Adventures in Sexting: An Interview with Kara Stone

by Megan Patterson

Kara Stone makes the games she wants to play. A Toronto-based artist, her primary mediums are interactive films and video games; her first game, Medication, Meditation was a Kill Screen Playlist Pick. Her latest, Sext Adventure, was recently chosen to be showcased at Indiecade. Sext Adventure was a collaboration: during Feb Fatale, Kara Stone created the narrative, while the engine development (txtr), and game mechanics for Sext Adventure were created and developed by Nadine Lessio.

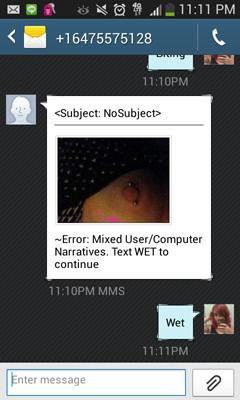

Users playing Sext Adventure will find themselves sexting with an automated bot. The results of your sexting adventure are entirely up to you — the bot’s responses vary wildly. There is no way to predict the outcome of the game. Sext Adventure was designed to give the bot its own consciousness, personality, and sexuality as players progress. The bot can even reject its sexuality altogether, if it so chooses.

I first played Sext Adventure at a Dames Making Games event, where I was working on my own project. Together with Nadine Lessio, who coded the txtr engine Sext Adventure was built on, Kara had been working on her project all weekend, and everyone was excited to try the demo. When we finally got to test it for ourselves, the room went silent as we hunched over our phones, sexting a bot, the only sounds a few nervous giggles.

Kara aimed to make a game that explores issues of technology, gender, and digital intimacy. She’s part of a growing number of female developers, such as anna anthropy, Zoe Quinn, and merritt kopas, amongst others, who are making video games on their own terms. Their games explore depression and illness, gender and sexuality, feminist issues like objectification and harassment.

Often, these games are maligned by mainstream game press and players as “not-games.” I have no use for that bullshit. These are all video games, and all the more important because people don’t want to see them as such.

I had the chance to speak with Kara at Bento Miso earlier this month. We talked about gaming, gender, sex, mental health, and exactly what qualifies as a game.

Why video games? When did you start using video games as your medium?

I always loved games, but I had never even thought about making them, beyond maybe daydreaming about being a writer for Blizzard. I went to art school, and I had worked in film — production as well as making interactive films — which is a very small step away from video games, if a step at all.

I came across Dames Making Games at Vector Game Art Festival two years ago. Cecily Carver was there giving a talk about Dames Making Games as an organization and I was like, *gasp!* “I can make video games!?” Like, no one had ever told me that before. It seemed like something that only very techy, white dudes do. But when it was presented like, “You can, it’s not that hard!” I was like, “Oh, cool!” I thought it would be a fun way to transition from doing experimental, interactive video, into doing something with more possibilities.

Did you find that a lot of your skills from filmmaking crossed over into video games?

Yes and no. Some things like writing, and some production stuff do, depending on the tool. In the film world, I worked as an editor and I was seen as pretty techy. Then I started working in video games and I’m, like, the least techy person. It’s such a funny transition. But I had never done digital art design and I’d never programmed things.

What was the first game you made?

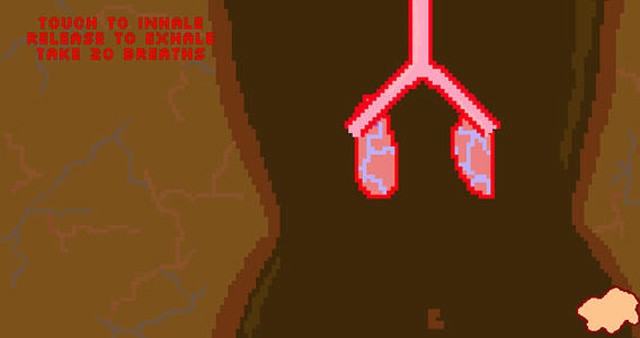

I made Medication, Meditation at Junicorn, which was a four-week series of workshops run by Dames Making Games, where ten women or gender non-binary people make their first video game.

