One of Those Things Nobody Talks About

by Jenna Gabert

It’s funny, the plans we make for ourselves. We think about college, about our careers. About the new person we’re seeing, our future families, what to cook for dinner. And we rarely stop to think about what happens when those plans don’t work out.

My husband and I were one of those couples that other people sitting in fertility clinics hate. While they go to the ends of the earth with invasive treatments and heartbreaking hopes to become parents, we got pregnant on our first try. (I maintain it was the post-hump high five. That extra “we’re awesome!” affirmation somehow translated to reproduction, I’m 94% sure.) We were ecstatic. With David’s family history of miscarriages and fertility problems, we were surprised that it happened so quickly, but we were beaming. And that was nothing compared to the excitement our parents were feeling. Our whole autumn was spent choosing names, deciding on a gender-neutral color scheme (harder than we initially thought!), and impatiently waiting until April 15, when all the things we had imagined about our baby would arrive. Our December 6 ultrasound showed us our perfectly normal, growing-slightly-ahead-of-schedule baby. We wanted to find out the sex, but the technician wouldn’t tell us and said our doctor could reveal her prediction at our next appointment on January 3. We were disappointed, but like all parents-to-be we were just happy our kidlette was healthy. Besides, if we found out before Christmas, we would just tell our families, and they’d wanted it to be a surprise.

I’ve never been one to abuse the health care system. I don’t go to the emergency room unless I’m absolutely positive that something is wrong. And I’d always had occasional headaches (when you live near a mountain range where winds gust at near-hurricane strength for a good portion of the year, a wintertime “Chinook migraine” isn’t out of the ordinary), but what nagged at me was the weird cramping feeling. It crept up and rendered me ineffective for most of December 21. I tried napping, and shifting, and stretching, but nothing made it subside. At 1 a.m. after poring over What to Expect and Google searches, I determined that what I was feeling probably wasn’t normal, and since I had a baby to think about and not just myself, I should probably get it checked. Both my husband and I brought books, thinking we’d need reading material for what was bound to be a horrendously long wait because I was being “one of those people.”

We were taken to Labor and Delivery immediately. I was impressed. I was positive that we were going to have to sit there for three hours only to be handed a Tylenol and told to go home to bed. My jovial state of “wow that was quick” wouldn’t last long.

Two separate nurses tried to find a heartbeat. I still was unconcerned — at my last appointment, my doctor had tried to do the same for a minute or two while my baby squirmed around trying to avoid his little machine at all costs. The nurse asked me: “When was the last time you felt any movement or kicking?” I thought about it. We had been so busy the last few days with Christmas parties and last-minute prep that I hadn’t really had any spare minutes to just sit around and feel my insides being treated like a trampoline. “This morning, I think. I haven’t really been paying attention,” I said, and felt like a bad mom. She told me that my family doctor was on his way to the hospital. This made me feel worse. I didn’t want to drag the man out of bed at 2 a.m., three days before Christmas. That just made me a bitch. I would hate me in that situation. For some reason I still felt like nothing was really wrong. I gave my urine sample, and the lab came to take some blood for testing. My doctor arrived, pressed on my abdomen to locate the unpleasantness that had brought me to the hospital, tried to find the heartbeat, and left to call the lab.

Cue “world shattering feelings” now.

Enter doctor with a grim look on his face. “I’m sorry, Jenna. We think your baby has died. We’ve ordered an ultrasound for when the technician gets in first thing in the morning to be sure. Your blood pressure is elevated, and our first priority as of this moment is to keep it from getting any higher, because right now you’re very much at risk.”

I don’t remember much after that. I remember asking if the blood-pressure medication they were giving me was safe for pregnancy. I remember grasping at the idea that any time there was any shift at all in my belly that it was our baby, and that all the medical professionals were wrong. I remember being told I would most likely be induced later that morning, and that remaining “pregnant” wouldn’t be likely. Looking back now, I’m happy that my nurses were as honest as they were. Unfortunately, I also remember David asking me if he should call our parents. I didn’t want to, thinking that there was still some hope because we didn’t yet know for sure. Watching him break the news to our family members hurt a little. That’s a lie. It hurt a lot. I’m glad he didn’t ask my opinion when all of them asked if they should make the drive down. I would have said no.

