Power In Numbers: An Interview With Gabriella Coleman

by Sara Black McCulloch

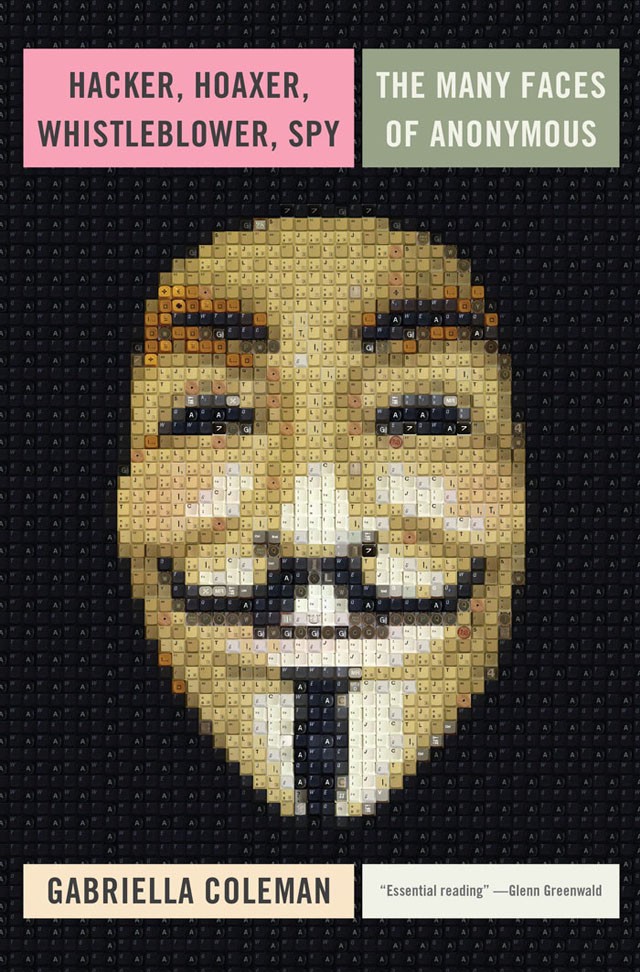

When I first read about Gabriella Coleman’s Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous, I wondered just how she put the book together; how she found people she could trust enough to write about or consult. Whatever the Internet is or isn’t, reporting on it is terrifying — especially when your reputation as a credible academic or journalist is on the line. So many jokes or lies get spread because so many people aren’t careful (or fact check), yes, but also, how can you tell if someone is lying? Especially if you have no other sources to verify, and especially when they’re not standing in front of you.

Coleman is an anthropologist who researches, writes, and teaches about hackers and digital activism. She has written a book on open source and free software, Coding Freedom: The Aesthetics and the Ethics of Hacking. Her research primarily focuses on online collaboration, various forms of digital activism, and surveillance. She is also McGill University’s Wolfe Chair in Scientific and Technological Literacy, researching the relationships between science, technology, and other social, ethical, political, and economics bends. She is one of the very few anthropologists currently studying digital media and culture.

While reading her book, I wondered how much identity factors into trust and analyzing the truth. In Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour, Poitras reads the first letter Snowden sent her (under his codename, Citizenfour) — “Laura. At this stage I can only offer my word,” he tells her, but he’s sure to tell her where he works. In another scene, the Guardian’s Ewan MacAskill asks tells Snowden “I don’t know anything about you,” and when Snowden begins to describe his job, MacAskill stops him, saying “I don’t even know your name.” And yet, MacAskill has flown to Hong Kong to meet this source.

When someone asks if someone or something is a trusted and/or primary source, there’s an implication that the source has a history of being accurate — their word is right and true. But Coleman only had someone’s word. Coleman and Poitras are not comparable in their work, but they did both chase a story that could have died in so many ways.

Sometimes — particularly recently — I feel as though fact-checking protects some shitty people. You don’t have to agree with everything Coleman says or everything Anonymous has done, but there is something to be said about people trying to get some stories heard — especially stories that are consistently swept under a rug.

Coleman recounts the time a black hat computer hack group called LulzSec hacked PBS and posted a fake story about Tupac and Biggie living in New Zealand. It read like a fake news story, but it threatened, in a way, PBS’ legitimacy as a primary news source. It questioned how a lot of readers can blindly trust these established media outlets — and how quickly those lies are spread. Fake facts can be established by some strange power in numbers (repeated stories). I wonder if we all have those instincts that kick in; that flag something in our minds as fake or alarming. Or, are we just at a point now, that, with enough lies spread out there, we stop believing until enough people tell us not to.

Why did you start studying Anonymous?

