Interview With My Dad, Whose Parenting Guru Was Marshall McLuhan

Happy early Father’s Day. What are you going to do to celebrate?

Mom and your brother have to tell me what they want to do. I’m not going to plan my own Father’s Day! I have kept my schedule open. Ideally you would be here and we would all be playing golf.

I’ve done my part to kill that dream for you. You going to play on Sunday?

Maybe Martin and I could, and Mom…

Never going to happen.

Maybe sometime in the future!

Do you think Father’s Day is stupid or do you like it?

I think it’s a good thing, just like Mother’s Day is a good thing; dads and moms do a lot of stuff for their families, and if we don’t appreciate it society will start to decay.

Is Father’s Day a thing in the Philippines, where you grew up?

We never celebrated it. But my dad was a ship captain, he was always away.

How many days out of the year?

Out of 365 days, he’d be gone 345 days. It was bad.

Did you feel like it was bad? Did you want him to be home?

Well, you just grow up not knowing anything about anything, and some people had their dads there all the time and they didn’t like it either. I thought, “This is my dad’s job,” and that was that. In retrospect it was good that he was gone. He was so autocratic — he was a ship captain from a young age, he was very used to having his way. If he’d stayed home, I’d probably have been a terrible father to you.

So I didn’t mind that he was gone, but I definitely didn’t like him when he was around. He thought his role in life was to come home and spank us for all the bad things we’d done in the last four months. I thought, “When I’m older, I’m not going to be this kind of a person.”

There’s a specific moment that’s sort of seared into the fabric of my brain, actually — I was six or something, my dad was getting an award and there was a real big do, some black-tie dinner, and we were at the presidential table. I was in black-tie, even: this big fat little kid. And I propped my elbows up on the table because I thought it was a really cool thing to do, and I knocked down a cup of water, and my dad took me to the back of the hotel and spanked me just to oblivion. My mom came and stopped him, literally to stop the bleeding, and we had to go take a picture right after, and I’m just crying and crying in it.

We had that picture framed in the house — a glossy 8×10 — and I just always thought about it, maybe more when I was a teenager: when I have a family, that’s not going to happen. That’s why we always had that rule in our house. We never punished you for accidents, no matter how bad they were.

What you’re describing is child abuse under contemporary definitions, isn’t it?

Absolutely. But everyone got spanked growing up.

Did everyone get spanked that aggressively?

Not really. But in general, it was okay in that culture. I had no conception that what my dad was doing was objectively bad. I just knew I didn’t want to do it. Kids are interesting because they don’t know any better. They frame the picture and create their own reality.

When did you start thinking about having kids in a more tangible sense?

When I met your mom. Hey, actually, you wanna know my secret to being a good dad? Marrying a good mom. I met your mom and really wanted to marry her. I was visiting her house and courting her — that’s an old-fashioned word, sorry — but I saw her look after her dogs, and she was really good with them. She had three: an old German Shepherd, a poodle, all cute ones. They obeyed her, and she was really kind to them, and I said, “Man, if this chick can do it with dogs, she can do it with human beings.” And then she taught me how to play the piano and she was really patient — and I said, this is it.

You guys were how old?

16. Really young.

When did you guys start talking about kids?

We didn’t want to have kids right away after we got married, which took us a long time — she was 26 and I was 27. We didn’t have the money at first. People were kind of concerned that we weren’t having kids; they were like, “Is something wrong?” and I said, “Excuse me, everything’s fine in that department.”

And listen — you and Martin were not randomly raised kids. We really had a plan.

You had your little method.

Yeah. You know Marshall McLuhan? The Medium Is The Message?

LOL. Dad.

I’m serious! I had this professor in college who was a student of McLuhan’s. So that’s how we approached parenting — the medium as the extension of ourselves, the message as all the unanticipated consequences that would come after.

So. You’d be sitting in your baby chair eating cereal in the morning, and your mom would sit directly across from you and just read the newspaper very slowly. And I’d come home and read in front of you. And then you were like, “That’s what people do — they read.”

So just modeling behaviors?

Yeah. We were very intensive with you until you were three years old, and up till about six we were really careful to manage the negative vibes in the house. We tried to never let you see anger. And then after six, we were very hands-off. We really didn’t parent you at all.

When you found out you were having a daughter, did you have any gender-specific thoughts about it?

We didn’t know you were a girl until you were born, actually. I was happy, because I wanted a girl. Mom was neutral. But I think girls should be born first.

Why?

Oh, just because my older sister was a girl, and you only know what you know. She was a really responsible older sister. My mom was working in America for awhile, so we were really a family of parentless kids, and she was the mother hen.

What about my brother? How was it different parenting a boy?

I think it was more like first time and second time, versus boy-girl. We were really careful with you — it took us an hour and a half to get you dressed, and we were terrified that you would slip when we were giving you baths. With Martin, not so much.

What was hardest for you as a parent? Were you ever like, “What am I doing?”

Just the sleepless nights. You never think truly, “What am I doing with this child in my arms,” you think, “This is fun and everything, but I’d like to go to sleep.”

How many kids would you have wanted to have, if all factors had been in line?

I think I’d have wanted four. Mom wanted like, four or five.

Mom stopped working when she had me — did you feel more professional and financial pressure, to support the family?

Of course, but also we decided that together, about her staying home. I was just working as hard as I could anyway. I think I’d have done that, regardless.

You were very involved with us. More than is typical. Were you aware of that?

