The Big Book of Female Killers, Chapter 2: The Marquise de Brinvilliers

by Tori Telfer

This is the second installment of “Lady Killers,” a new series. Read Chapter 1 here.

Poison fits easily into the home. It’s subtle, secretive, tidy. It doesn’t leave blood on the floor or holes in the wall. Dropping a bit of colorless liquid into food or drink is a total breeze. And who, historically, stirs the batter, serves the wine, and is exceptionally invested in keeping the floor clean? Women, of course.

Paris in the second half of the 17th century oozed with poison and the fear of poison and, by extension, the fear of women: divineresses who dabbled in arsenic, spells, and abortions, and the rich young wives who frequented them, desperate to become rich young widows. The Sun King’s court was steeped in intrigue and hatred, and the poisoning paranoia got so bad that anyone with a stomachache panicked, sure that someone, somewhere was trying to do them in. Major advancements in pharmacology — coupled with a very real fear of black magic — created the perfect atmosphere for a poisoning witch-hunt, known today as the Affair of the Poisons.

“How can… those who are so sensitive to the misfortunes of others… commit such a great crime?” wrote a bemused commentator at the time, shocked at the amount of female poisoners who’d been convicted. “If some have been found so unhappy as to have fallen into such excesses, they are monsters. One must not suppose them like others, and they are sooner compared to the most evil men.” Sure, it was soothing in a weird way to imagine that these poisoners were more like men than girls, but it simply wasn’t true. These were French noblewomen: they got their hair done, they went dancing, they conspired against the King’s mistresses. And the whole fatal thing was kicked off by a reckless little Marquise named Marie-Madeleine Marguerite.

Marie-Madeleine Marguerite d’Aubray was born in 1630 to a wealthy French family. Her father was the Civil Lieutenant of Paris, a plum job that was both highly influential and very well paid. She had two younger brothers and a little sister who was probably not as cool as she was, given that the sister ended up in a convent and Marie — well, Marie was just one of those bold, lovely, spirited girls, you know? She had big blue eyes, chestnut hair, and a figure that historians consistently refer to as small but “exceedingly well formed.” She was also smart. “The handwriting of Mmslle. Marie-Madeleine is excellent,” an instructors wrote to her parents. “Her letters are formed boldly, they are firm and clear, they might indeed be written by an adult and strong-charactered man.”

Handwriting wasn’t the only precocious thing about Marie. At one point, she claimed to have lost her virginity at the age of seven to her five-year-old brother — a statement she later denied. (It’s possible, though unproven, that her incest claims were actually code for sexual abuse.) As a young woman, she entered what historian Hugh Stokes calls an “extremely dangerous society,” filled with bored nobles, lots of gambling, malicious gossip, and built around “the most libertine court in Europe” (François Ravaission, Archives de la Bastille).

At 21, she married the wealthy Antoine Gobelin, the Marquise de Brinvilliers, whose fortune came from the glamorous field of dye manufacturing. Marie was now the Marquise de Brinvilliers, or “la Brinvilliers,” if you were writing a gossipy letter about her. Antoine’s income plus Marie’s dowry meant they were now a handsome, wealthy couple with considerable social cachet.

Were they in love? Was anybody in love with their spouse back then? Toward the end of her life, Marie wrote of a deep affection for Antoine, but soon enough after their marriage, both of them were openly taking lovers. This was scandalous, but not at all unusual; in fact, a young, attractive, wealthy married woman was practically expected to have a paramour or two. Taking a lover didn’t get you ostracized in 17th century France; it got you talked about.

Unfortunately, Marie chose one of the bad guys. Her lover was a devilishly handsome army officer named Godin de Sainte-Croix, a ladies’ man with a serious dark side, and the two were soon the deliciously scandalized talk of the town. Marie’s husband was busily carrying on affairs of his own and didn’t seem to care much, but her wealthy, influential father and brothers were absolutely humiliated by her dalliance.