At first, it was because they were trolling and protesting Scientology. I already had this project on Scientology that I was secretive about because I was scared of Scientology. When Anonymous went from hellraisers to activists I was pretty charmed by that because I was surprised — it felt like a historical accident. And then I just found the kind of world where they valued anonymity and really discouraged fame-seeking was really important and valuable. But I never thought it would become what it did. I always thought it was going to be quirky and esoteric and an accident. When they got involved with WikiLeaks and the Arab Spring, it exploded, and at that point I just had invested a lot of time and was on sabbatical and was addicted to the craziness of it all.

Later it shifted to a more intense paranoia. Sometimes you even regret getting involved in this world because you don’t know what’s going on and it was very palpable. It definitely was a project that tested me emotionally in a way that my last project didn’t do at all.

Throughout the book you discuss how difficult it was carving out a narrative for Anonymous — a lot of this becomes a part of the telling of the story. It also seems that the truth was constantly in flux throughout your research, so how did you figure out what sources to believe, what information to include, and who to believe?

It’s certainly the case that the book I wrote would not have been possible without the arrests of a lot of people. Court documents were incredibly helpful, and a couple of different types of court documents: some that are available and others that had been kind of leaked. And these were really indispensable. So, to give you a good example, Jeremy Hammond — I had interviewed him in prison — and he told a kind of narrative about Stratfor, for example, and also about Sabu and Sabu’s request to hack these foreign countries, right? I didn’t actually have access to chat logs that were part of his case, but they were eventually leaked, and they almost matched verbatim what he said, and that’s in part because Jeremy Hammond, like a lot of hackers, has a bit of a photographic memory.

[To clarify the names here: Jeremy Hammond is a hacker who was sentenced to 10 years in prison for hacking Stratfor and releasing the information through WikiLeaks. Stratfor is a security agency that was hacked by a hacker team called AntiSec (including Jeremy Hammond). Antisec managed to access over 50,000 credit card numbers, downloaded around eight years’ worth of emails, and got a hold of other sensitive material. Sabu is Hector Monsegur, an Anonymous snitch. He was a cofounder of LulzSec, a black hat computer hack group. In 2011, he was arrested and became an informant for the FBI, helping the government arrest members of Anonymous by ordering hacks. Jeremy Hammond was one of these hackers who subsequently got arrested because of him.]

Were some people more trustworthy/reliable than others? How did you assess this?

Some people were. How one assesses that is, often, someone tells you a story, and then you hear the same story from someone else who is not a particularly close friend or interlocutor with the other person, and that’s one way you can start verifying things. It’s also a way to start trusting those other two people.

A good example was one person who was in the IRC #command channel, which was where they were organizing their protests against PayPal and Mastercard. He basically admitted through an interview — but not proof! — that how they got to PayPal was somewhat accidental. It was someone’s side project at first, and then they decided to embrace it. And then someone else who was not particularly close to this person, in part because of his legal case (he had pled guilty and everything had passed), he kind of gave me the logs of that event and it matched up with what he and someone else said. That’s something really hard to fake insofar as I knew a lot of the people (not personally) through their pseudonyms, and people have personalities and linguistic styles, right? And it’s pretty difficult to just invent — though it can happen! — reams and reams and reams of logs. Those were some of the ways that I did it, but certainly if people hadn’t been arrested, I don’t think I could have written the book I wrote.

Also, there are a lot of things in the book where it doesn’t matter if I get to the truth of what happened; in fact that’s precisely the point — that Anonymous operates in secrecy, or tricksterirsm, or the use of deception. And Anonymous may rely more on secrecy, but with any social interaction, you know, you never get to the truth of people’s intentions. You can just judge based on the effects of what’s happening and a lot of the analysis is at that level.

And then there were some really interesting stories that never made it in there because they didn’t relate to analyzing gossip, rumour, or secrecy. And then there were some crazy, unverifiable ones that I just couldn’t include.

You talk quite a bit about the language of deception, and you even mention how Sabu, when he kept saying “we” to you, didn’t imply himself and Anonymous, but himself and the FBI. Were there any other patterns to deception that you noticed?

There was always a lot of suspicion about a lot of individuals. What’s interesting is that eventually AntiSec became suspicious of Sabu (it came really late), and in the meantime another individual had a lot of those accusations directed at him. And I can say this with hindsight, not something I can say I noticed at the time — nor is something I can verify. This is one of the great examples of things where I was like Ha! Was it this or was it not? But I always wonder if there was a Good Cop/Bad Cop scenario, you know? Because it was so perfect how everyone accused this other person and that helped deflect a lot of attention from the informant. That’s always something I’ve returned to, but it’s very hard to verify.

