After Philomela: A History of Women Whose Tongues Have Been Ripped Out

by Johannah King-Slutzky

The ur-text for women without tongues is Philomela, the princess of Athens famously mutilated by her rapist (Tereus) — who was also her brother in law — when she threatened to name him for his crime. But Philomela is resourceful: still mute, she weaves an incriminating tapestry and sends it to her sister, Procne. In revenge, Procne kills her son and serves him boiled to his rapist-father. When Tereus catches wind of his dinner’s ingredients he chases Procne with an axe, and when Philomela and Procne pray to escape, the gods turn the pair into a nightingale and sparrow. But it gets worse: contrary to Ovid’s interpretation of the myth, whose message is justice, the female nightingale is silent.

So begins a long history of women without tongues. In the Western tradition, tonguelessness is ritualistic and punitive. On women, contemporary modesty is usually a visual category: clothing appropriately fitted, eyes blinkingly demure, etc. But chastity and modesty evolved from the classical Greek virtue of sophrosyne, which is verbal. (Anne Carson translates sophrosyne as “verbal continence.”) Its value is also gendered. Here is how Freud put it: “A thinking man is his own legislator and confessor, and obtains his own absolution, but the woman…does not have the measure of ethics in herself. She can only act if she keeps within the limits of morality, following what society has established as fitting.”

“Tereus Abducts Philomela,” by Johann Wilhelm Baur (c. 1939), via.

This moral deficit is why Timycha, a soldier’s wife in 6th century BCE Greece, would rather tear out her own tongue than be tortured: not because she wanted to minimize her pain, but because she didn’t trust herself, as a woman, to remain silent. Here’s the account as described by Iamblichus’s Life of Pythagoras:

Dionysius therefore, being astonished at this answer, ordered him to be forcibly taken away, but commanded Timycha to be tortured: for he thought, that as she was a woman, pregnant, and deprived of her husband, she would easily tell him what he wanted to know, through fear of the torments. The heroic woman, however, grinding her tongue with her teeth, bit it off, and spit it at the tyrant; evincing by this, that though her sex being vanquished by the torments might be compelled to disclose something which ought to be concealed in silence, yet by the member subservient to the development of it, should be entirely cut off.

As a woman, it’s easier to bite your own tongue off than it is to resist the chatty destiny of your sex, which is easily “vanquished.”

The really fascinating thing about women without tongues is that they’re not followers — at least not straightforwardly. Many of these tongueless women achieve the height of their virtue when they become mute. I mean this in the least analytical way. Not that women are better for their tonguelessness, but that time and again — literally, millennia worth of texts — women earn non-metaphorical immortality by first speaking out and then becoming mute. They also de-tongue themselves as often as they are de-tongued (though always under duress). Tellingly, many of these stories are early versions of fairy tales.

One heroic self-mutilator is Khana, a Bengali folk hero whose weather proverbs are still quoted by the area’s rural population. One Khana saying is “A plentiful crop of mangoes is followed by a good crop of rice and many tamarinds foretell floods.” (This rhymes before translation.) Unlike Timycha, Khana was an unqualified have-it-all. She had a successful career as an astronomer, is credited with building Medieval Bengali language, and she and her husband were in love. One day she presented her findings to the royal court, and the king was so impressed by her scholarship that he called her his “tenth jewel,” the other nine of which were his “nava ratna,” also scholars. The king requested Khana’s presence at the court the next day, but her father in law, Varaha, panicked. Rather than disallow Khana’s immodest presence the next day, he ordered his son to cut off Khana’s tongue. Khana’s husband resisted his father’s demand, but ultimately adhered to patriarchal law and mutilated his wife. In a different version of the story, Khana herself cuts off her tongue, either to spare her father-in-law from upstaging (he was also an astronomer) or, in versions in which her astronomy has advanced to divination, to spare her father-in-law from arrest.

The question of whether these stories are feminist is of some debate in the literary community, particularly when it comes to Shakespearean retellings. Shakespeare wrote at least three times about Philomela mythology: Philomela is Lavinia in Titus Andronicus, Lucrece in “The Rape of Lucrece,” and Imogen in Cymbeline. In Titus Andronicus, Ovid’s myth is explicitly cited and learnt from — when Lavinia’s rapists plan a course of action in the wake of their crime, they elect both to lop off Lavinia’s tongue and her hands to prevent her from tapestry-weaving or any other form of illocutionary revenge. But their plan doesn’t work. Lavinia uses what remains of her limbs to write a message in the forest floor, and her rapists are caught.