Yeah, my friends would ask, “Why are you doing these things with your kids, why don’t you just, like… let them go?” But I thought you guys were interesting. I guess you were certainly more fun to me than a lot of their kids were to them. And also, traveling for work made me miss you guys a lot, so maybe when I was there I was more affectionate.

Yeah, you were really affectionate. I’ve always known that had some effect on me. I feel like I have the reverse of daddy issues — like, if anything, I push affection away.

Oh, you were always like that, starting at like, nine years old. You never had any need to be told that you were pretty or good. And you are pretty and good, but you didn’t need to be told that.

Did you ever worry about me in the period where I was starting to go out drinking and stuff? I appreciated that you guys never policed me.

Mom and I both agreed on doing that. As much as you might think that we headbutt, we’re really in agreement on stuff like this. The two of us grew up fast — among friends, Mom was the alpha female, I was smoking weed all the time really early, whatever. And I had some good friends who were bridled and encumbered and controlled by their parents, and they ended up the bad guys. I was bad in high school and then I became the Christian one.

I want to preface that by saying, you were actually very good. You knew what lines to draw. And if the cops caught you drinking like that one time, I’d be there, Mom would be there. Everyone has to go through something like that. The secret is just to establish really strong foundations at an early age and let your kids go.

Another strong memory I have is cheerleading camp at A&M when it was pouring rain, and everyone had to run across this huge parking lot to get to the line where parents were picking their kids up, and you just drove way up on the concrete steps so I wouldn’t have to get in the rain.

Haha. Yes. All the other dads were like, “Why are you doing this?”

Was it easy for you to be generous with your time and attention as a parent?

It’s hard to answer that, whether it was easy or not. Every decision is a fork in the road. Should I be upset? Should I not be? Should I do this? Should I not? I wanted you to have an unsullied experience. I didn’t have a beautiful childhood. So I decided to start from scratch. And because he was gone so much, my dad’s style was not ingrained in me. I wasn’t working with the coal, my hands didn’t get black.

So that’s the cheer camp thing. I was in the line far away in the rain with everyone waiting for their daughters, and thought — should I stay here, or should I just drive up on the sidewalk? I went to a Jesuit school that preached that your decisions should be for others and not for yourself. They hit that concept on our heads from Pre-K to high school. The better decision is always the decision you make to benefit another person.

What were your favorite ages when we were growing up?

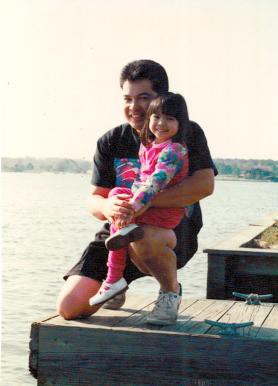

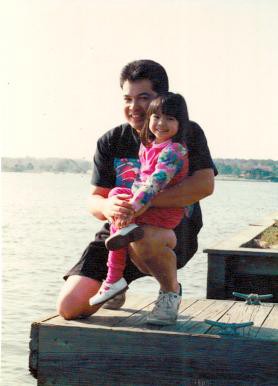

When Martin would come and ask me for stories — that was when he was three or four. My favorite age for you was around that time too, when you’d listen to a song and if it was a male singer, you’d think it was me. I remember the beautiful smile you had on your face when you came to greet me when I was coming home from work and you saw that I had the Beauty and the Beast VHS tape in the car.

And there’s the famous anecdote about when we went to Disneyworld and you were walking around the gift shop — around that same age, four — just touching things and saying, “This is really great, this is really great,” and I had to crouch down and tell you we didn’t have enough money for souvenirs. And you took my face in your hands as if you were my grandfather, and you said, “That’s okay, Dad,” and then you started crying really hard anyway.

Hahahaha. Of course I did. The medium was the tears and the message was “Still, I would really like some Belle memorabilia.” I feel like I haven’t changed at all since I was four — do you feel that way?

Yeah, you haven’t. I probably haven’t either. We’re all who we are.

Do you have any regrets from your time as a dad thus far?

You know, I guess I do. My job had me traveling a lot, and I wish I’d stayed home more. Then of course I wish things had been more stable financially for you when you were older, that we had a big house for you to come back to right now. I always wish we’d had money to give you in college.

Well, I think things worked out great. I think you’ve been an amazing, amazing dad. But related to the money thing: I was going to ask you, how much does being a dad, to you, mean being generous? How much does it have to do with literally being able to provide? I guess — what does being a dad mean to you in general, and how has it changed?

On a basic level, I think the evolutionary urges of a person are to say, “Let me see if I can pass on my DNA.” That’s really compelling for everyone, for animals, for people. And that’s a lot of the initial drive to have kids. You don’t want to have a baby for the hassle of it, you know? You’re like, “Let’s see what we can do here.” So that’s what it meant to me before.

Then you have a child. And that kid has a whole life to go. Her life is longer and thus more important than yours. I parented like you were more important than I was, and that comes not from my family or my own parents but from my education. And being generous with someone doesn’t always mean you have to provide financially. Some of our most generous moments with you and Martin were when we (Mom and I) had very little in the bank, and very little to give.

It’s interesting, too, because you and Mom both come from a culture that’s separate from the American model where you put the kids in a million activities and spend your life driving them around. Like, Mom was raised by nannies, right? And yet you guys spent so much time on us — and defined yourselves, I think, as parents. You call each other Mom and Dad. Did you ever regret giving up so much of yourselves?

No, because the results were instantaneous. Every moment of sacrifice immediately resulted in another immeasurably memorable moment. Mom and I would do it all over again. Yeah, man, absolutely no regrets.