What’s Essential: A Conversation with Nona Willis Aronowitz About Her Late Mother’s Work

by Jen Doll

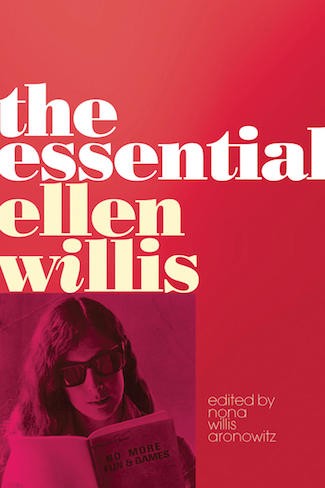

Ellen Willis was born in 1941 in the Bronx, grew up in a middle-class family, and, for a while, did what was expected of her: she married “a nice Jewish boy from Columbia while majoring in English at Barnard,” writes her daughter, journalist Nona Willis Aronowitz, in her introduction to her late mother’s recently published compendium of essays, The Essential Ellen Willis. At 24, though, Willis divorced her husband, got an apartment in the East Village, and started writing about rock, politics, culture, feminism, and sex. She went on to become the first rock critic for The New Yorker, an editor and columnist at the Village Voice, and a prolific, savvy essayist on a wide array of cultural topics.

The Essential Ellen Willis is some 500 pages of excellent, important writing from the author, and it’s utterly readable, too. The book includes Willis’ writing spanning forty years, along with introductory essays by Ann Friedman, Irin Carmon, Spencer Ackerman, Cord Jefferson, Sara Marcus, and Stanley Aronowitz, who offer a contemporary perspective on Willis’ work, and highlight just how relevant it remains.

I talked to Nona about what she learned about her mom, and herself, in the process of editing and publishing the book.

This is a collection of your mom’s writing, but you’re a writer, too. How does publishing this feel different than, say, publishing your own book, which you did in 2009 with Girldrive?

With your own book, it’s far more nerve-wracking. In this case, the pressure is off, and it’s been a really pleasurable experience. It does feel like a big deal, though. I put together Out of the Vinyl Deeps [her mom’s music writing], which came out in 2011. I had no idea how successful how it would be. I was doing it for posterity, and this whole new generation discovered her on Tumblr. Now I know what to expect more.

A lot of your mom’s work has a kind of frank accessibility I tend to associate with internet writing of today. How did you decide what to include?

I used that metric: Would this translate well on the internet? Some things wouldn’t, and I had to include them anyway, like her more radical essays on feminism. But when I was making brutal cuts, which I had to do, I thought about what would translate best to the way we consume writing today. People are pretty transparent about their thought processes in certain corners of the internet, and she was a master of letting her thought process hang out for all to see. She would employ the first person, argue with herself, just hang out with herself.

What was gathering the material like?

I went to her archives at the Radcliffe Institute, and looked through everything. She kept all the clips that really mattered to her. I was going through things, from writing from her internship at Mademoiselle to things she’d written a few months before she died. The original table of contents was 150,000 words over. I had to read all of her unfinished book about psychoanalysis. I was dreading that, but it forced me to engage with the ideas, and that was a really interesting process. I wanted to spread what we included out over the decades pretty evenly.

Do you have favorite pieces in the collection?

I think one of my favorites is “Coming Down Again,” where she grapples with what the counter-culture has become in an age of extreme backlash — the Reagan era, “just say no” and all that. It takes so many seemingly disparate topics and puts them together in this one thread of what pleasure means versus excess. It’s so relevant. I think my favorite of all time is “Next Year in Jerusalem.” It’s a piece about her brother converting to Orthodox Judaism, and her going to Israel to find out why. The reason that’s my favorite is because instead of brushing off what was going on with her brother as crazy or dogmatic, she really struggled and engaged. She bumps right up against her values, and really questions why feminism and freedom and doubt are important to her, even if she doesn’t seem outwardly as happy as these people she’s comparing herself to. That’s exactly what these Phyllis Schlafly-type people are always saying, “You’re not happy, you should join us.” My mom thinks, “Why do I hold these values so dear?” and she ends up affirming her choices.

Some of these pieces were written 40 years ago. What makes them still relevant today?

“Up from Radicalism” is still really relevant for anyone who comes from a conservative background and suddenly discovers leftist ideas. This narrative is still so applicable. On one hand, it’s depressing we’re dealing with the same issues, on the other hand, they’re still relevant because she talks in such general terms, she gets to the root of these issues. I think if more people had done that maybe we wouldn’t keep spinning on the hamster wheel; maybe we’d be talking about these deep-seated issues with regard to patriarchy, fear, and misogyny, not just skimming the surface with a woman’s right to choose. There are very few people who go that far. It still feels new and it might push the conversation forward. And we’re still talking about motherhood, having it all… she never uses that phrase, but it’s in “The Family: Love It or Leave It,” and “Is Motherhood Moonlighting?” She actually proposes solutions. She said women should be compensated for being stay-at-home moms, part-time workers should be paid as full-time worker because of what women are contributing to society. She’s not just saying what people have said.

How do you compare what freelance writing was like for your mom, at that time, with your own career and today’s publishing world?

It’s a lot more extreme for us. She’d do one piece to sustain her for a few weeks or months, and just not worry. When she was at the New Yorker she got a monthly stipend no matter what she wrote. She was living in a hippie commune in Colorado, writing a piece of rock criticism every few months and sustaining her hippie commune. That kind of thing doesn’t exist anymore.

