The Beauty Bridge

My best girl friend in the Peace Corps was an energetic, super-hot French whirl of a person who spoke five languages, taught me how to make pie crust and wore consistently excellent winged eyeliner even as we fended off wild dogs and pooped in the woods. One day I was poking around her room and opened a drawer that sprang forth with colorful, lacy, perfectly kept bras. “How many of these did you bring?” I asked her. She shrugged and said a dozen or something. I thought about my own suitcase and told her that I’d maybe brought like a couple bras, a couple sports bras too?

“For two years?” she said, genuinely and innocently surprised. I felt ashamed, but only vaguely. Those were gross times in general, and one must always pick and choose one’s areas of interest: fancy underwear will never be up my alley in any sense, so to speak. So it had been a while, let’s say, since my last purchase when I found myself on American Eagle’s lingerie website a few weeks ago, looking to pick up a few clearance bralettes in a pleasingly abrasive shade of lace.

The Aerie brand is aimed at teenagers, but I’ve never stopped shopping there. Occasionally the site website will remind me that I’m not in their main market, especially for the bras I tend to order, which have reviews like This is PERFECT for under your school uniform!! Once I accidentally ordered the wrong style (the “Ella” instead of the “Emma”) and the sculpted padding (“from Perky to Double Whoa”) was fully two inches thick; the reviews, which I checked before returning it, were sprinkled with complaints from girls who had hoped to coax “better cleavage :/” out of their AA chests. So much of teenage girldom is about learning to perform your gender, to exude sex in preparation for having it; it can take much too long before you realize you don’t have to do a thing that you don’t naturally take to, and this website, while cheery and non-sensational, will sometimes give me a bit of weird.

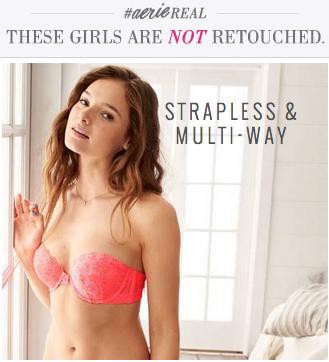

Like the image to the right: it made me feel a little predatory. Stare as close as you want, my friend, these chicks are 100% real. I took a screenshot, filed it away, and then forgot about it until a few days later Jezebel offered money for unretouched photos and featured this exact campaign, saying to Aerie “nicely done.” Then Aerie’s campaign started to get some heat. Adweek called it “revolutionary,” the brand gave a proud statement about “challenging supermodel standards,” and we, the audience, responded: one Refinery29 article on why the campaign is “so important” has almost 50,000 likes on Facebook.

I will probably be buying my underwear from Aerie for the next decade, and it’s lovely to see what they’re doing with stomach texture and slight moves towards diversity. Their campaign is already very successful, and it’s named, simply, “Real.” The Dove version, where women in various iterations are told that they are actually more beautiful than they had suspected, is called “Real Beauty.”

Many people acknowledge that these are just baby steps; nearly everyone calls them a step in the right direction, which they are, but only if we think the best we can do for women is try and shuffle a bunch more of us into “hot” from “not,” if we’d rather constantly redefine beautiful than reject it as one whole gender’s teleology at large.

•••

The way these campaigns use the word “real” here is exactly wrong in an important way, a way that has led to the particular fetish value of the “real” in America. We have a national attraction to authenticity, or the signification of authenticity; we heap enormous amounts of meaning and economic power on things that appear to be whole and true. We authenticate people, too, of course, fussing about whether movie stars, rappers and politicians have an ethos that matches their history that matches their face that matches their words. With women, our attention goes immediately to the body: when a woman is famous enough, her face and figure must be examined for alterations. Remember all that fuss about Britney in her tight white crop top, or Courtney Stodden when she had her brief moment: this authenticity fervor always comes out most strongly when the woman’s body itself is her moneymaker. Searching “Kim Kardashian plastic surgery,” in quotes, pulls up 900,000 hits.

Both Kardashian and Stodden have gone so far as to X-ray their bodies on television, but the desire to expose a non-effortless beauty is pervasive. “Kim Kardashian Needs to Come Clean About Her Surgery,” scolds a headline on a website called CafeMom. This is America; if we’re paying for it, for her — even just with our attention — we want to know that it’s “real.”

•••

In the 1870s, economist David Wells wrote a tract called Robinson Crusoe’s Money, a rewritten narrative in which the natives on Crusoe’s island accidentally discover gold. Recognizing the substance as an “object of universal desire,” they immediately lose their barter economy; gold “acquired spontaneously a universal purchasing power, and from that moment on, became Money.” These natives get along quite well like this until they start printing fiat currency, mistaking paper (the “representative of a thing”) with gold, which is the thing itself.