In “The Rape of Lucrece,” a long narrative poem, revenge takes a different course. A raped and (bizarrely) guilty Lucrece actually kills herself to encourage retribution, this time at the hand of Collatine, her husband, a Roman leader flanked by Brutus. Although both Titus Andronicus and “The Rape of Lucrece” have been appropriated by feminism, the critic Jane Newman suggests “Lucrece” and other post-Philomela stories are anything but progressive:

Philomela belongs to and represents the countertradition of vengeful and violent women associated with Bacchic legend. This tradition is replete with images of different, more direct forms of political agency for women, images that in fact challenge the fundamental organization and distribution of power in the Western, patriarchal state….[T]his tradition, which materializes onstage in copies of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in both Titus Andronicus and Cymbeline, is also pointedly invoked — but then just as pointedly excised — in and by Shakespeare’s Lucrece.

Although I’ve been talking a lot about ancient Greece, tonguelessness has as much to do with Christianity as it does with the ancient world. How do you go to heaven in Christianity? Some tools are visual or active — the erection of ornate Cathedrals in Catholicism, for example, or the emphasis on actions like baptism, good deeds, and (from God) election. But something consistent to most schools of Christianity is speech — in particular, prayer and confession.

This trope is not specific to women. Men and women who could avow faith in God even when their tongues were cut out were particularly revered. For example, in 484 AD, sixty Christians from Mauritania, a colony off the northern tip of Africa, had their tongues and right hands cut off by Hunneric, a Vandal conqueror famous for his cruelty. Miraculously, the tongueless group continued to speak “as plainly as before.” Pope Gregory the Great called it a miracle, “the most remarkable one on record after apostolic times,” in part because one of the former-mutes had been unable to speak even before the massacre.

“St. Agatha” by Francesco Guarino (c. 1611–1654). St. Agatha’s tongue remained intact, but like the mute St. Christina, her breast was torn off. via.

Although many of Christianity’s tongueless were (male) soldiers, another category of mutes also exists — young female martyrs. One such martyr is St. Christina (so named as a religious permutation of Jane Doe). St. Christina, the daughter of a Roman patrician, was only 11 when this happened:

Urbanus [her father] shut her up in a tower with twelve maids, who were charged to bring her back to the worship of the [Roman] gods. Having no money, she broke her father’s gold and silver idols, and gave the pieces to beggars. Her father therefore ordered her to be beaten and thrown into a dungeon, where angels comforted her and healed her stripes. She was next thrown into the lake with a millstone round her neck. Angels held up the stone, and floated her safe to land. Urbanus had a fire lighted, and put her in it. She remained five days unharmed, singing praises to God. He then had her head shaved, and dragged her to the temple of Apollo, intending to compel her to sacrifice. As soon as she looked upon the statue of the god, it fell down before her, and her father fell dead from wonder and rage. His successor, Julian, heard Christina singing in her prison. He had her tongue cut out, whereupon she sang better than ever. Then he shut her up in a dungeon with serpents, but they could not harm her, so he had her bound to a tree and shot with arrows; and thus she died. [In t]he Spanish version of the story…When Julian had her tongue cut out, she took it and threw it in his face and put out his eye…

Bad ass. It’s hard not to read these Saints’ Lives as anti-patriarchy, especially when the villains are compulsory religion and your father. Other saints’ lives are even more compellingly modern, in that they sound strikingly like Freud’s (sexist) accounts of hysteria, a set of limb-bewitching behaviors historically attributed to Satan. Examples include St. Dominica, who was thrown (by the devil) out of a window, imprisoned, and lost the ability to use her tongue, hands, or feet; and St. Christina (a different one), who suffered suicidal impulses for most of her life (egged on by the devil who appeared to her as St. Bartholomew) and whose symptoms today we might call some combination of conversion disorder and anorexia:

When she was going to eat she saw a toad, a serpent, or a spider on the bread or other food. Her disgust was such that she could not eat. In this way she suffered severely from hunger. A priest, fearing she would die of inanition, advised her to put the food in her mouth, notwithstanding her disgust. As soon as she did so, she felt on her tongue the cold body of a reptile…