Back then, if you were an important French person and someone was bringing shame on your family, you simply requested a little form for your nemesis’ arrest, signed by the King and known as a lettre de cachet. Ultra-convenient. So one afternoon, as the two lovebirds rolled around Paris in their expensive carriage, they were intercepted by guards flashing Monsieur d’Aubray’s lettre de cachet, and Sainte-Croix was promptly dragged off to the Bastille.

You can imagine the rage Marie felt at having her lover wrenched away from her by her father in public. She later wrote, chillingly, “One should never annoy anybody; if Sainte-Croix had not been put in the Bastille perhaps nothing would have happened.”

As Sainte-Croix whiled away two months in prison, he met a mysterious Italian named Edigio Exili, who was an expert in the fine art of poison. Serious poisoning hysteria hadn’t hit the Sun King’s court yet, and poisoning was still thought of as the realm of the sneakier Italians. (A French pamphlet from the time claimed that in Italy, poison was “the surest and most common aid to relieving hatred and vengeance,” as though it were simply describing some sort of gastrointestinal pill.) Marie claimed that Exili taught Sainte-Croix all about his wicked ways, but historians disagree — the Swiss chemist Christophe Glaser, apothecary to the King and celebrated scientist, was probably the one who furnished Marie and Sainte-Croix with their knowledge of poisons. In fact, when corresponding with each other, the lovers often referred to “Glaser’s recipe.” Either way, Sainte-Croix was introduced to poisoning, and left the Bastille with just the knowledge his furious lover needed to get revenge on her father.

Marie wasn’t just irritated at the temporary loss of her lover. She also needed money. Her husband was terrible with his finances, and Sainte-Croix was an extravagant lover, blowing through her income as though it were his own. In those days, it was common for rich women to fund their lovers’ extravagances; apparently Sainte-Croix purchased, among other things, a really fancy carriage.

As soon as Sainte-Croix was released, he rented out a laboratory and began whipping up illegal concoctions, with his mind on inheritance money (and inheritance money on his mind). Marie was completely into the idea, too. But they had to test out the poison first. So Marie put on her most sympathetic face and went to the Hôtel Dieu, the famous public hospital next to Notre Dame. There, she wandered among the sick, distributing poisoned jams and sweets to her favorites, and weeping inconsolably when they inevitably died. “Who would have dreamt that a woman brought up in a respectable family… would have made an amusement of going to the hospitals to poison the patients, for the purpose of observing the different effects of the poison she gave them?” wrote Nicolas de la Reynie, the chief of police at the time. Marie also experimented on at least one of her serving girls with a one-two punch of poisoned gooseberry jam and poisoned ham, which gave the poor servant a terrible burning sensation in her stomach and three years of poor health.

Confident that their mysterious poisons — which were really just arsenic and possibly some toad venom — were undetectable and highly effective, Marie and Sainte-Croix moved in on Dear Old Dad.

Over the next eight months, Marie patiently fed her father poisoned food and drink. His agonizingly slow death didn’t move her; she dosed him with poison 28 to 30 times in all. When her brother Antoine came to check in on their ailing father, he wrote to his boss in shock, “I have found him in the condition that was told me, almost beyond any hope of recovering his health… in such extreme peril.”

After months of vomiting, extreme stomach pains, and a burning sensation throughout his insides, Monsieur d’Aubray died on Sept. 10, 1666. The “cause of death,” according to his doctors? Gout.

The inheritance money was divided up between the four siblings, and Marie and Sainte-Croix quickly burned through their share of it. Soon enough, they were back where they started — desperate for money, chased by creditors, and resentful of anyone who’d ever opposed their love.

Marie’s brothers lived together, conveniently enough, but the older one, Antoine, was married to a woman who hated Marie — so Marie had no way of accessing their kitchen in order to poison the wine before fake-nursing them back to “health.” So in 1670, she arranged for one of Sainte-Croix’s servants to work at Antoine’s household. The servant, known as La Chausée, was the perfect guy for the job: he had a criminal record, a hardened conscience and, like Marie, a creepily patient temperament when it came to watching people die. La Chaussée went to work, and soon spiked an elaborate pigeon pie that both brothers ate with gusto. Soon enough, the men were experiencing burning sensations in their stomachs.

