No Theoryheads Allowed: My 2000s & Wayne Koestenbaum

by Anne Helen Petersen

During the awkward first days of grad school, the institution sent in one of the third-year students to make us feel comfortable in our new environment. In truth, they made us feel fearful of our station in life. Take the first question one asked me, for example: “So are you a theoryhead?”

Blank stare. I think I thought he was referring to a new David Lynch film? I gulped my glass of bad grad reception Chardonnay like a doofus and dodged the question, but its relevance would soon become clear. Humanities grad school is replete with so-called theoryheads — students, mostly dudes, who love to speak as unintelligently as possible and lord their affection for dead and living white guys who’ve done the same over them. And they are, almost to the person, the fucking worst.

To be fair, I hadn’t been educationally reared in the theory tradition. My background was all formalism and historicism, which is another way of saying that my undergrad professors had taught me to “close read” a film and figure out the historical things that made it what it was, but steered clear of theory. This meant that in my first weeks of grad school, I was making serious frenemies of Althusser, Lacan, and Derrida, whose French punning scarred me so badly that I shamefully still can’t return to it. Non-theoryhead-cheatsheet: these were guys who wrote about a.) how society works and/ or b.) how our own psychology/ subjectivity works.

I hated it. Not because it was hard, per se (I’d loved Calculus 3, and that was hard), but because it all seemed so knotted, esoteric, masculine. It felt like every guy who’d ever mansplained me, only he was French and using words that no one — not even SAT tests — ever used. It was Your Dad Talking About Investments + Your Boyfriend Talking About Fantasy Baseball to Your Friend’s Husband Explaining How Arcade Fire is the Linchpin of Modern Rock power.

To answer that third-year’s question: clearly, no, I was not a theoryhead. I wanted to bash my head against my theory book and go back to actually consuming the culture to which these dudes’ theory was deemed so critical in unlocking. Part of the problem was the syllabus (according to this list, apparently no non-white, non-Western non-dude dude had ever “theorized” anythin) and part of it was the teacher, and my lack of experience, and general first-year paralysis.

Thanks to the books of my academic forever-boyfriend, Richard Dyer, I figured out that theory could not only be directly and productively applied to things that I love (specifically: Hollywood stars) but that it could also be intelligible, coherent, even accessible. But it’s no coincidence that the professors who made theory make sense were a mix of women and queer men — academics with no vested interest in upholding the dominance of inaccessible, super masculine, theoryhead men in the academy. In short order, I fell for Barthes, rethought my position on Althusser, and found myself enthralled by Julia Kristeva, the sole female voice amongst the French Dude Club, with her bewitching theories of abjection, e.g. the things we label, as a society, as gross and undesirable. Now I even teach the theory class to my undergrads — in a way, I like to think, that makes theory less of a thing to be a stiff, pompous “head” about and more of something curious and compelling, a tool to unpack rather than a mallet to pound.

Which doesn’t mean that I’m not still terrified of it. But this has been my six-paragraph way of saying that I finally found someone who makes me less so, who makes theory come alive within his pages, whose explanation didn’t make me feel stupid so much as hungry and satiated at the same time.

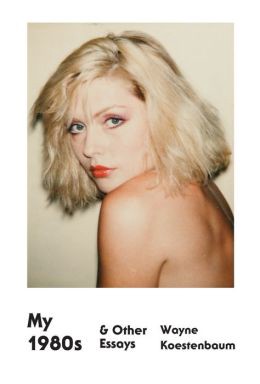

This author, Wayne Koestenbaum, and his new collection, My 1980s and Other Essays, might not be for everyone. He’s written a billion books and seems cool and gay and New York in that way that is, at least on its surface, super intimidating. He writes about opera and classic film stars and porn and Debbie Harry, amongst many, many other things, much of it interwoven with theory. But a theoryhead he is not: his writing is pungent, replete, intoxicating, infectious. I read it and I want to make it my own, to steal his precision and lyricism and immaculate means of evoking the spectacularly specific. I love his clipped paragraphs, which makes you wonder why anyone ever needed a long one; I love his raunchy, unembarrassed confessions laid alongside descriptions of high art. It’s not high meets low, exactly, so much as the experienced meets the abstract.

If you’ve never encountered any of thinkers Koestenbaum references, your reading might not be as lush, but it also won’t be lost. Take his essay on Susan Sontag (most famous for “Notes on Camp”) which starts with the line “Susan Sontag, my prose’s prime mover, ate the world.”