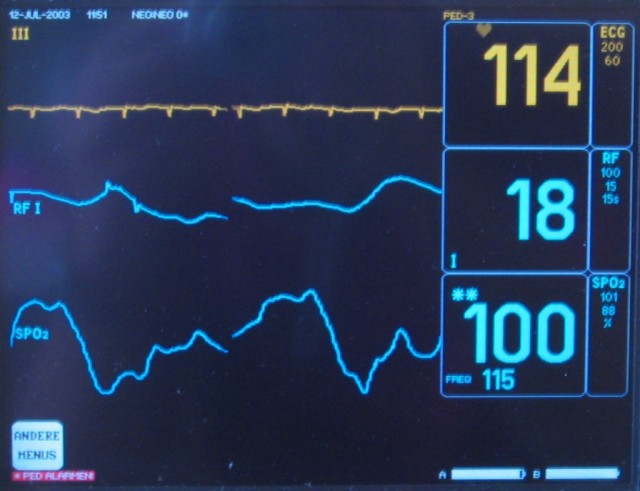

In retrospect there are two moments in my stillbirth experience that will haunt me for the foreseeable future. Yes, labor sucked. What sucked even more was entering the hospital nearly 24 weeks pregnant and leaving with funeral home brochures. But those won’t stay with me nearly as long. I have never felt so (wrongfully, at that) disappointing as I did the moment they wheeled me back into my room after the suspicion-confirming ultrasound. My parents, who had arrived during the night, looked at me with hope, and all I could do was shake my head and break down into sobs. We were heartbroken. All of us. The other moment happened later that afternoon. I was “resting” due to the fact that my blood pressure was threatening to end me. I didn’t know this until later, though everyone else seemed to. Maybe I had forgotten. I was lying there with my mom and mother-in-law on either side, each of them holding one of my hands, which was a miracle on its own considering how many tubes and machines I was hooked up to. The door had been left ajar, and from down the hall we could hear the sound of a woman in active labor, and then the sounds of a newborn and the joy of everyone else in that room. It suddenly hit me that that would not be me. I would have to go through all this work of delivering my baby, and I would never hear those sounds. I would never get to take him home and hold him or love him or fight with David about whose turn it was to get up when he started crying in the middle of the night. I was devastated. All three of us started crying.

The rest of that day is a blur of different people coming in to spend time with me. Most of this time was spent with me apologizing for not being able to give them a grandson or a nephew, mostly because I really didn’t know what else to say. Part of me really did feel guilty. We had asked the nurse to look in the file and tell us what we were having. We didn’t want to pick two names. I took little comfort in knowing that my instincts of “it’s a boy” from the moment I knew I was pregnant were right. It didn’t seem to matter anymore. Nothing did. Even the reassurance from the doctors and nurses telling me that even if I had come in earlier, there was nothing we could have done. It would have just been like watching an accident occur. We wouldn’t have been able to do anything about it, or, even worse, we would have had to make a choice. In some ways I guess we were lucky that we didn’t have to.

At 10:23 the next morning I delivered our son. Because he was two days shy of 24 weeks, he was considered stillborn, and as much as I would have liked to ignore the situation and move on by pretending it never happened, we couldn’t. We had to name him and make arrangements with a funeral home. It was unpleasant at the time, but I’m glad now. I’m also glad that the nurse talked us into seeing him, holding him and spending time with him. I was worried about how he would look. My parents saw him first when I just couldn’t. My dad was right. Aside from being on the small side, he was perfect.

We have some answers about what happened, but not really good ones, and for the most part it remains unexplained which incident caused which. Apparently it just wasn’t meant to be.

The most surprising thing so far has been the aftermath. Losing a child is a strange phenomenon. People you rarely talk to or have lost track of through the years come out of the cracks in your life to tell you that they or someone they know have gone through the same thing. So why does no one talk about it? Yes, I know it’s uncomfortable and weird. I’m not necessarily a hard person to get along with, and yet I’ve had people specifically avoid talking to me because they just don’t know what to say. You don’t have to. No one does, and I don’t think that in the case of stillbirths or miscarriages there is anything you’re supposed to say. Chances are if someone you know has gone through the same thing, they won’t want to talk about it anyway. If they do, all you need to do is lend a patient ear.

The good thing is that each day gets a little easier. Yes, there are moments when I find myself unexpectedly crying, but with time it becomes less frequent. Things will go back to normal. I will always be sad about our little boy we didn’t get to bring home, but I’ve come to realize that it’s not the end of the world. We’ll try again, and I know that when we’re meant to be parents, one way or another, we will be, regardless of whatever we think we have planned.

Jenna Gabert is a substitute teacher. She and her husband are looking forward to trying again soon.