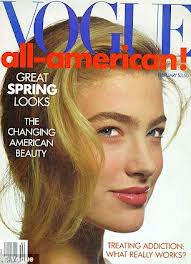

In this framework, gold’s beauty is evidence of its goodness. Its face evinces and is identical to its monetary value; its worth is incontrovertible and fixed. This is the same fantasy we have about the conventional American beauty standard, which shares many qualities with the gold bar: an “all-American beauty” is sleek, blonde, expensive-looking, devoid of complicating layers. We have a fantasy of literal face value, which is why pageants keep trying to force an organic connection between beauty and goodness, why you can pick up a magazine in a checkout line and immediately find before-and-after noses, accusatory arrows, the falseness in every beauty ferreted out.

Historian Walter Benn Michaels wrote about Robinson Crusoe’s Money that its real point is “to show that nothing ever acquires value, that no money can become good and true unless it already is good and true.” This, to me, was the ideological backbone of the Lena Dunham bounty. It is deeply bothersome to us to see women printing money if they don’t have enough gold to back it up. It is disturbing to see women acquiring any sort of beauty-value that their bodies and faces can’t trade on. Dunham’s Vogue photos were fiat currency, divorced from the goods that were supposed to be backing them; they were the representative of the thing, when we were looking for the thing itself.

Now, Aerie is attempting to play their models off as the thing itself. But a campaign about “real girls,” asserting that “the real you is sexy,” hews exactly to the proposition it appears to subvert. I expect that for a long time we will continue to see these baby-soft, often obviously stupid ideas masquerading as empowerment, these ideas that push women around each other on the narrow, precarious beauty bridge rather than suggesting we just howl like animals and jump right off.

•••

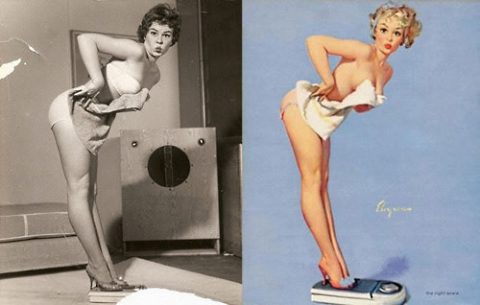

Later in David Wells’s Crusoe, the islanders begin to understand representation and mimesis: they hire an artist to paint “the finest and most fashionable patterns” on a poor person’s clothing, rather than giving the man “real” new clothes. The end result, with “jewelry and fancy buttons to match” looked so much like actual fancy clothing that the islanders happily ran with it, allowing “the shadow of wealth [to] supply the place of its substance.”

To Wells, this storyline provided another argument against the validity of paper currency, whose intentional representation of value was supplanting the accidental representation of value, which “made warfare against the beneficence of the Almighty” and provided for “the survival of the unfittest.”

But why shouldn’t the islanders paint on some buttons? Not everyone’s born rich, born uptown, born to win. I take a lot of personal enjoyment in sometimes using makeup to put a fancy face on my plain face, and that is because I feel comfortable knowing what game I’m playing, and know that I am playing, and by my own criteria, rather than fundamentally attempting to fool. Beauty has always been a matter of where you happen to fall in the cross-section of genes, money, priorities, passing fashions, lasting discriminations; beauty in the twenty-first century can really be boiled down to a combination of technology and time. But we keep effacing this. Like goldbugs, we are seduced by aesthetic pleasure into creating a fantasy of absolute value; we are refusing to recognize the incredible amount of meaning that is constructed in the space between appearance and worth.

Two years ago, the GOP officially considered the possibility of returning the national economy to the gold standard. The fantasy of “certainty, natural law and stable meanings” is as powerful as it is socially bankrupt; on a human scale it walks in lockstep with deep historical prejudice. Beauty, like gold, is valued as we choose to value it. We can print so much more paper, and perhaps just to burn it; there’s no reason not to wildly, transgressively inflate our ideas of beauty, or better yet, cease to care.

•••

When I was Aerie-aged and deeply concerned with what a teenage boy might rate my face and body on a scale from 1 to 10, I was never intimidated by the women I saw in magazines. What cowed me was how tremendously beautiful my friends were. It was a good lesson, maybe, from growing up in Texas: even when girls got plastic surgery or went full All-American, as blonde as can be — some are getting Botox now, at 27! Do your thing, you arrestingly lovely nuts — their “altered” beauty was, to me and to them and to everyone else around us, wholly and powerfully real.

To suggest that there is moral value in accidental beauty because it is accidental is to insist on an essentialism that erases the real complexity of what performing beauty and gender and sexuality means to the millions of people who are invested, for tremendously different reasons, in doing so. Policing and fetishizing authenticity in female beauty is a distraction, a politically blind one when nearly half of transgender people in this country attempt suicide, 87% of LGBTQ homicide victims are people of color, and on and on and on. It is useless to either erase the labor of being beautiful or punish it. The search for the “real” under these definitions will always turn up an answer that is fundamentally meaningless, leaving beauty as the primary mover, chasing turtles all the way down.