It sounds a bit sexy, if obscure, but then he continues with this:

“In 1963, on the subject of Sartre’s Saint Genet (her finest ideas occasionally hinged on gay men), she wrote, ‘Corresponding to the primitive rite of anthropophagy, the eating of human beings, the philosophical rite of cosmophagy, the eating of the world.” Cosmophagic, Sontag gobbled up sensations, genres, concepts. She swallowed political and aesthetics movements. She devoured roles: diplomat, filmmaker, scourge, novelist, gadfly, essayist, night owl, bibliophile, cineaste . . . She tried to prove how much a human life — a writer’s life — could include.”

You don’t really need to know who Sartre, Saint Genet, or even Sontag is in order to understand what he’s going to show you about her — that she was a writer who harnessed the world differently, and that model is the one that Koestenbaum has aimed to emulate. The rest of the essay continues apace, ending with this delicious appreciation: “Sentence maven, she enmeshes me still: in her prose’s hands I’m a prisoner of desire, yearning for a literary art that knows no distinction between captive and captor. Such art can be sadomasochistic in its charm, its coldness, its vulnerability.”

If you haven’t experienced Sontag, don’t you want to now? Is that not the purpose of criticism? She may not power you as she powers Koestenbaum — I like her fine, but don’t hold the same love — but having read this essay, I appreciate and understand her differently.

And then there’s the beautiful things he says about Roland Barthes, a theorist whose elegance has always enchanted me. There’s a short essay by Barthes in his famous Mythologies collection entitled “The Face of Garbo,” and reading it was the first time I understood what it meant to be simultaneously totally drawn to a piece of writing and utterly confused by it. Having now read that essay at least 20 times — it’s only four pages — you’d think I might grasp it, and the theory that undergirds it, a bit more. Not really. But then there’s Koestenbaum with this:

“Barthes had one lifelong mission, a messianic thread that connects his disparate ventures into the analysis of fashions, texts, and temperaments: the fight against received wisdom, obviousness, stereotype. (And yet: he would have frowned upon the agonistic machismo of the word fight.) His gentle mission was to rescue nuance. What is nuance? Anything that caught Barthes’s eye. Anything that aroused him. Nuance — a shimmer between good and evil, beyond detection, beyond system — enjoys the privileges of satiated passivity: it never combusts.”

The confabulation of intense words might be off-putting if it didn’t make so much sense. This isn’t Koestenbaum trying to win the jargon-big-dick-off: it’s him using precision to get at an elusive subject: the guiding force of Barthes’ broad catalogue of work. Over the course of the essay, Koestenbaum makes that argument so convincing that I’ll never be able to read, or teach, Barthes the same way again: nuance becomes the theme with which I start and end the conversation.

Again, you don’t have to have read Barthes — and certainly not all of Barthes — to appreciate this essay. But it will make you want to, to witness that particular nuance for yourself, and anyone who can make you want to read a decades-dead Frenchmen who primarily wrote in riddles, bravo infuckingdeed.

Koestenbaum can be playful, as he is in “Cary Grant Nude,” or roving between the personal and the poetic, as he does in “Privacy in the Films of Lana Turner.” He can be weird and experimental, he can throw you out of the essay. Sometimes I turned the page bewildered, others I turned it in rapture. This collection is by no means perfect. Its unevenness — the way it spans form and style, the way it alternately succeeds brilliantly and fails beautifully — is part of its charm.

I found him most powerful in his near-academic treatment of the poetry of James Schuyler, whose work I had read only skimmingly, but with whom I am now apparently deeply in love. The essay is academic merely in the way it takes poems, dismantles them, and shows you how to fall for them, but that’s just the skeleton. The muscle of the essay is its meditation on the way form unfolds, particularly in the work of Schuyler:

“Stopping and starting: poetry’s favorite device is the line break, which prose shuns. At the line break, the poem engages in self-regard, echo, hesitation; it eddies. A prose reader begins to fall asleep; a poetry-lover feels a rising blush.”

It’s a romantic way to talk about poetry, but shouldn’t that be the way to talk about it? Can’t the analysis be as lyrical as the work? Must academic criticism be dour?

Clearly, no. I’ve just been reading the stuff that has been. Theory isn’t bad. Theory is great! It’s what we do with it — like letting it become our identity, our pleasure, instead of the meaning it liberates — that’s dangerous. For me, that’s a lesson 10 years in the making, but Koestenbaum sealed it.

I realize Koestenbaum isn’t the final word on Barthes, Sontag, Schyuler, or anything else. The exquisite and heartening thing about his work, however, is that he’s not trying to be. Ultimately, Koestenbaum’s writing is at once a tribute to these artists’ work and a key to unlock it — and insodoing, feel invited to make your own. I can think of no higher praise.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.