The Middle-Classism of Teen Movies

by Hayley Krischer

There’s a scene in Allison Anders’ Gas Food Lodging where sisters Trudi and Shade slouch in a truck stop diner booth. Nora, their mother, a waitress, is covering two stations. Trudi (played by Ione Skye) won’t eat because she’d rather starve then risk “smelling like grease and fish.” Trudi hates her town, the trailer park where she lives, and the busboy who spills a soda on her lap. She blames her mother for all of her bad choices, but mostly for her mother’s bad choices in men. She lashes out at her mother and her sister, but really, it’s the world that’s at fault.

The scene captures what we take for granted in teen movies — not the indignant teen, but the frustrated parent struggling to pay bills, who sometimes has to work two shifts, or double shifts, or the graveyard shift. Even in smart teen movies like Mean Girls or 10 Things I Hate About You, there’s endless money for all the fries and Cokes and movies kids want. The kids are sheltered; financial realities simply don’t exist or aren’t addressed. And understandably so — who wants their teen movie filled to the brim with our parents’ problems? Even Charlie Brown dismissed adults as background noise.

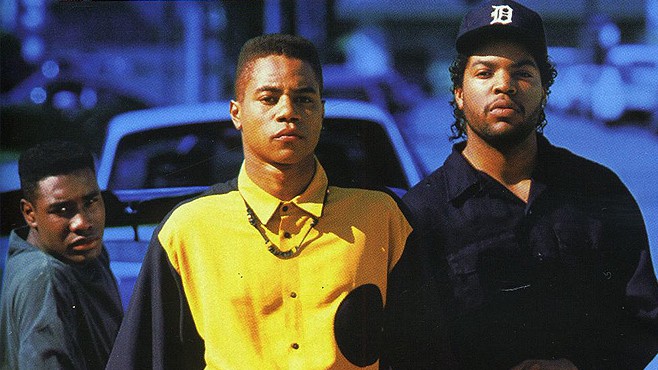

Except teen movies — and movies about teens — in the ’80s and ’90s, like Gas Food Lodging, delved into some heavy socio-economic plots and subplots. There was John Singleton’s groundbreaking Boyz n the Hood about three black teenage boys living in South Central Los Angeles and the demoralizing effect gang life has on them. There was the exhausted single parent in Whatever. There was the no-parent household in The Outsiders. There was the money-is-tight-let’s-move-across-country subplot in The Karate Kid. There was the parent moving to the rich suburb so his kids could go to better schools in Slums of Beverly Hills. There was the rough coming-of-age of three high school seniors in Girls Town, in which the tag line read “This ain’t no 90210.” There was the my-stepfather-is-a-lazy-piece-of-shit-drunk-who eats-all-of-our-food-while-mom-works-her-ass-off subplot in River’s Edge. There was Mi Vida Loca, about Latino teen girls living in gang-riddled Echo Park. There was the I-want-to-be-seen-as-more-than-just-another-black-girl-on-the-subway in Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. Even John Hughes, the king of rich white kids, tackled class warfare with Molly Ringwald’s character in Pretty in Pink, a romantic who lived on the “other side of the tracks,” and Eric Stoltz and Mary Stuart Masterson’s characters in Some Kind of Wonderful were poor artists/drummer/mechanics.

Fast forward today and the middle class struggle is hardly touched on in films about teens. There are 50 million people living in poverty in the U.S., according to the 2013 Census report, but we’ve only seen a tiny sample of contemporary teen movies (Thirteen, Precious, Beneath the Harvest Sky) even attempt to grasp those topics.

This isn’t to say there’s been an absence of heavy plot lines in recent teen movies. There’s been child molestation in The Perks of Being a Wallflower. There’s teenagers with cancer in A Fault in Our Stars. Even the closest contender to socioeconomic truthfulness, The Hunger Games, doesn’t quite stack up: though it’s packed with messages about reality television and oppressive starvation, poverty and extreme wealth, The Hunger Games’ dystopian backdrop feels really far away from some serious economic problems that teenagers in our country are dealing with: the rising costs of higher education, the threat of student loan debt, shrinking incomes, the complexities of health insurance.

