Our Eyebrows, Our Selves

by ManishaAggarwalSchifellite

I’m not sure when I decided that my eyebrows — -thick, dark, and joined — -weren’t considered attractive, but I was a preteen when I realized that I would have to do something about it. When I was 12, I begged my mother to let me get the offending patch waxed. Getting my eyebrows “fixed” was Step One of the makeover process that I just knew was necessary if I was going to be a pretty teenager. In teen magazines and on The O.C. (everyone’s favourite show in 2003), I saw smallness and whiteness celebrated in bodies, in clothes, and in upturned noses. Even Kristin Kreuk, the only image of non-white beauty I remember from that time, was hairless and thin.

I always wondered if my eyebrows could be a little better — -a little more arch, a little less thick, a little further apart. Maybe, by some miracle, my eyebrows would make the rest of me seemed smaller, small enough to fit into a white, blonde, hairless ideal that seemed to be attractive to everyone around me. I understood that to be small, to not offend, was to be feminine, which seemed instrumental to achieving all the milestones of successful teenagehood — -parties, boys, Marissa Cooper’s hipbones.

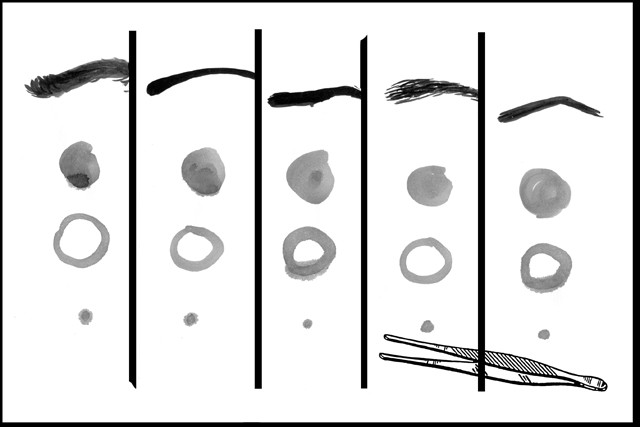

My friend Sheila told me that for her, trying to mold her eyebrows into an acceptable shape was one of the most important problems of her teenage years. “I was going through puberty in the early 1990s, when super-thin pencil eyebrows were the style at that time, and dead-straight hair,” she explained. “Neither the hair on my head nor the hair on my face was compliant with that dominant hair narrative. I remember spending so much time just trying to make my eyebrows fit into this shape that they weren’t going to fit.”

Ronak, an Iranian-Canadian friend, told me about the time she brought photos of her family vacation to show her Canadian friends, including one of her cousin, whose eyebrows joined in the middle. “I thought it was gorgeous,” she says. “But when I was showing my friends [in Canada] the photos, they said “Why does she have a unibrow?” They didn’t understand why anyone would want one.”

At the time, I didn’t understand either. It seemed like social suicide. I knew from watching TV and movies that shaping the eyebrow is an essential part of the feminizing process. From The Princess Diaries to A League of Their Own, big eyebrows are used to show that someone is truly hopeless in their pursuit of femininity — -curable, but not without some work.

After my first fateful trip to the waxer, I thought maybe my problems would be solved. But instead of being relieved that my eyebrows no longer joined in the middle, I was terrified that someone would find out that they weren’t always like that.

Eyebrows have been part of cultural discussions around hair and gender for centuries; references to eyebrow grooming can be found in texts from as far back as the Roman Empire. Claudio Da Soller, a scholar of medieval literature, cites a fourth century poem by the Roman Claudian, who compliments a bride: “How delicate the space between your dark eyebrows!”

In eleventh century Andalusian poetry, ugliness goes hand in hand with “thick, black, [and] joined” eyebrows. This disdain for joined eyebrows are found alongside praise for women with white skin and “delicate” features.

Along the same lines, Chaucer’s epic 14th century poem Troilus and Criseyde refers to the beautiful Criseyde this way: “Except for the fact that her eyebrows joined together, there was no blemish in anything that I can learn of.” Criseyde falls from grace after a sexual encounter — -only then does Chaucer mention her joined eyebrows, equating her sin with her newly noticed ugliness, basically linking her newly discovered impurity with the facial imperfection.

Modernity, the rise of mass advertising, and the entrenchment of conventional gender roles have all played a part in how women think about their eyebrows. In her fascinating book Men without Mustaches, Women with Beards, Afsaneh Najmabadi points out that images of beauty in Iranian art weren’t based on gender difference in the 18th and 19th centuries. During that time, painters depicted beautiful men and women with joined black eyebrows, big green eyes, and generally similar features. The ideal image of beauty in these paintings was often shown to be a male youth (the amrad), who was depicted with a wispy mustache. Women accentuated their eyebrows and facial hair using mascara and other cosmetic products to more closely resemble the boyish image. Najmabadi argues that the desexualization of male homosocial culture led to the erasure of the male youth as the vision of beauty in Iranian art, at the same time that Iranian women were moving into public spheres, interacting with foreign media through magazines and advertisements. By the 1920s, the practice of mascara mustaches had all but vanished, as beauty ideals for men and women emphasized traditional masculinity and femininity in opposition to one another.

