La Malinche, La Llorona, La Virgen: My Mother’s Ghost Stories

by Teresa Finney

Mom tells the story with a smirk on her face and an eyebrow raised, as if she’s revealing something wicked. “It was late, sometime after midnight. I was on the phone with my boyfriend and all of a sudden I felt a cold draft. I thought I left a window open.” The words coming out of Mom’s mouth are suspended in the air, waiting for a reaction. I’m listening, but not really; I have heard her tell this story countless times.

“All I know is that I tried to turn around to see where the cold was coming from, but I couldn’t move. I was frozen! I was laying in bed on the phone and I’m paralyzed, I can’t move. That’s when I see her. She’s in the doorway of my room just staring at me, dressed in all white. I try to scream but I’m just paralyzed.”

The first time I hear her recount this night, we are at my grandmother’s house. It’s after dark and I am very young, maybe seven. The women have gathered in Grandma’s living room to tell ghost stories. “But they have to be true stories,” I say. “Something that has actually happened to you.” My mom goes on.

“I’m still trying to scream because I’m scared,” she says. “But just muffled air comes out. Finally, I’m able to scream. She disappears when your uncle runs in the room to check on me.”

I ask better questions as an adult. Was she pretty? I’m curious. I’ve never seen a ghost, let alone La Llorona, the infamous one. I want to know. (“That I don’t remember.”) How did you know it was her? (“I just knew.”) Have you ever considered that it wasn’t her? That maybe it was some other random ghost? (A simple “no” is all I get.) Were you stoned? (“Teresa, no!”)

Most Latino families have a version of this same ghost story; it is folklore that is deeply embedded into our culture, and when my mom talks about it you would feel as if she were recounting history. I never thought about not taking her word about any of it. This is the power of belief, the staying power of legend that is widely held but wholly unsubstantiated. Latinos are a spiritual people rooted in Catholicism; the religion is so inherent to our history and identity that my Catholic guilt lingers even a decade after disassociating from the church.

My family grew up in the church, but we were not religious people. For starters we were usually late for service; a good Catholic family would have been on time. We also never went to church on Christmas Eve because the adults (and later, as we grew up, the grandchildren) were too drunk from tamale-making to drive, let alone show our sinner faces in front of God.

But when I was 27 years old I walked into St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan, desperate to feel something familiar 3,000 miles from home. I sat down in a pew and cried as sunlight from the stained glass windows painted my face.

+++

There are three iconically potent female archetypes in Chicano culture: La Malinche, La Llorona (the woman my mother supposedly saw in her bedroom in the 1970s) and La Virgen de Guadalupe. Walk into any Hispanic household and your chances of seeing some representation (or even an entire shrine) of la Virgen de Guadalupe is very high. In Hispanic culture she is the ideal; the revered Catholic icon, the purest form of woman. She is the mother of God and the saint we pray to when our loved ones are on their deathbeds, or after we have just purchased a lottery ticket. In her form we are told that this is the impossible standard to which we should hold ourselves to. There is a silencing of female sexuality in our culture; we are often afraid of being even casually sexual, a fear I believe is perpetuated through the idealization of la Virgen de Guadalupe. Still, she offers comfort to many Hispanics, and it is this line between ancient belief and the experiences we have as women that Chicana feminists must learn to reconcile.

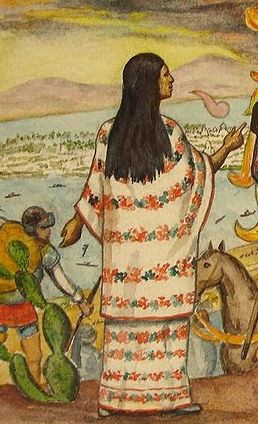

La Malinche, or Dona Marina, the slave and mistress of the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes, has become the Hispanic representative of female sexuality. She is iconic in our culture for playing a role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire and later, for giving birth to one of the first Mestizos (a person of European and indigenous American ancestry). Malinche is known for having seduced Cortes and because of her role in the war, people believed she was the embodiment of treachery. To this day in Mexico, the term malinchista refers to a disloyal person. Many Latinas are told from a young age to deny or repress the kind of blatant sexuality we saw in La Malinche. If we don’t, we run the risk of being called a whore, a woman asking for it. There is not one thing more disappointing than this to a Hispanic father.

La Llorona is something else entirely. First introduced to me as a child, I knew her story to be folklore, but many people believe she was a real woman who existed sometime in the 1500s. She was a woman betrayed. When her husband decided he was done with her, he left to be with another woman, and she drowned their two children in a nearby river out of anguish and revenge. The legend is that she roams rivers and lakes in Mexico, California, and the American southwest, searching for her children, wailing from the pit of her soul. She is doomed to live eternity in “the in-between” — not quite on Earth, not quite in the afterlife. Hispanic parents tell their children this story as a cautionary tale so they don’t wander far from home, but I’ve come to believe that one of the reasons La Llorona’s story has survived as long as it has is because it reinforces a sense that women are inherently sinful and must be controlled. It’s an ancient, undying belief.