The death of Marie’s brothers was another excruciatingly drawn-out process. We’re talking months of suffering: vomiting, inability to eat, cramps, visual deterioration, bloody stools, swelling, weight loss, and that constant fire gnawing away at their stomachs. The older brother took 72 days to die; the younger brother took five months. It’s hard to imagine that any sister could watch her siblings die so agonizingly, for so long, but Marie was nothing if not cool in the face of death.

Autopsies for both brothers revealed the same wrecked insides: the stomach and liver were blackened and gangrenous, and the intestines were literally falling apart. Either the doctors weren’t suspicious — siblings always die of the exact same thing, right? — or didn’t consider it prudent to raise suspicion, because the d’Aubray brothers’ death certificates reported that they passed away “due to natural cause and effect of malignant humor.”

Now that all her closest male relatives were dead, Marie began plotting the murder of her sister (a devout single gal with a large fortune) and her sister-in-law (that annoying woman who’d inherited Antoine’s fortune, which Marie still wanted to get her hands on). She also attempted to poison her husband, but Sainte-Croix kept giving him antidotes in a horrifying back-and-forth that felt almost like a comedy gag. Madame de Sévigné, one of the greatest gossips of the time, wrote to a friend, “[Marie] wished to marry Sainte-Croix, and with that intention often gave her husband poison. Sainte-Croix, not anxious to have so evil a woman as his wife, gave counter-poisons to the poor husband, with the result that, shuttlecocked about like this five or six times, now poisoned, now unpoisoned, he still remained alive.” Needless to say, Sainte-Croix and Marie were no longer in their honeymoon period; a furious Marie even wrote him a letter threatening to poison herself with his formula, which she’d bought from him at a very high price.

As a matter of fact, Marie had taken another lover just after her brothers died. This man would be just as destructive to her as Sainte-Croix was, but in the opposite way; while Sainte-Croix encouraged her crimes, this lover would turn against her because of them. But for now, Marie knew nothing of her future. All she knew was that this new man was kind, and young, and good.

+++The man, Jean-Baptise Briancourt, had been hired as a tutor for Marie’s children in the fall of 1670, and became Marie’s lover shortly after. He was completely infatuated by the Marquise, but also terrified of her; she talked incessantly of poison and eventually confided in him about her crimes. He could see how cruel she was to her daughter, and suspected that Marie was trying to poison the girl. (She did, once, and then immediately gave her daughter the antidote — lots of milk.) Eventually, Briancourt suspected that the Marquise was plotting to kill him, too, and his fears were confirmed when he saw Marie — wait for it — hiding Sainte-Croix in her closet. The plan was that Sainte-Croix would jump out and murder Briancourt when he and Marie were making love later that night. Horrified, Briancourt called Marie an evil women; she, in turn, went into some sort of spastic rage and tried to strike at him. Despite all this, Briancourt was crazy about Marie, hoping beyond hope that she’d redeem herself and ride off with him into the sunset.

The Marquise had no interest in sunsets — she just wanted to get started on her next victim. But her murdering days came to a sudden end with the death of Sainte-Croix.

As the legend goes, Sainte-Croix was whipping up poisons in his secret laboratory on July 30, 1672, wearing a glass mask to avoid breathing the dangerous fumes. As he bent over the fire to stir some devilish pot, his mask shattered, and Sainte-Croix was immediately killed by the very poison he was creating. Irony and justice! Really, though, Sainte-Croix simply died after a long illness, with none of the authorities suspecting that he was a criminal.

He was, however, disastrously in debt, and during posthumous attempts to put his affairs in order, clues began popping up everywhere. The first was a mysterious scroll found in his laboratory, titled “My Confession.” Unfortunately for curious minds everywhere, the police decided that the document was sacred, and — since Sainte-Croix wasn’t accused of anything at the time — they tossed it into the fire. We can only guess at what Sainte-Croix confessed, but we can assume that his crimes lay heavily on his conscience toward the end of his life.