So why are the majority of teen movies today steering clear of these socioeconomic problems?

The first reason has much to do with the economy. In the documentary Inequality For All, former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich breaks down the terrible state of the middle class. There’s a Rio Grande-sized divide between the rich and poor, as explained on his website: “The 400 wealthiest Americans make up 62 percent of wealth in America, and the poorest 47 percent of Americans have no wealth.” Last year, a study by the IRS found that between 1993 and 2012, incomes of the one percent grew 86 percent. The incomes of the 99 percent grew six percent. Just a month ago, the Fed reported that the state of inequality grew even wider during the economic “recovery.”

But you already know all this without me having to tell you about those figures — in fact, you probably just skimmed over those figures, didn’t you? The movie industry knows this, too. Middle-class struggling family stories are too familiar. A mom with two girls in a trailer park seems like a trope, the hard-working mom with the drunk boyfriend cliché is played out, the poor kid struggling is too formulaic.

Here’s what happens when people feel behind, when they feel down and out, when they’re sad or scared or concerned: they look for entertainment. They look to the movies. They turn on the TV. They don’t want reminders of how hard life is.

Take a look at filmgoing during the Great Depression. As starving, poor folks sipped their water and ketchup soup, they dished out their 15 cents and they transported themselves to another time — — 80 to 110 million people a week sat in theaters, watching glamorous actresses like Ginger Rogers toe-tap around ballrooms with Fred Astaire. Those pictures were an escape. “People would go into the theater, in this darkened cavern, and it took them out of themselves. They could fantasize about what happened on the screen, about those beautiful stars that existed then,” actor Norman Lloyd told CBS News.

And maybe that concept of glamorous escapism has something to do with why real-life financial situations aren’t depicted in teen movies today. The culture of celebrity excess has never been more popular, though it’s always been something for observers to latch onto. They were even “mindless diversions” in the 1920s, as George Packer keenly wrote in the New York Times. “Celebrities were the new household gods,” he explained. Why? Because people with butlers, and tennis courts and fancy pools had it way better than you.

I don’t think Kanye was entirely wrong when he told GQ that Kim is shaping celebrity culture, because Kim is that “household God” — — everyone wants be friends with Kim, or smell like Kim, or dress like Kim, or have a house like Kim, or have a second home in Paris like Kim, or work out like Kim, or get married like Kim. In droves! And maybe while you’re playing her video game, or watching her show, for a few seconds, you feel like, Yes, if I just bought that lace bib, or the leather skirt from the Kardashian Kollection, I could do Kim. Just for a second.

That has an impact of teenage storylines we see today. Contemporary teen movies mirror that kind of economically “safe” world — -like Kim’s — -because that’s what the movie industry thinks teens expect to see. The average reality show is equipped with the same beige interior, pool with a waterfall out back, Lam or Bentley in the driveway and Bachelor-esque McMansion. Like a Kubrick film or an old Marlboro Red commercial, reality show producers, with their subliminal messaging, engineered a decorating standard: our life is supposed to look like this.

In the ’80s and ’90s, movies and television shows explored storylines on the fray. They were really weird and strangely lit with cryptic-speaking characters and alternative universes — -they weren’t beige and unoffensive. Dialogue in some of my favorite independent films made little sense (see Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise, for an example), but that’s what I craved — an abstract world that made me a slightly uncomfortable. That poked me in the ribs.

Not to mention that in the ’80s and ’90s, independent filmmakers were everywhere. “The indie movement critiqued the dominant culture that Hollywood represented,” wrote UCLA anthropology professor, Sherry B. Ortner in her paper, “Against Hollywood.” During that time, a slew of independent filmmakers created worlds for teens that existed outside of the John Hughes bubble because there was a fundamental disconnect between what was happening in “teen films” — -in which the protagonist struggles but there’s a resolved, happy-ish ending like in Gas Food Lodging — -and “movies about teens” — which the teenage protagonist’s conflict may not be resolved like in Boyz n the Hood — — by indie filmmakers.