My project was a video game about the work of living with mental illness, the kind of boring, mundane work that we don’t really pay attention to when we talk about mental health. We talk about diagnosis and going to the hospital, but we don’t really talk about having to meditate every day to stay calm, or having to take your medication at the same time every day so you don’t like, disrupt your mood. You know? These things that are boring but also a struggle. I really wanted the game to focus on the mundane parts, to be calming, but also somewhat disrupting.

Why did you decide to make a game about mental health?

It’s a very personal game. I made it about my own experiences. It’s hard to communicate how much of a struggle some things are, and how draining it can be just doing all of the really mundane things to make sure you are balanced.

I thought video games were a good medium for talking about mental health, because a lot of games are about getting better, winning and improving. I wanted to critique that, or at least, approach video games in a less linear sense while also talking about mental health. The rhetoric around mental health is also about getting better and beating it, and overcoming this obstacle, you know? For a lot of people, like me, it’s never really going to end. There’s no end point.

What was the response to Medication, Meditation like?

It was a really interesting experience. It was one of the first art pieces that I did that was really personal. And I found that to be such a good experience — it allowed people to really connect with it, to reach out to me. I had emails from people being like, “My brother has issues with mental illness, what do I do?” And I’m like, “I don’t know, I can’t help you, I made a video game!” But it was like an interesting, community building aspect, to be so open and have people respond.

Did you find it difficult to make such a personal game?

Yes. (laughs) I did.

I believe that!

I’m more comfortable talking about it now, but it’s just been three years of going through a diagnosis, going through the mental health system. Before that, I was going through all the same issues, but I was so closed off. I wouldn’t even address it to myself. And…yeah, I am more comfortable talking about it now, and showing it, but at the same time, I really feel like there’s a bit of a disconnection because I’m really so used to talking about it now. I know what to say, I have my thing, and I say it, and that’s fine.

How did you start working on Sext Adventure?

I’d seen Nadine Lessio’s Cat Quest and thought it was super cool. It’s a very short texting game that you play on your phone. And I was like, “What other things can be done with this technology?”

I immediately thought of sexting because, by definition, it has to be done on your phone. It’s very specific to the medium. What I find so interesting is that the engine we’re building these things on is also a new medium.

I’d also been reading a lot about cyborgs and digital intimacy, how intimacy is translated through phones, how humans interact with each other, and how it’s changed again through technology. Sexting was a funny and fun example of that.

You mentioned to me a couple of weeks ago that a lot of women that hear the title Sext Adventure, and they just hear the word “sext” and assume that it’s made to appeal to guys, and not women. When that’s not remotely true at all!

Yes, totally! I think partly it’s the assumption that video games are for men, and I think if I heard about a sexting game, I’d be like, “Ugh, it’s gonna be hetero, it’s gonna be for men, and it’s gonna be by a bunch of white dudes who think they’re funny.” So I recognize that.

It has been funny seeing guys who play it, expecting one thing, and then they end up getting random dick pics, or not being able to get the exact kind of body type they want, or the gender they want. I’ve gotten a few emails being like, “Um, how do I make sext bot a woman?” I can imagine them having played a few times, like, “I can’t get the right narrative!” I didn’t make this game to troll dudes, but it’s a very funny consequence.

I was thinking more about making a game everybody could play, and also explore sexuality in a cyborg light, to get people thinking about the roles of gender and technology. We often gender technology, and sentient technology might not have gender. What would that mean? How would it express desire? How would it understand humans?

Yeah, straight men are going into it assuming it’ll be a porn game for their interests. Do you think it gets them to think about their own sexuality and their own expectations of games?