Another interesting object was discovered in the laboratory: a little box full of mysterious vials and powders, which turned out to be things like antimony, prepared vitriol, corrosive sublimate powder, and opium. The box came with a note saying that the contents should be immediately given to the Marquise de Brinvilliers upon the event of his death, because “all that it contains belongs to her and concerns her alone.” There were heavily-sealed envelopes marked “burn in case of death,” and one packet titled “Sundry Curious Secrets.” Suddenly Sainte-Croix, may he rest in peace, wasn’t looking so innocent after all.

The whole thing only got more suspicious when Marie rushed over to the authorities late at night, demanding that the box of poiso — uh, “curious secrets” — be handed over to her. La Chausée didn’t help, either; he started spinning a crazy story about how Sainte-Croix owed him a lot of money and oh by the way so did his former master, the late Antoine d’Aubray, who was definitely not poisoned or anything — but as soon as he found out that the box of secrets had been discovered in Sainte-Croix’s laboratory, he bolted.

When Marie’s sister-in-law heard about the mysterious box, she went on a legal rampage, demanding vengeance for her husband’s murder. She lodged an accusation against La Chausée, who was dragged off to jail as Marie fled the country. While French authorities scoured the Continent for the Marquise, La Chausée went to trial.

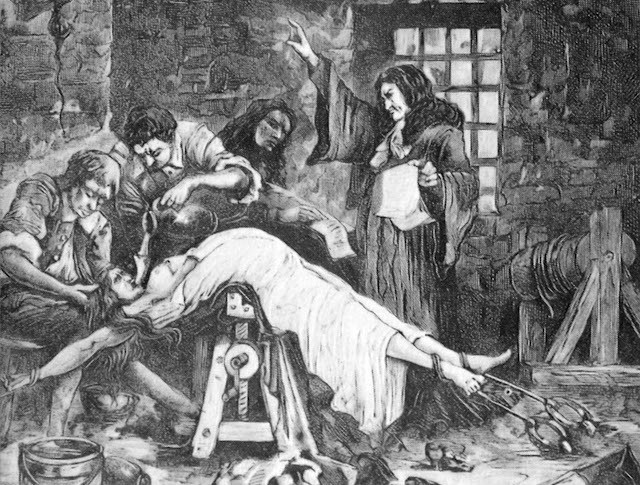

As a low-ranking member of society with a criminal record and an angry noblewoman on his case, La Chausée never stood a chance. He was found guilty before he had confessed a thing. On March 24, 1673, the judges sentenced him to be “broken alive and to expire upon the wheel, previous to which to be submitted to the Questions Ordinary and Extraordinary.”

The Ordinary and Extraordinary Questions were a form of water torture in which the victim’s nose was pinched shut, his body stretched backward over a trestle, and copious amounts of water forced down his throat via a funnel — twice as much water for the Extraordinary as for the Ordinary. After groaning through the Questions, La Chausée was also subjected to a horrific torture called the brodequins: his legs were fitted into iron boots, and wooden wedges were hammered into the boots, crushing his calves. La Chausée couldn’t take it. With his legs mangled and bleeding, he confessed that he had poisoned the d’Aubray brothers according to the wishes of Sainte-Croix and the Marquise de Brinvilliers. He was then tied onto a cartwheel, beaten repeatedly with iron bars, and left to die in agony. This style of execution was known as being “broken on the wheel,” and brings to mind a sort of cross — one where the victim dies facing the sky.

For exactly three years and one day after the death of La Chausée, Marie avoided capture. At that point, she was renting a convent room in Liège, which was then an independent city state. Upon her arrest on March 26, 1676, a sheaf of papers was discovered in her room. Like her lover, Marie had at one point been desperate to unburden her conscience:

I ACCUSE MYSELF, OH MY FATHER

I accuse myself of setting fire to a barn on my husband’s Norat estate and of having done this out of revenge.

I accuse myself of the loss of my virginity at the age of seven with my brother who, indubitably, could not at that time have been more than five years old.

I accuse myself of not honoring my father and of not respecting him as I should have done.

I accuse myself of committing adultery with a married man.

I accuse myself of having given much to this man who was my ruin.