What did you learn about your mom in the process of writing the book?

There are really personal essays in there. I learned she had an abortion and that she was raped. She’d never spoken to me about either of those things. She alludes to them. She didn’t tell these stories in detail, she offhandedly said they happened. I learned she struggled with depression. I don’t know if she’d call it clinical, but I got a sense of how depressed and repressed she was growing up in the ’50s. “Up from Radicalism” is a timeline of her becoming a radical feminist. It’s so vivid. I always wondered about her first husband. She really explains it in this piece. She had this cognitive dissonance of wanting to fit in on one hand and escape on the other hand; she knew in her wedding dress it was the wrong thing to do and she still did it. I didn’t know my mother when she felt so conflicted, by the time I knew her she was very clear what she wanted out of her life.

There are a few boyfriends of hers in these pieces, too. Her boyfriend that she stayed in Colorado Springs for, he’s a really cool, post-hippie dude living in Boston now. I visited him. And of course, Bob Christgau. Those two people have very different personalities, but they both still have such obvious respect to her and her intellect, and they both admit she was a very important person in their lives. I feel a kinship with them. It’s cool to know people who knew her during her countercultural transformation from someone who was married and had no idea what she wanted to a fully formed human.

How do you feel like your parents influenced your own feminist and cultural views?

I think I said this when Girldrive came out. My mom was not really the type to sit me down and lecture me about what feminism meant and force me to adhere to a certain value system, and that wasn’t my dad’s style, either. They were leftie and accepting. My parents were remarkably hands-off without being parents who let me do whatever I wanted. They let me discover myself.

My mom was also really different than her writer persona. She was shy and not that outgoing. I feel like I was one of the only people who really knew her, who got the privilege of knowing the personal side of her. It was really clear that she had resolved to be a feminist mom. I think of the time I realized I needed a morning-after pill. I was a girl of 16, and some moms would have freaked out, but she called her gynecologist, they got me the pill, and it was fine. I was grateful for that, she didn’t make a big deal of it.

Also, having radical parents who read all the time and talked about ideas rather than logistics was a big thing. I have vivid memories of them at the breakfast table talking in a really leisurely way for hours about real stuff, not like, “Did you pick up the dry cleaning?” Maybe that made for a disorganized household, but it was a real model for how I want my relationships to be. I don’t want them to devolve into talking about things that don’t matter.

Portions of the book are introduced by contemporary writers: Sara Marcus, Cord Jefferson, Irin Carmon, Ann Friedman, Spencer Ackerman. How did you choose them?

I kept in mind who I’d known was a fan of hers. Sara, obviously, I felt like she was the one who understood why we needed this anthology [Marcus wrote a piece following the publication of Out of the Vinyl Deeps calling for an Essential Ellen Willis anthology]. Irin, I thought of her because she discovered “Abortion: Is a Woman a Person?” and tweeted it and said it was so super-relevant. She was perfect for translating some of Mom’s ideas into the current landscape of reproductive rights. Ann, I decided I wanted her to do it after I read “Coming Down Again.” I was like, O.K., a few white ladies, but who would be people who can push her ideas further into a space that it’s not necessarily comfortable in? I wanted to have dudes who wrote about things other than sex, feminism, music. Cord, he’s a real iconoclast, a great writer, and someone who exposes his thought process in his writing. And Spencer, you wouldn’t think he dabbles in the same topics at all, but we went to the same radical socialist camp, and I knew he knew where my mother was coming from. I had never really read her recent work, the 2000 stuff, until I was putting this together. I realized she was preoccupied by war and terrorism and what our national identity meant. He wrote my favorite intro. I hate to pick favorites, but his is mine, because he argued with her!

What do you think in this book will most resonate with a Hairpin reader?

Definitely “Coming Down Again,” not to beat a dead horse. Also “Lust Horizons,” she basically coins the term pro-sex feminism, and I think Hairpin readers understand that feminism needs to include pleasure and sex. She wrote that in 1981; she and her radical feminist friends had been talking about sexual pleasure as a central idea from as far back as 1968. She was horrified when she saw the conversation being dominated by anti-porn activists. I also think Hairpin readers would really like her music criticism, the Janis Joplin piece, her feminist ideas mixed with pop culture.

Your mom passed away in 2006. What does it mean to be able to do a book like this now?

I’ve done so many projects that are centrally or tangentially related to her. Girldrive was partly inspired by her death. Some people cope with death by trying to not talk about it. That is not how I’ve dealt with it, obviously. I don’t know if at this point our work is in conversation with each other. I was 22 when she died, and I have written stuff I wish she could read and comment on. It’s really sad to think she’s never going to read it.

What do you think your mom would be surprised about in recent news?

I think what would surprise and delight her is what’s going on with teen girls online, the Tumblr culture and Vine culture with teen girls expressing themselves. When she died, it was the Bush era, and conversations around teen sex were much more repressed. I think teens have stepped up and are speaking for themselves, and she would have loved that. I wish my mom knew about Tavi.

How do you think she’d react to today’s internet?

She wasn’t one of those cranky people who thought the internet was going to destroy journalism. She had a job at NYU, she probably could have afforded to write for places like n+1 or The Hairpin, places where you can keep your editorial integrity. I think she would have done that.

Photos courtesy Nona Willis Aronowitz. The Essential Ellen Willis is out now.

Jen Doll is a regular contributor to The Hairpin and author of Save the Date.