These three figures represent the roles available to women in Mexican heritage: la madre, la virgen, y la puta; the mother, the virgin, the whore. Many Chicana feminists (such as Sandra Cisneros and Ana Castillo, just to name two) are invested in exposing and deconstructing this severely limiting ideological structure. The belief is that if we dismantle damaging ideologies which are revealed and perpetuated through stories about “Our Three Mothers,” as they are sometimes referred to, we examine the virgin/whore dichotomy and reconceive the role of women in Hispanic culture.

I, for one, wasn’t exactly raised with feminism as a specific ideology. My grandmother, aunts, and my mother were too busy working, raising families, and taking care of the men (like good Hispanic women do, right?) to consider things like reproductive rights or the consequences of sexual violence. My grandmother certainly did not have the luxury to sit back and think about her status in a male-dominated world and wonder, what did it all mean?. She raised six children, kept up their modest home, dealt with racist neighbors (my family was the only non-white family on their block at the time), and got back-handed by Grandpa if she raised her voice at the dinner table. A thing like feminism was reserved for gringas.

+++In her essay “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess”, Sandra Cisneros writes:

La Virgen de Guadalupe was an ideal so lofty and unrealistic it was laughable. Did boys have to aspire to be Jesus? I never saw any evidence of it. They were fornicating like rabbits while the Church ignored them and pointed us women toward our destiny — marriage and motherhood. The other alternative was putahood.

I keep a 2×4 laminated card with an image of Guadalupe (“The Queen of Mexico”) on my nightstand. She stands, hands posed in prayer, draped in blue cloth with gold stars (“to show that she is from heaven,” my grandmother says) and a red dress. The “luminous light” surrounding Guadalupe symbolizes that God has sanctified her. She is standing upon a crescent moon, and I only know this is a moon because of research — my entire life up until today, five weeks before my 30th birthday, I thought that moon was actually a set of horns.

My grandparents had a very large painting of la Virgen in the hallway of their home, and whenever I walked down that hallway, the same house where my mother saw the apparition as a teenager, I would see the horns and feel creeped out. Religion was a mysterious, almost scary thing to me as a kid; it rarely offered the kind of comfort my family and other members found in our church. And the moon supporting Guadalupe, I now know, represents her “perpetual virginity.” This idea is just one reason I rejected so many stories in the Bible; the immaculate conception was a whole lot of nah to me.

But I knew the impact she had on my grandparents, I knew how wholly and devotedly they respected her, and because of that I could not, I can’t dismiss her entirely.

I am the eldest granddaughter, and that comes with certain responsibilities and duties — to get married, have children, set the example for younger family members. I have mostly dismissed What Is Expected of Me because it simply does not fit me or my lifestyle. I am the wild one of the bunch, the unmarried, childless, almost-30-year-old writer. Up until very, very recently, “Chicana feminist” was a mirror I did not see my reflection in. As a teenager, a classmate used the word “spic” in my presence while talking about another Mexican kid in class. I knew the word was racist and bad, but I said nothing. I am, what some people might refer to as, a “white-passing Latina.” You look at me, you see a weta (white girl). In high school I fit in more with the white girls because I looked like them. I felt more comfortable with them because I didn’t feel accepted by the other Latinas, and it’s only now that I realize that this was probably because they did not feel accepted by me either. I knew Mexicans were looked down upon, even in the Bay Area where I was born and raised, which is home to millions of Hispanics, and I didn’t want the burden of being judged for something I had no say in — my race.

This is the overwhelmingly gross privilege of looking white, or more accurately, of not looking like a minority. I am ashamed of this, that I behaved this way as a snobby teenager while my grandfather, with his heavy Spanish accent and dark brown skin, was not given the luxury of accepting or rejecting his heritage. As I grow up I have become invested in embracing and celebrating what my Grandfather has worked so hard to give us, a sense of identity in a country that was not his own.

Women like Sandra Cisneros and Ana Castillo have dedicated their work and lives to reinventing and redefining our culture’s limiting ideologies; this has helped me to better understand the women in my own family. Women like my grandmother, my aunts, and my mother, all of whom married and had children very young and still helped a salvaje woman like me understand the complexities of contemporary identities without abandoning a connection to our history; I do not know who I would be without them.

Teresa Finney is a writer currently living in California. Her work has been featured previously on This Recording. She has affection for her nephews, burritos, and filthy hip hop lyrics. You can follow her on Twitter at @teresatothemax.