Why Climb?: My Cardio Apostasy

by Nadine Sander-Green

I wake to the familiar smell of yak dung. It’s day 20 of a month-long hike through the Nepalese Himalayas. Bhimsem, my guide, is slurping dahl bat in the teahouse kitchen. He’s anxious to get going, even though we have 14 hours of daylight to trek three miles; the same three miles local children hike twice a day just to get to school. He fidgets with his backpack straps as I eat a chocolate pancake. Then, the speech.

Today we will see many mountains. We will go up. And we will go down. There will be many sights. You will take pictures. Yes? Bhimsem is frustrated when I take pictures of chubby children instead of the tallest mountains in the world. He has been on this hike dozens of times and knows what you are supposed to photograph. Off we trudge down the trail; me, constipated from my diet of snickers bars and instant coffee, Bhimsem, glancing back minute to make sure I don’t disappear. I think about the same things as always: How much battery is left on my iPod, how much money is left in my bank account, if you can vomit from altitude sickness, if Bhimsen is bored, when we would stop hiking that day, when we would stop hiking all together. We arrive at the next teahouse before noon. I spend the afternoon lying in bed, working up the courage to dump a bucket of cold water over my head: my weekly shower. We eat dinner, drink lemon tea and because there is nothing left do to, try to fall asleep at 7:30. I pee in the hole in the ground three times during the night. Then the routine starts again.

I went hiking in Nepal last spring to solve all my problems. I wasn’t expecting some sort of spiritual awakening, I believe in ouija boards and tarot cards but a full blown “awakening” was too far out for me. I did, though, assume time away from regular life in Canada would allow me to gather my pieces and make sense of them. I needed objectivity, to see my life from across the globe. I had retired from life as a daily newspaper reporter: a poor career choice for someone terrified of conflict. And I had just emerged from my first, dark winter in the Yukon. The only time my skin felt sunlight was running from the Whitehorse Star office to my Honda civic, which wouldn’t start because it was -40 degrees and I forgot to plug in the block heater. I bought a flight to Nepal on one of the darkest days of winter and instantly felt better. Hiking, yes, hiking. Hiking would give me the time and space to figure everything out.

Growing up, my family lived in spandex. My mother was an olympic cross-country skier (although she became sick just after I was born), and my three siblings spent their adolescence wearing heart rate monitors and carb loading before the big race. Dad — or Bill — was the coach. They had matching outfits (black with orange flames) that Bill wore as he strolled the aisles of the grocery store after team training. His ski boots clacked on the laminate floor as he chucked four-liter jugs of milk and jumbo-sized Just Right cereal in the cart. Looking good Bill, the man who ran the local Greyhound station told him. My dad blushed and said thank you, though neither of us knew if he was joking.

One day our school went on a field-trip to the ski trails. We were waxing our skis in a little hut when my dad whizzed past the window, icicles growing from his beard. Spandex covered his body like a fresh coat of paint. Guys, check the dude in the flaming suit! a boy in our class said. Everyone stopped and looked out the window. I don’t remember what happened next, only that my face turned hot, and I became aware of how hard it is to shed who you are, and where you came from.

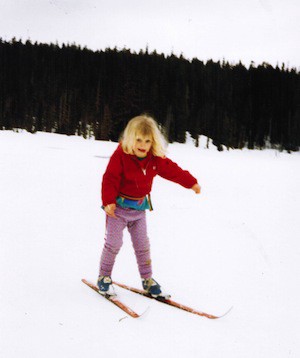

Cardio, it was our religion. I have been skiing and hiking since I learnt to walk. There was no problem that could not be solved by getting that heart rate up. Dad would try to haul us up mountains, or “bag peaks,” by telling us there was a pop machine at the top. We were rarely allowed pop. I daydreamed about pressing every button, giddy with the idea of cold cans of Sprite, Orange Crush, Coke and Dr. Pepper tumbling out of the machine all at once. At the summit I would dangle my feet off a ledge, stare at the jaw-dropping view, unaware it was jaw-dropping because I was five.

One day, driving home from the ski trails, the family crammed in our Mazda Protege as we winded down the mountain road, I swallowed a glob of saliva and said it: I hate this. I would not freeze my toes in ski boots anymore. I refused to slather my body in mosquito repellant and crawl up another mountain, just so I could get to the bottom and say, I was at the top of that. I didn’t get it. Why would you walk all the way up just so you could walk back down? Why did we have to work on the definition in our calf muscles when other children sprawled on their living room carpet, eating Fruit Loops and watching Power Rangers? I thought my parents would be shocked at my dismissal of their religion, but dad just laughed and said Alright, Deenie.

So I stopped. When my family went skiing or hiking I practiced headstands in the living room. I thought they were idiotic. I found solace in gymnastics class, and later, getting drunk in the bush or playing ouija boards in the cemetery. I felt a tug inside when my family left for the wild, as if there was something I was missing they couldn’t describe to me in words. But it was empowering to refuse something. Every time I said no It felt freedom, like I had taken one step away from my family and one towards Nadine, whoever that was.

I would be lying if I said I still stayed away from those sports, now, in my mid-twenties, surrounded by mountains, by people who refuse to breath anything but fresh air. I wouldn’t know how. It’s what you do when you live in these tiny mountain communities. Either that or work on your truck. But do I hike and ski because it’s what I should be doing? On this pursuit of being a wholesome being — ingrained into the psyche of any child raised on homemade yogurt and cooperative games — they seem like worthy activities. Endorphins are great. Being in the natural world heals something inside of you; the trees and streams bring a stillness that is hard to find anywhere else. But every time I climb into my khaki hiking pants and look in the mirror, I feel like a fraud. I know I will spend more time thinking about the same things as always — men, what to make for dinner, how to find something useful to do in this world — than identifying the different types of trees on the trail.

Hiking amongst the world’s tallest peaks in Nepal was beautiful, and meditative, and spiritual in some way. Or was it? That’s what I was searching for, and when I look back at photos it’s what I believe. I miss the enormity of landscape. The children mumbling namaste. The ease of lifestyle. My memories of Nepal are parallel to what I imagined the country to be before I left Canada. I captured what I thought Nepal was supposed to be — children with dirt on their face, landscapes so stunning your Facebook friends want to quit their jobs. But if I really look back, to every hour of every day, I spent most of the time concentrating on a dirt path to avoid soft mounds of donkey shit. I did not solve any problems. I was thinking too intensely about whether I would solve them or not to actually make any changes. I know now beautiful views and carved leg muscles do not heal you. They are the stuff on the surface.

We all have different reasons for going outside, and it’s a difficult to argue against venturing into the wild. It makes us feel good, and isn’t that what it’s all about? Sometimes, though, I wonder about the intensity of it all, if the scrambling is worth it; why we go up the mountain just to go back down. Maybe my childhood philosophy had some weight to it.

Maybe we could just lie down in the woods and stare at the clouds, and that would be just fine.

Previously: Confessions of a Yukon Arm Wrestling Champion, Women’s Division

Nadine Sander-Green lives in Whitehorse, Yukon, a town in Northern Canada where long underwear and gumboots are always in fashion. You can email her at [email protected], or follow her on twitter @nsandergreen.