The Engagement Phone Cover and The Wedding-Industrial Complex

by Anne Helen Petersen

Let’s start with some statistics.

Cost of the average American wedding in 2012 = $27,000 (not including Honeymoon).

Cost of the average New York wedding = $65,000.

Median U.S. income = $45,000.

Dollars generated by the wedding industry every year = $30 billion.

That includes dresses, elaborate engagement photos, groomsmen gifts, monogrammed handkerchiefs, signature cocktails, bachelorette parties. The soul/love/capital crushing process has been dubbed the “wedding industrial complex,” a cold term that connotes just how effectively capitalism has insinuated itself in an institution supposedly characterized by love and other priceless emotions.

The wedding industrial complex is not without its detractors: Jezebel has entire category devoted to deriding it (recent headline: “Strapless Wedding Dresses, We Are On to Your Bullshit”); Rebecca Mead wrote a bestselling book, One Perfect Day: The Selling of the American Wedding about it; and dozens of websites (including Offbeat Bride, A Practical Wedding, and the now-defunct Indiebride) offer alternative — and significantly less expensive — routes to wedded bliss.

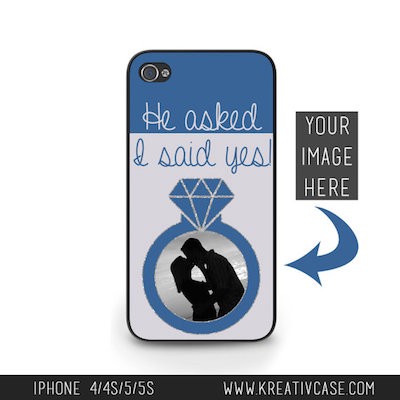

But the pull is strong. The more people have elaborate weddings, the more pressure for others to have similarly elaborate weddings — pressure applied by friends, mothers, mother-in-laws, and even groomsmen as they become accustomed to a certain lavish matrimonial standard. We could think of it as simple peer pressure, but I think something a bit more complicated — and insidious — is going on. Take the engagement iPhone case, dozens of which are available, in highly personalized form, on Etsy:

On the most basic level, these cases are part of a phenomenon that one friend, deep in the trenches of wedding-planning, referred to as “buy all the things.” At few other times are we given a sizable, ever-expanding budget and told to spend it on whatever makes a day “perfect,” even if that means spending outside our means. I imagine it somewhat like the shopping sprees on Nickelodeon’s Super Toy Run, when you just manically run down the aisles shoving things in your basket. Maybe that’s how some brides feel on Etsy today, especially the ones who haven’t been meticulously planning their weddings for years: just put all the things in your basket and press purchase.

But the “buy all the things” mentality doesn’t completely explain these covers. If our phones have become our primary mode of engagement with the world, then our phone cases (or lack thereof) communicate something about ourselves in the same vein as our choice of eyeglasses. An indestructible Otter case = a dad or very sensible; bedazzled = teen girl or irony; covers that suggest a book, cassette tape, or other analog technology = rhetorical hipster resistance.

So what does your engagement phone cover say about you? That you’re taken, sure. In that way, it functions like an amplified engagement ring: I am coupled; do not hit on me. But the case is less of a man repellant than a broadcast system to other women: I won. You may not be the first to get married, but if the overarching task of a 20- or 30-something American female is to have a guy “put a ring on it,” then you won. The phone cover functions as an odd form of surveillance, propping up the validity of the “game” and the inclination to visually celebrate its victory.

But this somewhat aggressive pronouncement is often packaged in passivity. The “He asked; I said yes” suggests just how little agency the (presumably female) partner has in engagement scenario. She may get to plan the wedding, but she has little control over whether or not it’ll happen in the first place. She has decorating power, in other words, but no actual power. In this way, the cover functions as a precise condensation of postfeminism, in which the politics of feminism are traded for the bounty of consumerism — when the freedom to choose becomes the freedom to consume or, in this case, choose the color and design of wedding dress, floral arrangements, and engagement phone cover.

As for the “Soon to Be Mrs. [Insert Husband’s Last Name Here] covers, they’re just straight-up regressive, less postfeminist than pre-feminist. I’ve seen rhetoric like this before, but only in one of two places: on tank tops made especially for the night of the Bachelorette party and designed to be barfed on; and in classic Hollywood melodramas. Regardless of context, it figures marriage as a traditional sublimation of the woman under the man’s identity.

Granted, millions of women still take their husband’s names, but there’s something different about the phone cover announcement — something territorial, even defensive. In proclaiming yourself the future “Mrs. Courtney Cole,” you not only broadcast your status, but his. Much like Peggy Olson’s “Mark Your Man” campaign for Bel Jolie lipstick in Mad Men, these covers provide a means for socially and politically impotent women to use what’s available to them — namely, commodities — as a means to control men.

It’s easy to think that these covers are just an exponent of Etsy and Pinterest culture, where the postfeminist rhetoric of “having it all” blends with the traditional feminized pursuits of crafting, collecting, and “nesting.” And that’s certainly where these covers — and dozens of other products like them — thrive. Yet that’s an easy way of compartmentalizing a trend that is actually far more widespread, isolating the problem to a group of people “not like us” or, at the very least, “not like me.”

But you can find the same ideology, albeit slightly modified, all over the bourgeois and hipster internet:

These covers are from Society6, a site once described to me as “Urban Outfitters + Threadless + Phones.” Both Urban Outfitters and Threadless are perfect examples of commodified indie taste: why go to the thrift store for a weird message tee when you can buy it for $22 online? Most of the phone covers hover between the cool (Bill Murray’s face), the ironic (Taxi Lllama), and the abstract, but dig a little deeper, and you’ll not only find the the covers above, but their little sister as well: the “I Love My Boyfriend” cover.

It’s nestled between covers that broadcast “I’d Rather Masterbate” and “Netflix is My Boyfriend,” but the message, a sort of postfeminist starter kit, remains. Over at Nordstrom, you can buy a Kate Spade cover, part of the designer’s “publishing series” that, in theory, evokes literary sophistication by reproducing the cover of a famous novel. But in practice, it replicates the same rhetoric as the Etsy covers.

It’s difficult to know exactly what’s going on with this particular cover — who’s the ideal consumer? Does Kate Spade and, by extension, Nordstrom, think this is a cute play on romance novels? Does a man buy this cover for his beloved? Does a college student buy it aspirationally? The answers to those questions matter less than the covers’ very existence: if Kate Spade sells it at Nordstrom, people are buying it and brandishing it in public.

When it comes to the wedding industrial complex, it’s tempting to blame the brides who are its most visible exponents, breaking down on Say Yes to the Dress or posing ridiculously in yet another set of engagement photos on your Facebook feed. But this is what happens when modern capitalism meets patriarchy, and the last 200 years have been a slow march to this logical conclusion.

In the end, the engagement phone cover says less about our specific cultural moment and more about the unyielding resilience of patriarchy and the industries that support it. The solution isn’t to ridicule these cases and the women who buy them, but to continue the much more difficult, frustrating, yet absolutely necessary work of challenging — and illuminating — the often invisible systems that produce them. Alternately, get on Etsy and start designing the feminist phone case of your choice: you may have to put “I asked, He Said Yes: Soon to Be Life Partners in the Eyes of the State” in smaller print to get it to fit on the case, but just think how loudly it would speak.

Previously: Suri’s Burn Book and the Celebrity Offspring Economy

Anne Helen Petersen mostly writes about celebrity, feminism, and media, and will soon do all of those things for Buzzfeed. Follow her at @annehelen.