I accuse myself of having two children by this man.

I accuse myself of having created scandals.

I accuse myself of poisoning my father.

I accuse myself of having given poison to my father twenty-eight or thirty times.

I accuse myself of selling poison to a woman who wished to poison her husband.

I accuse myself of causing my two brothers to be poisoned and that a lad was broken on the wheel for this.

I accuse myself of planning to have my sister, a Carmelite nun, poisoned.

I accuse myself of having taken poison myself.

I accuse myself of poisoning one of my children.

I accuse myself of having poison given to my husband.

Buried within the list of actual crimes, there’s a tragic vulnerability. Her reference to Sainte-Croix as “my ruin” is heartbreaking, as well as the fact that she regrets not just poisoning her father, but her failure to honor and respect him. Three years in exile, impoverished and alone, had apparently worn heavily on Marie.

But the Marquise wasn’t done fighting, and as she was dragged back to Paris for trial, she tried to kill herself multiple times by attempting to swallow pins and mouthfuls of crushed glass. If she’d been the talk of the down during her halcyon days with Sainte-Croix, she was even more famous now, and a salacious rumor began circulating that she had tried to impale herself on a sharp stick in a move that was half-suicidal, half-sexual. As a friend wrote to Madame de Sévigné, “She thrust a stick — guess where! Not in her eye, not in her mouth, not in her ear, not in her nose, and not Turkish fashion. Guess where!” La Brinvilliers had publicly carried on an affair for so many years that now, even rumors of her suicide attempts framed her in a hyper-sexual light. But Marie was no longer the wild child of libertine Paris. At 46, she was a marked woman, and she was exhausted.

Since she was a woman of high social standing, the court needed substantial evidence to prove her guilt. As incriminating as her “Confession” sounded, she denied the whole thing in court, claiming that she was out of her mind when she wrote it — feverish, confused, alone in a foreign country. Witnesses took the stand against her — one maidservant claimed that La Brinvilliers had gotten drunk after a dinner party and flaunted the box of poisons, laughing, “Here is vengeance on one’s enemies; this box is small, but is full of inheritances!” — but no testimony was quite enough to convict her, until the court brought in the one man who knew everything: Briancourt.

Marie listened to her former lover testify against her for a total of 13 hours. He told the court everything: how she and Sainte-Croix had killed her father and brothers, how she had asked him for help with the murder of her sister and sister-in-law, how she had plotted to murder him with Sainte-Croix in the closet. Marie listened with frightening calm, responding that Briancourt was a drunkard and a liar. When Briancourt actually began to weep on the witness’ stand, Marie called him a coward. The court was stunned by her eerie, unfeeling composure, but Briancourt’s testimony was exactly what they needed to convict her.

On the July 16, 1676, the judges declared her guilty.

Marie met with her confessor, a Jesuit priest named Edmé Pirot, earlier that morning. She hadn’t heard her sentence yet, but told Pirot she expected to be found guilty and sentenced to death by the end of the day. In Pirot’s account of their time together — an incredibly detailed, tender, empathetic book — he writes that she was “very little and thin,” and that she pitifully requested that dinner be a little heartier than usual, as she expected the following day to be “of great fatigue for me.” She gave Pirot a letter for her husband that overflowed with unexpected love, beginning, “When I am on the point of yielding up my soul to God, I wish to assure you of my affection for you, which I shall feel until the last moment of my life.”

On the 17th, she was informed of the court’s verdict. She’d be given the Ordinary and Extraordinary Questions, then beheaded.

Before the Questions began, Marie made a full confession to the court. Unfortunately, she didn’t tell them anything they didn’t already know — they were hoping for accomplices, dark secrets, important names. The poisoning paranoia had begun, and authorities were already panicking about the terrifying subtlety and (at the time) undetectability of poison. They feared that after Marie’s death, her poisons would somehow kill again. But if Marie knew more than she confessed, her lips were sealed, because she was in the final hours of her life now, and terrified of damning her eternal soul.

