When a Girl Becomes a Demon

This is the fourth installment in a series about summer camp.

Round Mountain Camp for Girls collapsed one afternoon in late July, just before dinner, when blood sugar started to drop.

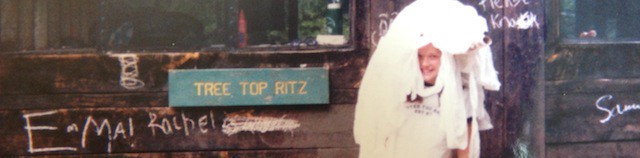

•The first summer, I lived in a cabin called Tree Top Ritz. Our counselor, L., told us scary stories at night and played guitar on a chair in the field between the cabins during her downtime. The other counselors were just as impossibly cool. They wore those fake henna necklaces that we didn’t have yet and they all had Gap sweatshirts, the ones with the big logo on the front. We were fourth graders, I think; they were 15 and 16.

I had never been to a sleepover camp before. I over packed by a month and brought photos of my brothers and stamps so that I could write home, as if I was leaving town for good. Actually, I was going a town over and across a river, about a 20-minute drive from where I lived. My mom drove me, and made my bed, and took a picture of me next to the cabin sign. I have on a one-piece swimsuit and a very deliberate middle part.

That summer we sang songs and played with papier-mâché and learned how to swim backstrokes in a straight line, or close enough. We devised a plan to steal our favorite counselor’s underwear and hang it on the flagpole overnight, and we actually saw it through, giddy in the script-like nature of the prank, not at all embarrassed by it. The next day at morning role call we saluted the flag, and P.’s bra, and burst out in a line of proud giggles. We had a talent show at Hildy Hall. I sang “My Heart Will Go On.”

On the last day, M., the counselor I idolized — she could make the throw from second base to home while also wearing white eyeliner — told my mom that I had “perfect” eyebrows, and when we pulled out of the driveway, I cried.

•

I had ripped out the cover of my mother’s People magazine, featuring the entire roster of the U.S. women’s world cup soccer team, and hung it on the wall in our cabin. We sang the songs around the fire. Maybe we started to feel a little bit silly about painting a log for the final bonfire, but it was tradition by now, it was familiar. A year older, we were more committed to our cliques, though, and more bitterly aware of one other — who’d gotten their braces off, who hadn’t, who had a boyfriend, who didn’t. Cabin houses weren’t merely a matter of pride in the annual scavenger hunt finale; they represented actual, clear social divisions that were to be respected.

Before dessert every night, as the designated cabin cleared the dishes, the rest of us did this odd exercise in which we banged our fists on the table in a set pattern and to a solid beat. I’m sure many camps did this. One-two-three-four, one-two-three-four, one-two — 60-some preteen girls banging the shit out of the table, in unison, at an increasingly frantic pace, louder and louder, silverware jumping, until the canned peaches arrived. Then we’d grab our spoons and act like it never even happened. Adolescent female aggression always had that amnesiac quality — best friends at dinner, enemies by dessert — I just never thought about it having a soundtrack.

I got nonsensically homesick one night and begged for the privilege to call my mom the next day, to plead for her early retrieval. I must have sobbed, but I’m not sure why. What could have felt so wrong? She arrived, an hour later, and packed my things into her car, and drove me back over the river and across the bridge, and stopped for gas. I asked for a Klondike bar and ate it through hot tears. “I want to go back,” I declared, when all I had was a wrapper and sticky fingers, and she drove back and unpacked my things. I survived the week.

•

Suddenly, three summers in, we were mean. There were nine of us in a cabin, and two were sisters who we didn’t know very well. We targeted them from day one. We were to enter middle school in the fall, and now we had our own fake henna chokers. The Gap sweatshirts were passé. T., a girl from another elementary school who was our age, had been named a counselor-in-training and it filled us with a simmering jealousy. She had a posse that we did not like very much at all.

We took it out on the sisters. By the second week they’d moved out of our increasingly hostile bunks, into an empty cabin across the way, which we promptly covered in toilet paper one night. There’s a photo of me posing, a heap of useless toilet paper on my head, after we cleaned it up the next day. I’m smiling. There is nothing as severe as the regret pangs of a former middle school bitch.

We were sentenced to bathroom duty, and the sisters moved back in, and we pretended that we knew how to be kind. On the final day, the increasingly harried counselors set up paint sets and big banners of sheet paper for use in some final event that never got off the ground. We started to paint but soon we’d gotten some on our hands, and soon after we’d gotten some on each other, and at one point T. said something rude but playful to R. and R. dipped her hand in the paint tray and put it right over the front of T.’s white Hanes tank top for men — the style we’d learned to call wife-beaters, which we’d just realized were a very cool thing to wear. T. struck back, more violently; she went straight for R.’s freshly-moussed hair, and suddenly it was chaos. There’s an image in my head of R. running across the field at top speed, paint tray at her side and ready to fly, and two single, drawn out syllables: YOOOOU BIIIIIIIITCH! I don’t remember if she really said it, but I wouldn’t be surprised if she did.

The fight escalated quickly. It’s not so much that it turned aggressive; we had been waiting for this moment. Do you have a friend who, when she goes for the playful slap on the arm, always hits you hard instead? We had been in that state, perpetually, for two straight weeks. I am relieved, thinking back on it, that no one had anything resembling a weapon. All we had was paint and hands. So we sort of hit at each other, and some of us threw paint, in a way that was ostensibly playful, but that just as easily have ended in a death. In another photo, S. is reaching out, gripping onto a rival cabin member’s arms. They are locked in the stance, staring at each other through narrowed eyes, and they look like they want to either disembowel one another or burst out laughing.

In the pictures taken after we are standing together but not really smiling. We look frenzied, like we’ve just witnessed something sinister and secret. Half of us are covered, head to toe, in blue and purple paint. We look not unlike pre-teen demons in a low-budget horror flick. The counselors, standing in paralyzed awe from the outskirts of the stained field, ordered us to hit the showers.

That was my last summer across the bridge.