally bizarre all-camp games they inspired, even if it meant a.) swimming across half the lake with a ziploc of Velveeta and then eating it; b.) drinking a shake composed of Spam and Clamato; or c.) furiously devouring popsicles made of clam chowder while diligently saving the clams for the most points for your team.

This might all sound absurd, bordering on farcical, but you have to understand that religious camps — and very cheap Christian camps in particular — have no sources of entertainment save praise songs, charismatic counselors who work for free, and overblown, week-long, thematic gimmicks (usually alluding to some very palatable and acceptable pop culture phenomenon, mixed with something gross) to anchor the evening’s activities. I wish I could tell you the themes that incited the activities listed above, but they’re lost: all that matters is that I ate and did gross things for my team, in praise of the Lord.

The cabins were off-kilter, infested with squirrels, and just big enough to fit five bunk beds. The bathhouse was an actual safety hazard, with showers that would issue an electric shock every time you tried to shift the temperature. The lake wasn’t big enough to even use boats with engines. Periodically the kids from “Pioneer Camp,” a somewhat rogue yet affiliated camp down the road, would invade, smelly and swollen from nights spent in teepees, jump in the lake, and retreat to make meals of burnt pancakes over campfires. They operated on “Pioneer Time,” which was another way of saying that they took away everyone’s watches, stayed up late when they felt like it, then slept in until it felt right. It was weirdly progressive and hippy, especially for Presbyterians, but those were the rag-tag kids, the ones with torn shirts they’d been wearing for days. We looked down on them, but they thought we were just ridiculous, with our curling hair in the middle of the woods and dishwashers and windows.

They were right. Because here’s the thing about camp: it’s not supposed to be nice. There aren’t supposed to be luxuries, and I’m not just saying that because I’m a 32-year-old who’d very much like to go back. Even when I was 12, I understood that camp was about doing what you could with what you had, or, rather, what camp let you have: a too-large 100% cotton tank top with the camp’s name in primary colors, Amy Grant’s Christian album, a care package of stale cookies from your friend’s mom, and a week to hang out with boys freely, if chastely, who hadn’t known you for your entire life.

As I grew up, I’d go to bigger, more expensive, highly specific camps: math camp, science camp, French camp, HUGE ASS NERD CAMP. But I always spent at least two weeks at this ramshackle one. Ostensibly, it was camp for God’s sake, but until you got into high school and started using language like “invited Jesus into my heart,” and even afterwards, it was camp for camp’s sake, camp qua camp, with a slight Christ-y inflection that only really came out after sunset.

I think I told myself, and my parents, that I loved camp because I loved Jesus, but I really loved camp because I liked boys, and singing, and routine. Most of all, I loved being a “returning camper,” which is just another way of saying that counselors loved me. For various reasons to do with who I am and what my hometown was, I never felt comfortable in my schools. But camp! At camp everyone is awesome, even if only for a week. I get why people hate camp and, by extension, hate camp people; I understand how and why it can replicate the same social dynamics of home. But in the ill-constructed cabins of my youth, before the camp put in an espresso bar and zip-line and started charging $500 a week, I found a place simple enough to allow for my complications.

I eventually became a counselor at that camp and gradually became disillusioned with the bald-faced manipulation of children’s emotions. When people say camp is like a cult, they’re not wrong. But people are drawn to cults when they’re uneasy with themselves — when they feel like they belong to no one and nowhere. They buy the singing and hand waving, the mystic explanations and cheesy parables, because they elicit the emotions that others expect, and fail to obtain, from day-to-day experience.

That’s what camp did for me: it made me feel. Joy, religious fervor, fear, teenage lust. And everyday that I woke up and lined up with my cabinmates outside the dining hall, creating some nonsensical chant to get into the dining room first, I knew the others were swept away by it as well. Even the kids who thought themselves too cool would, by the end of the second day, find themselves swept up in camp’s idiosyncratic, otherworldly rhythms and modes of behavior. I was more than happy to bend to those rhythms and make them my own. I thought I was proselytizing about Christianity, the grace of God, the release from sin. Really, I was just trying to get people to go to camp with me, where we could reorganize our lives around the floating dock and the boys with the Jonathan Taylor Thomas haircuts from Cabin 5B.

Camp isn’t for everyone. But it was sure as shit for me.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here. Her book, Scandals of Classic Hollywood, is forthcoming from Plume/Penguin in 2014.