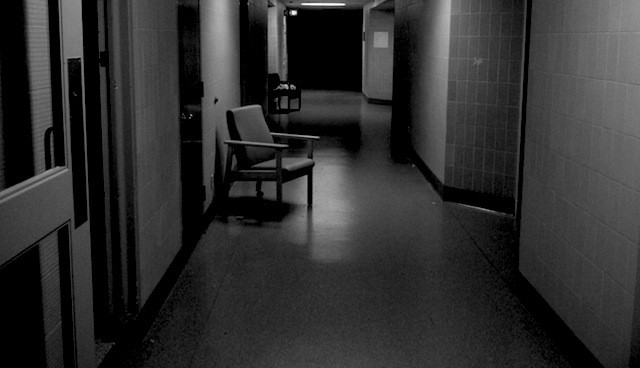

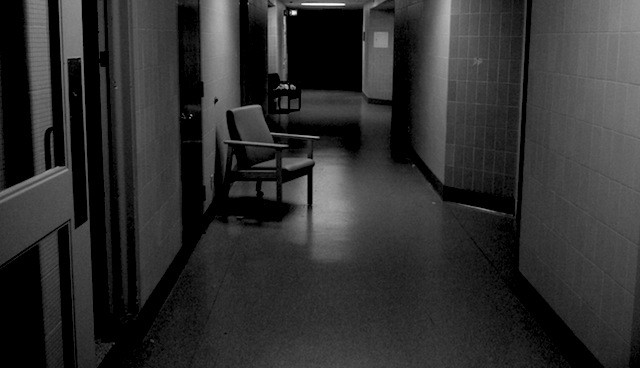

Time Frames

by Brendan O’Connor

The Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey opened in 1937 and closed in 1990. The 600-acre grounds are dotted by Tudor-style “cottages” that housed up to 55 patients each, which are in turn dwarfed by the larger, looming treatment buildings. “This is the kind of place people were talking about when they said someone had been ‘put away,’” Greg Roberts, chief executive at the hospital for 17 years, told the New York Times as he packed up his office. “For a long time, that’s what happened — people were put here and all but forgotten.”

Legend has it that the builders approached the owner of a local slaughterhouse, looking to buy his land. He refused. The hospital was built anyway, the slaughterhouse sitting just at the edge of the property. In later years the bodies of patients who died — or were killed — at the hospital would be disposed of at the slaughterhouse. So they say.

For us, the teenagers who grew up nearby, the place was verifiably haunted. Breaking in became a Monmouth County rite of passage, but it wasn’t until my last year of high school that I would venture onto the grounds. I’d learned of the Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital two years before, when a girl named Olivia asked me on a date. We went to the movies, then drove past the hospital on Newman Springs Road in her old green Mustang listening to Neil Young’s Live Rust while she told me ghost stories.

Two years later, my friends and I were sitting around on a Saturday night wondering what to do with ourselves. I don’t remember whose idea it was to visit the hospital, but then we were piling into my friend Will’s Volvo and driving out into the night. We pulled onto Conover Road and slowed down, looking for the hole in the fence that Will’s older brother had assured us would be there. Just as the car’s headlights passed over the torn chain-link, a black cat leapt out of the neighboring bushes and scampered through the opening. We parked and laughed nervously. Fickle adolescent bravado snuck back into our stomachs as we crossed the street.

“Who has a flashlight?”

Each of us looked at the other. We’d forgotten flashlights. (Of course we had.) No matter, though. It was one of those nights that are very dark and very bright at the same time, the moonlight seeming to come from everywhere and nowhere at once. A thin layer of clouds moved low across the sky, taking their shadows with them as they went. We followed the cat through the fence, but it was nowhere to be found on the other side.

•••

The boundaries at the Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital have always been porous, even before it closed. In 1984, according to the Times, there were 151 reported incidents of patients wandering off the grounds and into the surrounding community. My own mother and uncle — who grew up in the area and attended YMCA Camp Arrowhead across the street during summers — recall camp proceedings occasionally being put into lock-down on account of an escaped patient. In the spring of 1995, William Jennings, who had been found not guilty by reason of insanity in the murder of his parents 15 years earlier, climbed the seven-foot fence and simply walked away. He was found a few days later, 1059 miles away, outside Disney World.

