On the Affirmative Action Ban in Michigan

From the New York Times:

In a fractured decision that revealed deep divisions over what role the judiciary should play in protecting racial and ethnic minorities, the Supreme Court on Tuesday upheld a Michigan constitutional amendment that bans affirmative action in admissions to the state’s public universities. The 6-to-2 ruling effectively endorsed similar measures in seven other states. It may also encourage more states to enact measures banning the use of race in admissions or to consider race-neutral alternatives to ensure diversity.

States that forbid affirmative action in higher education, like Florida and California, as well as Michigan, have seen a significant drop in the enrollment of black and Hispanic students in their most selective colleges and universities.

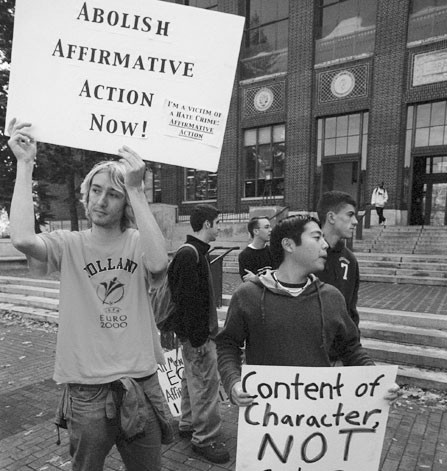

For the past year I’ve been teaching at University of Michigan and watching students from all backgrounds try to force the school to deal with what it means that black undergraduates are now at 5% of the student body (a number noticeably off from state demographics: 14% of Michiganders are black). All year people have been agitating ferociously for an educational environment where administrators would not immediately sound disingenuous when saying the word “diversity,” but the peculiar proto-justice that Jennifer Gratz hath brought upon us shall hold. Gratz, the (white) original plaintiff in the 1996 case, recently challenged a black Detroit high school senior to a public debate over affirmative action and stated, “Should we have a limit on how many Asians we admit? The government should be out of the race issue.” She has called the Supreme Court decision a “great victory.”

Michigan, whose online “ethnicity reports” are laughably half-assed and whose legacy-preference admissions policies are well intact, has otherwise acknowledged the ongoing protest by pledging to refurbish the multicultural center and consider digitizing some old civil rights documents, which one Huffington Post writer gives as evidence that “the University of Michigan Black Student Union’s work for increased tolerance and diversity has paid off.” Their work for tolerance! What a word, what a word.

I don’t know. I’m from a neighborhood in Texas that is 93% white and went K-12 in the same demographic and even though I tutored in my neighborhood for long enough to become quite accustomed to hearing white people tell me about how they’re the worst-off when it comes to college admissions, the racial atmosphere on campus here still reads insanely weird to me; this is still by far the most homogenous environment I’ve ever experienced in my life. I talked to my (nearly all white) students about race pretty often and oh boy did their voices grow awkward if they ever tried to discuss discrimination, which is what they called all that regrettable stuff America had done once upon a time long ago to people who were African-American, which is a word a lot of them said formally, in that “what had happened was” style; many of them couldn’t say the word “black” without hesitation; in my one class with a black girl half the kids stared at her every time we talked about rap, poverty or crime.

Last night I was rereading Kartina Richardson’s amazing essay “How Can White Americans Be Free?”, which includes an incredible theoretical reading of none other than Spring Breakers:

The absence of time makes for a very spiritual place indeed, and Faith, whose spirituality is the clearest as a Christian, says she wants to pause time and calls it “the most spiritual place,” a place where everyone is the same. Faith proclaims her love of this uniformity again and again. Everyone is “like us,” she says (young, beautiful and white). They are all the same. And that means no one exists to remind them of their external identity.

To be isolated from history in a hall of mirrors is heaven to a young person, and the bliss of this collective, amnesiac atemporality on some campuses extends way beyond spring break. Richardson’s piece is so remarkable because this all leads her to a point of clear-sighted compassion: “I realize that the obviousness of racism against brown people is a grace for us,” she writes, “a grace because it is so clear and tangible. While that which oppresses whites is harder to see and is not discussed.”

In order for white suffering to have a voice, white people must realize the largest and most invisible way in which they benefit from their white privilege, and it’s the same thing that’s causing their frustration being The Default. If Person A is actively supporting and benefiting from a system that oppresses Person B, it is very hard for Person B to hear Person A say, “But I’m hurt too!” However, if Person A is actively working to dismantle the system they benefit from but which oppresses Person B, then Person B is finally seen — and Person A’s pain can be embraced. In order to see a person you must see the truth of their pain. If you deny their pain, you refuse to see them. This is what makes black people invisible. And black invisibility is what makes white pain invisible to black people.

And so we live our lives never seeing each other.

And so it goes in these states, and likely more to come.