Around this time in Europe, there was also a growing medical field that dealt specifically with hypertrichosis, the disease of “superfluous hair.” In the late 1800s, Darwinism dictated that hair was a crucial element in discerning “real” men from “real” women. Kimberly A. Hamlin writes that “while facial hair on women of all races was considered unusual, hirsute white women were considered diseased individuals.” Hirsute women of colour were considered visions of evolution at work.

This scientific take on body hair was brought to mainstream female audiences through women’s magazines and popular advice manuals, which cautioned women to get rid of any excess hair if they were ever going to be happy. This was coupled with beauty advice that advised against looking too “bold” with a heavier brow.

But while women around the world were certainly influenced by Western ideals of beauty celebrating hairlessness and whiteness, they also found ways to negotiate these ideals for themselves. In her article on the Indian “modern girl,” gender scholar Priti Ramamurthy shows that some Indian film stars negotiated patriotism with global fashion through eyebrows. Some were directly influenced by Western fashions, like Patience Cooper, while others maintained a natural shape, like Jahanara Kajjan. Scholars of modern girls write that ultimately, designers and artists were inspired by many different cultures and customs during this time that traveled from East to West and back again.

I’ve been waxing my eyebrows for thirteen years. I’ve come to appreciate that my eyebrows, like most people’s, are not naturally tidy creatures. But I’ve also cared less and less about their possible impact on my life. Instead, I’ve started looking for ways to negotiate the complex relationship. There have been game-changing moments: the first time I saw the Indian film Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, which co-stars Kajol, a beautiful film star who also has a unibrow, the day I stuck a picture of some brown girl singer named M.I.A. to the wall of my college dorm, the first time I saw a photo of Cara Delevigne. These events were evidence that I could find beauty role models outside of what had come before, and I took them with relish.

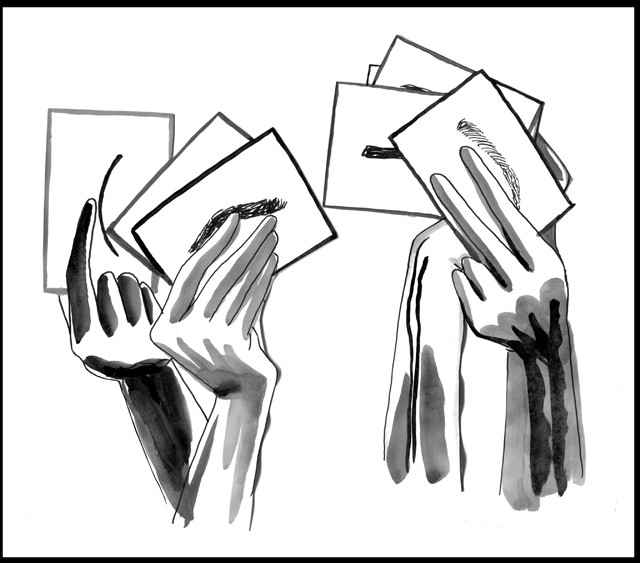

Ronak and Sheila are also finding ways to do their eyebrows on their own terms. Every week, Ronak’s mother threads her eyebrows for her and they spend the time talking and catching up with each other. Sheila went to the same threader for years and found her to be a comforting presence in her life. For me, and for them, these are important ways of navigating our relationships with hair and with other women.

Today, my eyebrow grooming habits are a choice, like putting on makeup or wearing a weird skirt. Instead of going to a fancy place called a “wax bar,” and being embarrassed for showing up with big eyebrows in the first place, I go to a South Asian-owned threading salon, and I get to feel like part of a community of women who get what I’m about.

When I think about myself at 12, trying to figure out how to be good at womanhood, I wish I had seen more diverse examples of beauty around me. Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so bad about not fitting in if I had known about the beautiful people outside of my copies of YM. I wish my preteen self could know that the most important development in my eyebrow acceptance has been talking to other women about how they feel about theirs, that it’s not as shameful as we’re led to believe. Instead of being scared that someone might find out about my eyebrows, I talk about it first. I know that my hair is part of what defines my identity, but not what defines my value.

Previously: On Hair, There and Everywhere, and Intra-Cultural Shame

Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite writes and edits in Toronto.

Georgia Webber is a comics artist living in Toronto, where she is the Comics Editor for carte blanche and the Guest Services Coordinator for the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. She is most often making work about her vocal disability. Georgia wants you to consider your voice. See how at georgiasdumbproject.com.