Interview With My Mom, The Olympian Who Wasn’t

by Lauren Vespoli

Marathoning the Olympics from my couch, I love seeing athletes experience the games for the first time. So many are ordinary people who have unearthed a real, unique talent and pushed themselves to the brink to get to where they are. They aren’t PR-produced personas, or jaded by years of competition under the public microscope. Many have a sense of wonder and enthusiasm that is simply contagious to their global audience. Take, for instance, 19-year-old U.S. figure skater Jason Brown.

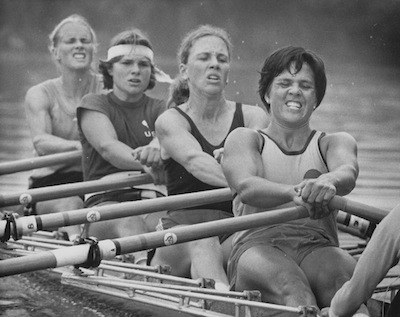

When I watch these ordinary Minnesotans or Bermudians or whomever living their dreams on the Olympic stage, I think of the last Russian Olympics — summer, Moscow, 1980 — where my mother was supposed to compete in the quadruple scull.

Thirty-four years ago, my mother would have been one of those extraordinary, ordinary competitors, a 24-year-old chemical engineer from Connecticut whose coach also happened to be her husband. (Rowing is sort of the reason my family exists: my mom, while training as college rower, met a national team coach whom she began dating. A year after they were married, my father started his own company building boats.)

But the United States — along with 64 other countries — boycotted the 1980 summer Olympics in Moscow in protest of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. So instead of representing the United States of America in the most prestigious athletic contest in the world, she and her teammates were invited to the White House, where they stood in line to shake President Jimmy Carter’s hand.

I couldn’t imagine what that would feel like. So, like a good/nosy daughter, I asked.

First thing’s first: How did Dad end up as your coach? And what was it like to be coached by your husband?

Nancy Vespoli: We got to know each other while I had just started rowing in college, and he said, “You could be as good as these women on the Olympic team.” And I didn’t know why he would think that, but I figured he must know something, because he was a world champion. He gave me workout programs to follow. Then, [after college] when I was in Boston and he was in New Haven, he had showed me how to do the weightlifting and I did that and the water workouts on my own. Then once I moved to New Haven, I worked out at Yale and I would always work out by myself and Dad would come out and coach me on the water.

One time I was crying because he was pushing me to work harder. He just thought I could do it — I don’t know why he thought I could do it, or what makes someone Olympic material, but he just believed it.

In 1979, I rowed the Head of the Charles and he was rowing a single, too, so he rowed with me on the course the week before the race. He didn’t think I was rowing hard enough, and he told me I had to row harder — and I started rowing harder. I think that’s what helped me win it. He pushed me. And he was one of the best coaches in the country, and possibly in the world.

He said “Oh you can do better than these women,” and I just started doing it.

When did you find out that you wouldn’t be going to the Olympics?

The news wasn’t as easy then. The tryouts for the quad, we were staying at Princeton in dorms and there were no TVs. You had to read the paper every day. We were working out two or three times a day, and I didn’t really have time to read the paper. My main focus was on making the team and resting in between workouts. I don’t remember a clear announcement. I kept thinking that maybe they would change their mind or maybe the Soviets would withdraw from Afghanistan.

Being an optimist, I thought maybe it wasn’t really going to happen, but I think it struck me more deeply later in life than it did then. All that work going into making the team, and it was so close to the time of the Olympics that you’re more focused on that.

Later in life you realize that that moment in time, you can’t get back. It’s your age, the amount of time you put in and how much time you have to put into it, and to do that again for another four years wasn’t something I wanted to do. I had just gotten married and gotten a master’s degree in chemical engineering. I wasn’t going to put my life on hold. That was going to be my time. It was just all taken away from you, to have that experience of marching in the opening ceremony. We competed in world championships, but it’s the whole Olympic experience of bringing all the counties and all the sports together, and the whole world is paying attention, and to be a part of that just got taken away.

Wow. How did you balance everything — your marriage, your master’s, your training? Was it ever overwhelming?

No. Well, Dad and I weren’t married until after I got my master’s [in 1979]. I was going back and forth all the time between Boston and New Haven. That’s all I did — I studied, I trained, and I visited Dad. How did I balance it? I got a lot of sleep and I stayed to a strict schedule and I ate well and I didn’t go to any parties or socialize because I was always seeing Dad anyway. I wasn’t going to go out by myself in Boston. I was just focused. They say work expands to the time available, or Dad always says that.

Was that lifestyle ever lonely?

It’s different nowadays because you know who’s around. We didn’t have cell phones so we didn’t have that connection. I didn’t know many people in Boston, and my roommates did different things. I didn’t feel lonely because people didn’t know where everyone was that easily. There was no Facebook, there was no texting or cell phones. No one knew where anybody was. And I’m the kind of person that doesn’t mind being alone. I mean I basically trained by myself, which is unusual.

Do you think it would be possible to balance all of that today?

A lot of the athletes don’t do it, I think. Now they train full-time, but I think it can hurt them in the long run because once they’re done it’s a big hole in their lives. They could go into coaching or something to do with the sport, but if they don’t, what do they do? I think they do a lot more training now and it’s a lot more demanding.

How did you react when you learned you wouldn’t be going to the Olympics?

For some reason I was thinking it couldn’t be real: how can they do that after we put so much work in? I wasn’t thinking about what was right or wrong — we had to do what our president asks us to do.

We ended up going to Europe because we had all these races planned prior to the Olympics. We competed in Germany, Holland and Switzerland. And we did quite well. After our last race before the Olympics, we just came home. In July, we got invited to go to the White House and there were some celebrations at the White House — there was an event on the lawn, and concerts, we had our picture taken on the Capitol steps, the whole Olympic team, and there was a parade. When we were at the White House we got in line to shake hands with the president and Mrs. Carter. Most of my [rowing] teammates didn’t want to do it in protest, but I felt that since we came to the White House we should be respectful. Only two girls on the rowing team and I shook the President’s hand. The other teams didn’t boycott. To me, it didn’t seem right.

Did going to the White House at all make up for the fact that you had been denied a chance to compete in the Olympics?

It was better than not having anything. To be treated like that in Washington and go to the President’s house — those are things we’d never have done otherwise. But it’s not equal to competing in the Olympics, to competing against the best athletes in the world.

Someone told me once what the percentage was of athletes that Moscow was their only Olympics. It was very high. Some people stayed on for another Olympics — some rowing people did but I think a lot of athletes didn’t. There wasn’t as much financial support then, or as much help getting part-time jobs. You couldn’t keep going unless you had some sort of funding or were in a sport the public really cared about.

What would you say to today’s Olympic athletes?

Absorb the whole experience, because you might never have another chance — you could get injured, or something could happen. This is a unique experience that the whole world is interested in, and is probably the only peaceful world event that touches everyone’s interests. It celebrates the human spirit.

Lauren Vespoli lives and writes in New York. She jogs casually and has accepted that this will never make her an Olympic athlete.