The Best Time I Vomited After Deleting My Twitter

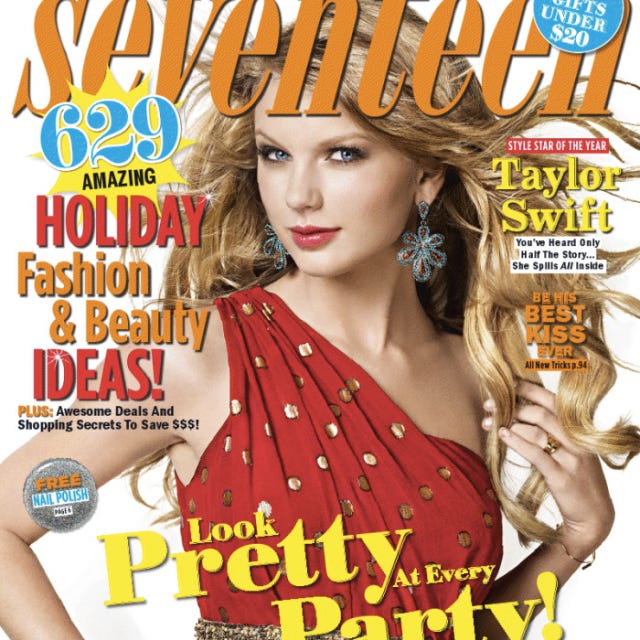

Some months after turning eighteen, by way of opportune timing and a dearth of homework, I became internet famous via a certain charming blog. “The Seventeen Magazine Project” was a sweetly precocious treatise on the oppressive nature of teen magazines and one of the first blogs to really rally behind the person-lives-X-lifestyle-for-X-months construct. It had privilege checking, watered-down third-wave feminism, and the kind of self-aware, coming-of-age narrative that makes leftist media outlets cream their jeans.

Within days of the project launching I had an easy thousand Twitter followers, which doesn’t seem like a lot now, but it was for an average non-celebrity in 2010. In a matter of weeks I went from being a nobody teenager in suburban Pennsylvania to a nobody teenager in suburban Pennsylvania with a moderately successful blog. On some level, my life was transformed. Literary agents flooded my inbox, demanding that I pen a square-format Urban Outfitters coffee table book post-haste. HBO called to ask about optioning my life for TV. Press inquiries piled up; after school I’d take the train into the city to talk with NPR or Q or whoever else had questions about what it was like to be a “role model” for the millennial set. I printed business cards on which I claimed the title “cultural critic.” I was finally living the special-snowflake existence that my elementary school enrichment class teachers had promised.

I took a staff job at an alternative teen magazine and moved to New York to work on my book. Quickly I came to realize that the only thing more fun than actually writing your book was pretending to write your book while you rubbed shoulders with famous people. Over the course of that New York summer, I had drinks with one major public radio celebrity, two minor public radio celebrities, several bestselling authors, three well-known comedians, an okay poet, and the creators of at least two-dozen successful blog projects. The book was never finished. In those conversations, we mostly talked about depression and New York. When the summer ended, I started college in Chicago as “that girl with the famous blog.” In the freshman class, I had more fans than friends. I did schoolwork during the day, blog work at night, and carried an ego the size of the internet itself.

For a while, my physical existence and my internet presence became coterminous. To live as a so-called “internet celebrity” — -that is, to upload the contents of one’s own life in its entirety — -is to engage in a souped-up game of self-actualization. In the course of “real-life,” plots unfold slowly and self-understanding is gained through hindsight and protracted self-reflection. In the game of internet celebrity, players engage in a constant and self-conscious cycle of meaning-making, in which even the most mundane artifacts of daily life can be cast and recast as necessary elements in a continuous and consumable personal plot. The question is not “If the well-plated piece of quiche from the trendy café goes unphotographed, did it ever really exist?” but rather “If the quiche goes unphotographed, what did it ever really mean?” An Instagrammed still life of juice in a mason jar becomes an affirmation of one’s commitment to simpler living. The hashtagged #newhaircut represents the laziest turning of new leaves. On the internet, every new post is an opportunity to steer the narrative in real time. The internet affords us a luxurious new kind of self-making in which “patience” need not be a virtue. Change your profile picture, update your interests — -the new you can be you today.

I’m not saying this newfound sense of control is necessarily a good or a bad development, only that it proved rather difficult for me between the ages of 18 and 21. Late adolescence is already an orgy of meaning-making, and the compounded interest of the public eye only seemed to make things more painful and confusing. Engaging so publicly with the question, “What kind of woman should I be?” felt brazen at first, important even. Media outlets asked me to speak on behalf of a generation. At various points I was named “the future of X” or an “up-and-coming Y.” I still believe that it is important to have worthwhile work, as a woman, to put yourself on display so that others might have the chance to relate to your experience. I’m less comfortable with the idea of teenage martyrs. I was expected to be a role model during a time in my life where I was desperate for role models myself. While other teenagers were out becoming socialized through normal face-to-face engagements, I spent hours alone in my room editing and revising my posts, my image, my brand.

The distinction between internet and reality became increasingly blurred, and to this day is not so clear to me. Of the myriad delusions that internet celebrity perpetuates, perhaps the most prescient for me was that of the unlived double life. The internet has no metropolis. You might sublet in Brooklyn or score invites to NYFW, as I did, but even in these places where blog-types converge, the stories feel discontinuous and the cast of characters is never complete. During my time as a minor internet celebrity, I always maintained the tacit illusion that someday I’d be able to lead my internet life full time. At various points in my existence I fully believed that when the internet revolution eventually came, and indeed it would come, my web friends and I would finally co-habitate in harmony. We would pool our blog money and buy a house in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge. Happiness would be an oft-retweeted street style photo, and Kahlo-esque flower crowns, ordered from Etsy, would never feel contrived or out of place. With the benefit of hindsight, I recognize that I am the only person to blame for these delusions, but I don’t think I’m the only one who fell for it.

During my sophomore year of college, I grew increasingly depressed. I stopped writing and started seeing therapists, eager to search out the answers to existence in a less public forum. I posted manic screeds on Twitter and then deleted them. Fans filled my Tumblr inbox, asking, “Are you okay?” Over the next few years I swapped the circuit of parties and conferences for a tour of psychiatric hospitals. I read my own Wikipedia entry compulsively, contemplating death. To read a crowdsourced summation of your own worth is jarring, especially as a manic, self-obsessed 20-year-old. From every angle the answer was the same: get off the internet.

In January of my junior year I deleted my Twitter, then rushed to the bathroom to vomit. My internet addiction was real and I was going cold turkey. I quit my job at the teen magazine and moved into an Internet-less studio apartment. I took up tangible hobbies and worked to make IRL friends. My life was not immediately better. For months after deleting I still thought in 140-characeter quips. The feedback loop of false affirmation had been broken, and now I had to learn to seek validation from within. Four years after writing that first blog post I’m still not a fully formed human, but it’s comforting to realize that self-actualization can be a slow, private, and gradual process.

Jamie Lauren Keiles lives and writes in Philadelphia.