Lending Fiction to Her Facts: The Legacy of Coco Chanel

by Safa Jinje

My first introduction to Chanel was the sensation of Allure. My mother wore Allure. I distinctly remember the flask shape of the glass bottle; the golden contents I was prohibited from disturbing; the whiff of the scent, like a curtain raising rapture.

Allure isn’t Chanel No. 5, the first fragrance to be launched by French couturier and powerhouse, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, in 1921. A bottle of the storied scent is said to be sold every 30 seconds, and remains one of the most popular and recognizable fragrances of all time. Allure, on the other hand, didn’t make its aromatic debut until 1996, twenty-five years after Chanel’s death on January 10, 1971. I was ten years old.

At the time, I never considered the brand as having a pulse. To me, Chanel was an it: gilded double C’s to be coveted from a distance; sophistication locked behind the glossy pages of magazines; a certain je ne sais quoi, which I believed embodied the spirit of Parisian glamour. It wasn’t until high school, when I developed a more discerning interest in modern history that Chanel, the woman, began to take shape.

Chanel’s life can read like a fairy tale — that is, if the reader only glosses over the surface of her history. The preferred narrative of Chanel biographers is often a rags-to-riches story full of Paris glamor and paramour. And while the Chanel brand continues to benefit from this mythological treatment of its founder’s real life, it is the haute consumer’s desire that keeps this spirit alive.

The Chanel YouTube page features a series of short films, entitled Inside CHANEL, which highlight monumental moments from Coco Chanel’s personal history juxtaposed with the brands’ legendary evolution. Chapter five begins, “Once upon a time there lived a little girl who hid her humble origins all her life and preferred to invent her own legend…”

As one of the most written about figures of twentieth century fashion, Coco, as she was endearingly called by friends, was acutely aware of her eventual place in history. This is perhaps why she obscured and/or redacted the unfavorable details from her life, such as the truth of her origins. In a profile published in the The New Yorker in March 1931, Janet Flanner wrote:

“[Chanel] was one of four motherless little Auvergnate sisters reared on the land by an aunt who did what she could for them, including, fortunately for one, seeing that they learned how to sew.”

Young Gabrielle was actually the second oldest of six children, three girls and three boys (her youngest brother died shortly after birth). An “aunt” didn’t raise her either; rather, nuns in a convent orphanage brought up her and her two sisters after her mother’s death and her father’s abandonment. Coco painstakingly hid the true facts of her origins during her lifetime and is even quoted as once saying: “…If I wrote a book about my life, I would begin with today, with tomorrow. Why begin with childhood? Why youth?” Chanel didn’t believe her early circumstances should define her. She may have been born into poverty, but as far as she was concerned, her success was something she earned.

The fog Chanel spread over her past continues to draw interest. Chanel has been the subject of innumerable films and books: biographies, fictions, and even philosophical musings like Karen Karbo’s “how-to” guide, The Gospel According to Coco Chanel: Life Lessons from the World’s Most Elegant Woman. Karbo’s book uses Chanel’s favorite maxims to construct life lessons from a modern vantage point. One chapter, devoted entirely to cultivating arch rivals, begins with this Chanel gem of a quote: “The only way not to hate azaleas is to cut them.”

In 2011, The New York Times published an article on a war of words brewing among three Chanel biographers. The dispute was centered on Coco Chanel’s Nazi affiliations during World War Two; specifically, how involved she was while living in occupied Paris. Did her connection extend beyond her romantic and social associations? Was she a Nazi agent? A mere collaborator? Was she a lifelong anti-Semite? The Chanel brand was carefully vague in their response to The Times, stating that this biographical row derived from “the difficulties in differentiating fact from fiction”; an ironic but unsurprising statement, considering Chanel’s own propensity of lending fiction to her facts.

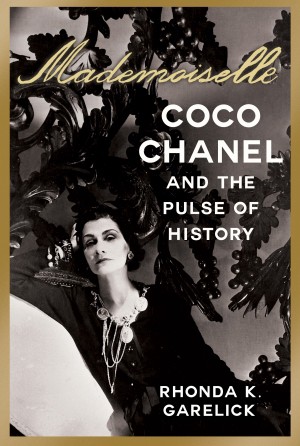

Fashion historian Rhonda Garelick emerges from this murky landscape to offer a new, definitive tome of a biography, Mademoiselle: Coco Chanel and the Pulse of History. The key to Garelick’s success as a Chanel biographer is her hominine treatment of her subject: “To discover the historical,” she writes, “sometimes we must look to the personal.”