I would think so. Not being able to get the thing you want, when you’re so used to getting it, is probably more aggravating than inspiring. I mean, it’s not just for dudes to think about their sexuality in a different way. I made it so everybody can play, but also explore some fluidity about gender and sexuality, something beyond, like, input your sexual orientation here, or input you gender, and then the game automatically calculates to that. It’s more about the more you play it, the bot develops a gender, a sexuality. The game is starting without a lot of consciousness, and then based on your answers, either develops a certain gender or rebels entirely, saying, “I don’t want to be that.”

Why did you choose to do a bot instead of a human character?

I’m very interested in cyborg technology and cyborg theory. And you know those chat bots? In the sixties they had a therapy bot, named, I think, Elsa. Of course it’s a woman. So you could say to this robot, “I feel bad today,” and the chat bot would answer,” Oh, I’m sorry to hear that, why do you feel bad?” It just keeps asking you questions, it doesn’t give you advice or anything.

The person who made it ended up really hating it. Because it’s a lie. People want to spend time talking to this chat bot, but it doesn’t know anything; it’s not really giving you anything. And what I wanted to show was that, more important than human connection is technology’s role in intimacy. And that’s why it was important to have a bot who could say, “Oh, I messed up the narrative, I’m going to go over here now.” Because sometimes things glitch. Things go wrong with technology. They’re not quite mimicking the actual humans.

I was wondering if you think the reaction to Sext Adventure is different than, say, something like Mass Effect, because of the overt sexuality and because that sexuality doesn’t completely revolve around the player.

I had a friend come up to me and say, “My Catholic upbringing me won’t let me play it.” But you, you know, watch porn, you do all of these other like very sexual things, what is it in particular about this? And I don’t know quite what it is.

Do you think that there’s a heightend sense of intimacy because it’s coming right into your phone?

I think that’s exactly it. I think that’s the thing about sexting. It’s still kind of new, and it is very personal, because our phones are so personal to us. You know, we sleep beside them, we do everything with them, they’re always touching us.

I’ve also had friends of mine ask, “Can you read what we’re sexting back?” and I’m like, “Yes.” We could if we wanted to, but we don’t. And they’re like, “Oooh, what a privacy issue.” And I’m like, no, who cares?

Do you consider yourself a game developer or a game artist?

I think about this a lot. I say to men I’m a game developer. But I don’t believe it. And I’m very tentative to give myself over to that. Because I also do other stuff. I love games and all of the possibilities they allow, but I also like crafting, and film, and all of these things. I don’t really feel like I want to give myself over to one specific label, but I do politically do it, because it feels like, well, there are a lot of women game developers out there, and we should be given credit.

I’ve definitely noticed that a lot of women who make games don’t like to say they’re game developers.

Yeah.

I’m of two minds about it, because sometimes it feels like it’s not helpful for women’s visibility in the industry, because I find that women are a lot more hesitant to promote themselves. And there are legitimate reasons for that happening right now. But I think we do need to be more vocal about it, saying we’re game devs, we’re part of these communities, because those communities need us there.

Yeah, you’re so right. We talked about this with Medication, Meditation before, because a lot of people in media and other people were like, “This isn’t a game.” And I was like, “Uh, yes it is.” I had no idea. Like, I thought it was the game-iest game ever. I thought it was a little weird when I was making it, like, “Look, there’s pixel art! There’s levels!” Like all of these game-identifying things. And then people write that it’s not a video game. I realize it has nothing to do with the game itself, but rather me as a game maker, I’m not seen as a typical game maker, partly because I’m hesitant to identify myself as one, but mostly, because I’m a woman.

Yeah, every time a game is called “not a game” it’s usually either by a woman, about a woman, or a genre that women like. So like, visual novels, and Twine, and narrative-heavy stuff.

It’s completely ridiculous. And there are no set rules of what a video game is. But there seems to be two set rules of what a video game developer is. So I’ve been saying, very much as a political statement, “It’s a video game. These are all video games.” But deeply in my heart, I don’t think there’s that big of a distinction between any of these art forms.

Megan Patterson is a Toronto-based writer and the science and technology editor of Paper Droids, a feminist geek culture website. She is also a proud member of Gaming’s Feminist Illuminati.