Another interesting thing about how hard it can be to assess things: I was suspicious of Jeremy Hammond a little bit. I liked him and I thought he was really interesting, but he was just so intense online. And there was this time where he said to me “I’m going to delete all these files on Stratfor.” And I was so scared because I thought it was someone who was trying to get me to say something supportive and just nail me — either my reputation or legally nail me, and so I kept it to things like “Oh, that’s very interesting.” I kept it neutral, but I was really freaking out. And when I met him — and honestly, this was one of those situations where some people really match their online personas and other people don’t — and he just struck me as a laid-back, gentle giant. I asked him why he did that? I told him that it scared me and I felt like he was maybe an agent provocateur. And it’s confusing to tell who’s the informant and who’s the authentic one. It gets really mixed up. But I wouldn’t say that’s unique to Anonymous; it happens with offline activism as well.

For the most part, the people in Anonymous seem to put aside their differences for a common goal and work very efficiently.

I know! How does it work? Part of the answer has to do with hackers in general, not even Anonymous, and I’ve seen this in so many different places. I studied Debian and the free software project and I was always amazed at how you had crusty, leftist anarchists — part of the European anti-capitalist scene — working next door to nerdy American hackers who, really, their only politics is free software. And they can work just fine together. And among hackers I just think often it’s the technological…not the goal, but a common sort of technological object that they can work around even when their politics are different. So, when there’s something going on in Tunisia and maybe Mustafa, who is from the region, cares about it, but Kayla is just helping a friend and is interested in a technological issue, right? And within a lot of hacker domains, this is completely fine, because you don’t need to be a card-carrying member of whatever politics to join. [Mustafa Al-Bassam is a former member of Lulzsec, a hacker group and faction of Anonymous. Ryan Ackroyd, one of the six key members of hacking group LulzSec. Online, he performed as a woman named Kayla.]

The second part has to do with the strong friendships that do develop so intensely, in part because online chatting is a really great medium — performing strong bonds — because you’re able to talk in-depth about issues. Unlike Twitter, you know, you can have a real conversation. And you could mix the personal with the political — so I might get on and say I had the crappiest day in the world, that something terrible happened. I mean they had to be careful about which personal details they had to reveal, but nevertheless, there are kind of existential conversations that come into being and then you mix that with the pressing political issues of your day, and in fact, you have a kind of hyper-bonding that can occur.

And then of course, the secrecy element. Secrecy is amazing for creating really strong bonds — you’re in this special club together; everyone’s on the line; you’re all willing to battle for each other at some level. All those conditions do come together and it helps explain how they’re able to do it, when otherwise, it just seems so odd because there’s so much disagreement.

Why do a lot of people get involved with Anonymous — I mean, instead of just hacking? Why do they prefer a collective?

Because hacking is a kind of team sport, especially when it comes to the more complex things, where it really helps for people to have different skills. And with a situation, let’s just say, you’re trying to get information out. You may be able to infiltrate and get the stuff, but then you need another team to help get the information out. Or, for example, it’s pretty — I think I cut this part out — it’s pretty technologically complex to download all the emails. I mean, it’s not rocket science, but nevertheless, to download all the Stratfor emails is not totally straightforward and you need access to someone’s servers and so, for a while, they used someone else’s hack servers, but then eventually they had to transfer it to someone else’s servers and a system administrator provides that, you know? So I think that teamwork is particularly important, but you know, small teams work very well, as opposed to very big teams. You don’t need a whole lot of people and I think that’s why LulzSec was so powerful. It was just about six people, which is kind of that sweet spot where people have different skills.

But post-2013, some of the hacking became more quiet because, well, the very visible stuff was good for getting issues out there or attracting newcomers. It’s bad for operational security, and just doing it very quietly — kind of on your own or just a couple of people — is much smarter in terms of tactical security.

Was Anonymous also challenging how the media perceived them but also how the media spreads misinformation a lot of the time? I mean, some of them seemed very excited when reporters didn’t even bother to fact check their statements, but they also knew this would happen.

Yeah, you know, they seemed to have a very complex and contradictory relationship with the media where, on the one hand, if there was some lie they wanted spread, they could make that happen. And yet, if the media did something wrong, they would point fingers at them. Or they get mad at the media for sensationalizing Anonymous when they are very good at sensationalizing things. And then they also really earnestly worked very closely with reporters. So it’s like anything under the sun, it’s really hard to come up with one narrative in terms of their relationship with the media, but the important thing is they did want a relationship. There are definitely groups that existed that were quiet and this is why I included that little AntiSec critique, where it was AntiSec from the earlier generation, who were just like “This new one isn’t AntiSec — they’re freaking talking to the media. We ignore them. They did not know us. We were an alternative world.” That was not their sensibility and that sensibility does exist in the hacker world — in the past and currently. You know, Hack the Planet (HTP) is a great example of that: They were doing a lot, but there are barely any stories written about them and they hated Anonymous because Anonymous violated that ethic that exists.

Is Anonymous really about politics then?

I think that one way to answer this is that Anonymous, post-2010, was trying to get messages out and the media — whether it’s the mainstream or more specialized forms — is the best way to do it. They needed them.