Though not a saint’s life, Hans Christen Andersen’s telling of The Little Mermaid also connects tonguelessness with holiness and immortality. Yes: while you may have heard that this early TLM rendition is a touch gorier than the Disney version, what you probably don’t know is that the titular mermaid was (confusingly) dually motivated by love for a hunky prince and a quest for an immortal soul, the latter which mermaids don’t possess. When the little mermaid asks the sea witch for advice, the witch promises to install TLM with a sweet pair of legs — in exchange for the little mermaid’s dulcet voice, which the witch captures materially by way of the mermaid’s tongue. Oh, also TLM will feel like she’s walking on knives every time she uses her legs and will turn into soulless foam if the prince marries anyone else. It’s pretty rough:

“But if you take my voice,” said the little mermaid, “what will be left to me?” “Your lovely form,” the witch told her, “your gliding movements, and your eloquent eyes. With these you can easily enchant a human heart. Well, have you lost your courage? Stick out your little tongue and I shall cut it off.”…”There’s your draught,” said the witch. And she cut off the tongue of the little mermaid, who now was dumb and could neither sing nor talk.

To make a long story short (but really, read it), the little mermaid fails to win the prince’s betrothal and is forced to throw herself into the sea as foam, which is what mermaids become after their typical life span of 300 years. But just before TLM gives herself to the waves, her sisters surface and offer her a second witch-backed trade: if she kills the prince, she can return to her pastoral life as a mermaid princess. The little mermaid, who still loves her prince, refuses, and martyrs herself. But but but: it TURNS OUT that there’s such a thing as air sprites (totally ignored by Andersen until this moment) and they can earn their eternal souls if they perform enough good deeds in a phenomenology suspiciously similar to that of Tinker Bell’s happy laughter/clapping schtick in Peter Pan. Thus, TLM exits the story, if not possessing an eternal soul or a voice, with at least the promise to win the former. Not the tongue, though. That’s just gone.

Etching from Hans Christian Andersen’s Sämtliche Märchen (1873), via.

An even less pleasant fairy tale comes by way of Medeival warfare, specifically as told by The Dream of Maxen, a Welsh “history” which descends from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, the feeder-text for almost 1,000 years of Arthurian legend. In continuing our mythology theme, the story you’re about to read is cousin to old and new classics like The Faerie Queen, The Once and Future King, and Mary Stewart’s excellent Crystal Cave Merlin series. Without further ado, here’s an excerpt from The Dream of Maxen:

The ruler Maxen was Emperor of Rome, and he was handsomer and wiser and better suited to be emperor than any of his predecessors….In his sleep Maxen had a dream. He saw himself travelling to the end of the valley and reaching the highest mountain in the world — it seemed as high as the sky — and having crossed this mountain he saw himself journeying through the flattest and loveliest land that anyone had seen.

Maxen elaborates your typical fairytale quest scenery: beautiful rivers, beautiful fleets, fortresses, etc. Eventually Maxen finds a beautiful castle. Naturally, a beautiful woman presides.

Sitting before him Maxen also saw a girl in a chair of red gold, and looking at the sun at its brightest would be no harder than looking at her beauty: she wore shifts of white silk with red gold fastenings across the breast, and a gold brocade surcoat and mantle, the latter fastened by a brooch of red gold, a hairband with rubies and gems and pearls and imperial stones in alternation, and a belt of red gold. She was the loveliest sight man had ever seen…

Maxen awakes and decides he needs to find his dream girl, so he sends his troops “all over the earth in search of her.” After a while they find her in Caernardon; she is the daughter of a Chieftain. The woman’s name is alternately Elen or Hellen, and she is ~a virgin~. Maxen falls in love with her, and because she’s a virgin, he’s willing to pay top dollar to marry her. He orders three castles for his bride, and busies himself with their building. The whole affair is very time-consuming, and in Maxen’s absence a new emperor takes Rome. So Maxen, who’s no pushover, enlists the help of Elen’s brother, Conanus (Welsh: Kynan Meriadec, French: Conan Meriadoc) and recaptures Rome. That’s where I’ll let The Dream of Maxen resume:

Maxen then said…“Sirs, I have regained control over my empire, and now I will give you this host, that you might conquer any territory you like.” The brothers went out and conquered lands and castles and cities; they killed all the men but left all the women alive, and this continued until the young lads who had come with them were white-haired with the time they had been conquering. Kynan said to his brother Avaon, “Do you want to stay in this land or return to your own country?” Avaon and many of his men decided to go home, but Kynan and another group stayed, and they determined to cut out the tongues of the women, lest their own British language be contaminated.