There was also a gaping divide between films about white teens and films about teens of color. (In fact, of all the movies I mentioned Allison Anders is the only director who told the stories of Latino youth — and she continues to in directorial stints of Orange Is The New Black.)

Leslie Harris’ Just Another Girl On The I.R.T. told the story of a young black girl living in Brooklyn because Harris wanted her experience to be reflected on screen. “Basically when I started I just wanted to do a film about young black women. That’s a story that hasn’t been told. I started off with two temp jobs, this idea for a script, and no money,” she told Filmmaker Magazine back in 1994. Harris went to the studios, but executives weren’t interested. “They said to make it male — — I heard this!” Harris explained.

That same void drove John Singleton to make Boyz n the Hood. There was no one like him on the screen — no mirror of himself and the kind of raw “odyssey that black boys must undertake in the suffocating conditions of urban decay and civic chaos,” wrote Georgetown sociology professor Michael Eric Dyson at the time. (Singleton was even offered $100,000 not to make it so that an experienced director could take his place.)

Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. and Boyz n the Hood weren’t marketed as “teen movies,” but they spoke to teens, therefore, allowing society a fresh discussion about race, or teen pregnancy, or gang violence, or all of the above — all of which weren’t broadly discussed at that time. It was unheard of.

Go back to that era and you’ll see there weren’t many stories about teenagers of color, period. Sure, there was The Cosby Show, but as I remember it, criticism followed that show for not confronting racism. Critics accused the Huxtables for not being “black” enough, or for writing dad as a doctor and mom as a lawyer because that wasn’t “realistic.” The Cosby Show wasn’t Good Times (a 1970s sitcom about a black family living in the projects). In fact, there were hardly any bad times on The Cosby Show — and if there were, they worked that shit out. “To have confronted the audience about racism would have been commercial suicide,” wrote cultural critic Justin Lewis in Jump Cut.

The Cosby Show existed to broaden the conversation about successful black families. It was, of course, the antithesis to Boyz n the Hood. The Huxtable kids didn’t have to worry about getting shot on the way to school. Police helicopters didn’t drown out their conversations. Crack addicts didn’t live across the street. I don’t know if John Singleton or Leslie Harris could have made a movie about an upper middle-class family back then. I don’t know if they would have wanted to.

The beauty of independent films is they don’t have the marketing-directed dollars, or the must-fit-in-a-box standards that mainstream movies adhere to. They don’t have to be the “black” film or the “teen” film. But what those films were able to do is lend a gritty voice to an unrepresented population. It’s possible independent filmmakers like Singleton and Anders felt the artistic freedom to cover these stories because life during the ’80s and ’90s were economically sound for most people. Their films didn’t represent the majority of the culture — which wouldn’t necessarily be true if those films were made today.

I think that documentaries will be the best record of this time in our country’s history. Documentaries aren’t as hopeful as movies. They’re not as pretty either, but they’ll give it to us straight. They’ll give us the cash-poor, or the crazy, or horrifyingly illegal practices of the filthy rich, or racially-infused violence. They’ll deliver subjects that filmmakers have otherwise been avoiding.

Rich Hill, a documentary and Sundance Grand Jury Winner, directed by Tracy Droz Tragos and Andrew Droz Palermo, is this year’s shining example. In it, the filmmakers (cousins, who visited family in Rich Hill, Missouri, the town the movie is named for) unfold the story of American poverty through the point of view of three teenage boys.

“At its heart, I hope this film is an invitation to empathy, for audiences to think beyond the three kids and their families in the film (who are in a better place now, in part because of their participation in the film and audience reaction). I hope audiences also think of all the kids who don’t have movies made about their lives,” says Droz Tragos, in an interview.

There are so many of those kids. And they all have a story to tell. I hope that we get more chances to hear them.

Hayley Krischer is a writer living in New Jersey.