The official report of Marie’s torture, as reprinted in Celebrated Crimes by Alexandre Dumas, is difficult to read. The report begins with the Ordinary Question:

“On the small trestle, while she was being stretched, she said several times, “My God! you are killing me! And I only spoke the truth.”

The water was given: she turned and twisted, saying, “You are killing me!”

The water was again given.”

The trestle was raised, her body was stretched even farther, and the Extraordinary Question began, but still La Brinvilliers refused to confess any more than she already had, groaning that she would not tell a lie “that would destroy her soul.” After four and a half hours of torture, the men realized that if she had any more secrets, she was literally taking them with her to the grave.

A tiny, dirty tumbril arrived to carry her to the scaffold. She was barefoot, wearing a coarse white shift, with a noose slung symbolically around her neck. The execution of the scandalous La Brinvilliers was quite the happening event, and many Parisian nobles turned out to see her inglorious processional. When Marie recognized some of the noblewomen in the audience, she said to Pirot, “Oh, sir, is this not a strange, barbarous curiosity?” It was an incredibly humiliating ordeal for a woman of status, and Dumas claims that she broke down in shock and convulsed for fifteen minutes, mouth twisted and eyes blazing. A sketch of this awful moment, immortalized by Charles LeBrun, hangs in the Louvre today.

The procession eked toward Notre Dame, where Marie was forced to get out of the cart and perform a “public penance,” kneeling and saying aloud, amid the angry hissing of the crowd, “I confess that, wickedly and for revenge, I poisoned my father and my brothers, and attempted to poison my sister, to obtain possession of their goods, and I ask pardon of God, of the king, and of my country’s laws.” Later, Pirot wrote, “Some people say that she hesitated in saying her father’s name — but I noticed nothing of the sort.”

On the execution platform, as Pirot whispered prayers in her ear to calm her, Marie’s hair was brutally shaved and her shirt ripped open to expose her neck and shoulders. Her eyes were covered, and she obediently began to repeat the prayer after Pirot, when the executioner’s long sword flashed through the air. Marie fell silent.

Suddenly nauseated, Pirot assumed that the executioner had missed her head entirely, because though Marie was no longer speaking, she still knelt upright, with her head on her shoulders. Moments later, though, the head slid off her neck and her body fell forward. The executioner asked Pirot, “Was that not a good stroke?” and then immediately drank a mouthful of wine. As Marie had requested, Pirot began to recite a De Profundis, the Catholic prayer for the dead, over her bleeding body: Out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord.

La Brinvilliers was dead, and Paris was terrified, scandalized, thrilled. “The affair of Mme de Brinvilliers is frightful, and it has been a long time since one heard talk of a woman as evil as she,” ran a gossipy letter of the time. “The source of all her crimes was love.” But it wasn’t love, exactly. The source of all her crimes was money, and anger, and revenge, but since Marie had made no secret of her sexual appetite — flaunting her affair with Saint-Croix all around Paris — the narrative of the beautiful Marquise poisoning for love was a pleasing one, an easy one for society to latch onto. Despite its sick allure, her story also left Paris traumatized, and hyper-paranoid about the use of poison. If a lovely, wealthy woman could poison the men closest to her, then who wouldn’t poison? If a woman could kill not just for passion, but for something as prosaic as inheritance money, then who was safe?

“Well, it’s all over and done with, Brinvilliers is in the air,” wrote Madame de Sévigné to a friend. “Her poor little body was thrown after the execution into a very big fire and the ashes to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and through the communication of the subtle spirits we shall develop some poisoning urge which will astonish us all…. Never has such a crowd been seen, nor Paris so excited and attentive.”

In fact, some of Paris was so attentive that they watched the burning of Marie’s body till the very end. They wanted to see where her ashes were scattered. The people who stood closest to the scaffold reported that her face was illuminated by a halo just before the beheading. She was a saint, they said, and went searching through her ashes for bits of bone.

Previously: Chapter 1: “The Blood Countess”

Top art by Maya West.

Tori Telfer is a writer from Chicago prone to nightmares, writing about creepers, and snatching ideas for stories from happier dreams. Read more of her work at toridotgov.com.