History rarely feels personal. Official accounts of the “truth” have a tendency of pushing the messy bits into the margins; and as a result, we look at past events through the black-and-white lens of the victor. The success Chanel achieved in her lifetime was once impossible for a woman, especially so for one lacking an education, money, and a steady footing in society. But as Chanel the woman dissolved into Chanel the icon, her personal struggles and deficiencies were swept out of the official narrative of her brand.

“…‘Chanel’ was once a real person,” Garelick writes in her introduction. “[S]o completely has Chanel the woman blended into Chanel the brand.” Yet Coco had adopted the persona of her brand well before it was inflicted on her. “Chanel confused herself with the female character she had imposed upon all of Paris,” a former employee of hers once remarked. And this is what makes much of what has been previously written about her so problematic: the difficulty, and failure, writers have experienced in separating the woman from the myth.

Each chapter in Garelick’s biography is an expansive examination of Chanel’s life; her romantic and sometimes life-altering influences, like Boy Capel, who not only championed and financed Coco’s ambition, but pushed her to expand her sartorial enterprise; her formative and platonic friendships with creative forces like Misia Sert and Serge Diaghilev introduced Chanel to the realm of artistic patronage, leading to her role as costume designer at the Ballets Russes.

Garelick merges public and private record to present Chanel as a real human, riddled with insecurities and an unrelenting desire for more. The author even suggests that Chanel’s sense of superiority is what drew her to anti-Semitism: “Chanel’s anti-Semitism must be read, in fact, in the context of her keen desire to manufacture a distinguished lineage for herself.” This prejudice was likely formed during her childhood, when the polarizing political climate of the period pitted Catholics against Protestants and Jews. And as Chanel was raised in a convent, where anti-republican sentiments were fused with fears of secularism, she probably absorbed the anxieties floating around her.

Yet Garelick never attempts to justify or excuse Chanel’s behavior and beliefs; rather, she seeks explanations that link cause with effect. Later, in her adulthood, Chanel developed a habit of falling for men with racist politics and nationalist ambitions. After Boy Capel’s death, as Chanel’s youth dwindled, men like Grand Duke Dmitri, a young Russian nationalist who was exiled in Paris after the Bolshevik Revolution, offered the allure of Old World power and pedigree. Garelick writes that both Dmitri and Coco “gravitated toward theories that confirmed their own racial superiority…”

These feelings may also explain why Chanel harbored such a low opinion of the women she made a fortune dressing: “‘A woman,’ she declared, “equals envy plus vanity plus chatter plus a confused mind.” Women symbolized subjugation, everything Chanel had overcome to attain her unprecedented success. In the yesterday of Chanel’s story, she was an abandoned convent girl. Her sexual past likely included brief stints in prostitution. A botched abortion left her infertile. Chanel was a self-made woman, yet despite this, society deemed her unfit for a proper marriage. Chanel’s status allowed her no equals, so she sought to rise above her station and gender, modelling her style and ambitions after white men, because they held what she had long desired: liberty.

The Chanel brand thrives under the muted legacy of its founder. With Karl Lagerfeld at the helm, the fashion house has continued to uphold its mission statement of being “the Ultimate House of Luxury, defining style and creating desire, now and forever.” But the myth of the Chanel brand — the perfectly chic French woman, as polished as the strand of pearls around her neck — eclipses the effort behind the creation, the industrious woman, the creative collaborator, the imperfect being prone to loneliness and destructive lapses in judgment.

The triumph of Coco Chanel and the Pulse of History is its depth. It is easy to get absorbed in the drama of the period, as Garelick weaves the fine strands of Chanel’s life within the larger tapestry of twentieth century European history. But as I put the book down, the image of Chanel that sprung to my mind was no longer the pleasure of a scent. It’s the hard layers of a woman whose life and success oscillated between fantasy and a cautionary tale.

Safa Jinje is a reader and writer living in Toronto. You can follow her on Twitter: @Safajinje