THE END. Yep! That’s the end of the story, happily ever after. There’s silk, there’s virgins, there’s mountains, and then the men pillage Brittania, murder the land’s husbands, and marry and cut off the women’s tongues to ensure the perpetuation of English among their progeny. It is sooooooo good.

“So they set forth and conquered lands, and castles and cities. And they slew all the men, but the women they kept alive.” Etching from The Mabinogion vol. 2, ed. Owen M. Edwards.

This is probably the only story in my arsenal that doesn’t treat de-tonguing as some kind of punishment. Where the tonguelessness in “Philomela” mixes spite and practicality, Maxen’s tongue-removal process is purely utilitarian (though still symbolic). This is unusual.

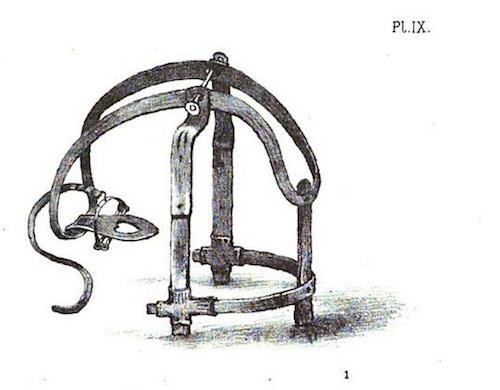

“Brank or Scold’s Bridle” from A Parochial History of St. Mary Bourne, 1888.

By the seventeenth century tongue-torturing women was both less severe and more prolific. For instance, have you ever heard of “the scold’s bridle” or the “brank”? From 1600 to roughly 1850 it was a mask used almost exclusively for the punishment of women. Although there are many permutations of it, as a rule the scold’s bridle is a head-cage with a small piece of metal strapped into the mouth that either bleeds or presses against the tongue to cause physical and symbolic discomfort. The metal projection was usually smooth, its main effect to gag and embarrass, but sometimes the protrusion was spiked. Women were usually treated to the scold’s bridle if they offended their husband or father. But unlike contemporary visions of domestic abuse, this punishment was regulated by court. Here is the earliest known example of scold’s bridle sentencing, from 1614:

Scold. Whereas Ann Walker, daughter of John Walker, of Slaughthwaite, did in the time of ye sessions heare holden, in ye open streets, call one Andrew Shaw ‘cuckoe,’ for prosecuting a bill of indictment on ye King’s behalf against her father. Ordered. That the constable of Wakefield shall cause ye said Ann Walker, for her impudent and bold behavior, to be runge through ye towne of Wakefield with basins before her, as is accustomed for common scoldes.

In an 1858 paper read before the Architectural Archaeological and Historic Society of Chester a man named William Andrews recounts how the scold’s bridle was once used by the town’s “gaoler” and attached to the sides of the town’s older buildings by hook. If a wife was found gossiping, her husband would send for the jailer to bring his bridle and the woman would be chained (by the mouth) to the exterior of her home until she “promised to behave herself.” Says Andrews, “I have seen one of these hooks, and have often heard husbands say to their wives: ‘If you don’t rest with your tongue I’ll send for the bridle and hook you up.’”

It’s remarkable how consistent these millennia of stories are: questionably feminist, instructional, heroic, and always horrifyingly blasé. The plot is the same: find someone who loves you “so much that you meant more to him than his father and mother” (Andersen), leave your home forever, cut out your tongue, dance with “gliding movement” while “every step you take will feel as if you were treading on knife blades,” and sacrifice yourself for God and/or a rich stud. Then you too can be a heroine. If I sound sour, I’m not, really. Because in their quest for goodness, these saints, soldier’s wives, and princesses all experiment with witchiness and defy multiple patriarchal orders to do what they believe is good, which makes the stories significantly more complicated than a streamlined feminism will allow.

Johannah King-Slutzky is a freelance journalist living in New York City. She tweets @jjjjjjjjohannah.