Bored teenagers weren’t the first to sneak onto hospital grounds, either. In February 1987, Democratic state senator Richard J. Codey worked two nights at the hospital after applying for a job using a false identity. “I went to Times Square to get a fake ID,” Codey said. “They wanted $40 on the street. So I went to a shop and got one for $10 that wasn’t very good. But it did the job.” He used the name of a convicted rapist and the Social Security number of an armed robber, both deceased.

Codey’s undercover operation was contemporaneous with an investigation into a series of deaths at state hospitals like Marlboro, including the five patients who died of food poisoning and the 50-year-old woman suffering from cerebral palsy and severe depression who could not feed herself. “When she asked to be fed, she was refused, because her request was viewed by the staff as ‘manipulative,’” the Times reported. “The woman lost weight and became dehydrated in two months and died of pneumonia.”

You can hardly fault anyone for trying to escape such conditions, though life on the outside was not much better even for those lucky enough to be ‘deinstitutionalized.’ Between 1970 and 1978, 14,000 patients were released from state institutions. Many made their way to “the large and once-fashionable hotels and summer boarding houses” of Shore towns like Asbury Park, Long Branch, and Atlantic City. By 1978, officials estimated, discharged patients from Marlboro accounted for 10 percent of Asbury Park’s population; in July 1980, nearby Bradley Beach’s Brinley Inn burned down, killing 23 people — most of them elderly former patients.

•••

The trees fell away as we moved between the empty dormitories. We found ourselves standing on the edge of a wide field of tall grass, roofs rising above the trees across from us. The lights of the single security guard’s car moved up a service road about a half-mile away as we skirted the edge of the field rather than moving through the open.

The hospital’s largest edifices still stood, though barely: the side of one had completely fallen away, exposing a cross-section of the building to the world, something naked and broken and wrong. Abandoned scaffolding hung off its side like half-shed snake skin.

Will wanted to go inside the largest building. He had heard that in some of the offices there were filing cabinets still full of documents — patients’ case-files and such. He wanted a trophy. We opened the front door, peering inside, trying to see through the dark. He took a step forward, and freezing-cold water enveloped his sneaker. He jumped so high he might’ve knocked his head on the ceiling. We decided to come back another night with flashlights, and wandered back outside, where a small graveyard on a hill beckoned.

“I bet there are some people buried here who were executed,” I said. “They definitely used the chair.”

The moon grew brighter, the tombstones glowing through their mossy sheaths as we, a bunch of teenagers — one of us, Will’s twin brother Matt, who should have been there but instead lay in bed at home, sick with cancer — stared and thought about death.

And then, out of the quiet, a snarl like nothing I’ve ever heard before. It was bright enough that any animal large enough to make a sound as loud as that would have been immediately visible. It felt like whatever it was, we were standing right on top of it, but there was nowhere anything could have been hiding.

We ran all the way back to the car.

•••

Matt had been diagnosed the summer before, after suffering a seizure while away at college. A full body scan revealed the germ cell tumor in his chest — a birth defect (an impossibly rare one, too) that went unnoticed until it made itself known.

Matt came home and began treatment at Sloan-Kettering. Will and I travelled into the city every day by train, sometimes talking about Matt, sometimes talking about girls, sometimes not talking at all. Something was happening with the chemicals that were being put into Matt’s body; they reacted poorly with chemicals that were already there. Nobody could say exactly how or why it happened, but for about a month Matt was alternately comatose and psychotic. He suffered vivid, violent hallucinations, sometimes physically struggling against us or the staff, sometimes insisting that we were all in danger.

A little over a month went by, and the madness passed. It was like a fog had lifted, Matt said. He couldn’t remember anything.

For the next two years, Matt subjected himself to all manner of treatment both conventional and experimental. “Just because you’re not going to win the race,” he said, “you don’t stop running.”

I started my first year of college in the second year of Matt’s illness. Sometime over the course of that year, I began mourning his loss, even before he passed. I was in Ohio, and we would talk on the phone occasionally, or more often via Gchat. He was happy for me, excited to hear about the things I was learning and discovering, and every time I went home and I looked in his eyes and something inside me would freeze and drop and shatter.

•••

Marlboro’s demolition was supposed to have begun in 2011 and been completed by 2014, but the project has been delayed due to massive amounts of asbestos in the hospital buildings. They’re still planning to preserve the grounds and turn the property into a park, but not much on the Marlboro grounds has changed since my friends and I were running away from those cracked and crumbling buildings. “It’s going to take time,” said a Department of Treasury spokesman. “No one wants to put a time frame on it.”

Photo via.

Brendan O’Connor is a writer in New York.