In a lot of ways, WikiLeaks and Snowden are quite different from Anonymous but all of them are part of this fifth estate, right? Which is working with the fourth estate, but ensuring that the fourth estate kind of follows through on certain things that either they weren’t reporting on or just amplifying.

Is there still a hierarchy within Anonymous, in terms of who gets to run the servers and who gets to make the important decisions? I know it’s a very loosely based system, but is it still structured? Does a small group of people still run it?

Absolutely. I mean there’s a technical elite, and they are the ones who run the infrastructure or have the technical power to hack, but there are a couple of technical elites, like the hackers and then those who run the IRC network. Some crossed over and some did not and there could be a lot of battles or tensions between the two and this is why there’s just not one single node, but a couple of nodes of concentrated power. I would say that organizers and propaganda makers were another one who are really important because they’re the ones who worked with the media, could make the visual material. And then one thing I did realize was that there are multiple teams in existence — well, currently not as many, or a lot of the action is in Latin America — but let’s just say at the height of 2011 and 2012 and part of 2013, there were different teams of people who worked together and it’s only because they were stable and people knew each other and they held a lot of technical power that they were able to pull things off.

Within that technical elite, is it mostly male-dominated?

With the full-on hacking, it’s always men. I’ve never actually met a female Black Hat hacker independent of this research either. I definitely met people who were security hackers — some great female hackers. And then in terms of more tech people, there were definitely a handful of women and there were really important female organizers like darr in Chanology or Mercedes or some people who ran Twitter accounts, but in many of these domains, it was pretty imbalanced. [Mercedes Haefer is an activist who joined AnonOps in 2010. She is facing charges for hosting an IRC where an Anonymous DDoS attack against PayPal was planned.]

Can we talk about how the government is prosecuting a lot of hackers and members of Anonymous? A lot of time hackers are exposing crucial vulnerabilities in security systems and a lot the companies aren’t getting punished as much as these hackers. I mean, they’re getting fined, but hackers are usually looking at higher fines and jail time.

There have been this longstanding problem even outside of Anonymous, where people who are exposing vulnerabilities in these dramatic ways (or just for research) and then they get government attention and then if they’re really hacking, they get in big trouble even though it does, at one level, perform this service, right? And it is certainly the case that a lot of these security researchers and hackers who otherwise didn’t like Anonymous did like LulzSec because it was making their job easier; they really believe that retail and corporations and banks have to have top-knotch security, because if not, it puts the population and their information and identity at risk. But the US has always taken such a hard line against hackers and they’ve never really differentiated between intention or effect. Or they don’t enter it into the equation much. I can’t say that it doesn’t enter into sentencing because pure criminal hacking still does get longer sentencing and I think it’s important to recognize that, but nevertheless the punishments are pretty extreme.

And in the case of Anonymous, although they might have performed this security function, they were truly threatening insofar as they weren’t simply doing that, like they weren’t just pointing out security vulnerabilities for companies. They were infiltrating to get information that could have revealed very politically damning information and this is just really threatening to the status quo. And it was also the case that Anonymous did evade this cyberterrorism frame and so it was particularly important to kind of nip it in the bud and nip it pretty hard and this is one of the reasons why. It’s this historical legacy — they always do it this way, but again, given the fact that this was couched in activism and politics, it made even more threatening.

You mention how you needed to maintain a critical distance, not just for research purposes, but for moral and legal reasons too. At some point, you yourself became a part of the narrative, because suddenly people were asking if they could trust you. You were also kicked out of the channel, which means that you could no longer see what was going on. How did this affect your stance on critical distance in this type of fieldwork?

Anthropology — its fieldwork is based on intimacy and really throwing yourself into the domain you are looking at. Because you can never become a full expert, or full insider — either because you’re not given the full access and because, in other domains, you don’t fully become an expert. So, say you’re studying programmers and biologists or ritual healers, you never can embody their full position. There’s always this outside view. It’s very odd to often be really intimate in an area or place and then, at moments, realize: I’m really not part of this…

But in the end, I had a choice to make. I really did. When you write a book, you can write it in very different ways. I chose a non-academic press [Verso] but still a press that values intellectual work. It’s also a very political press. This wasn’t an accident — I had a bunch of academic presses that were really interested in the book and that would let me write a trade book, but I went with a political press because, two reasons. The two reasons why, in the end, I even went kind of explicitly: I think Anonymous has some really interesting, political things to teach us even if I don’t totally agree 100% with everything: I think that the government is trying to frame them as nefarious cybercriminals and I’m concerned of, you know, feeding that fire or narrative, and in some ways, I have a counter-narrative.

The other thing is that apathy and cynicism are truly a problem and Anonymous was part of this world of trolling. I think that it’s really good that there’s this grassroots space where young people who identify with the Internet can participate in something political and feel attached to it and that’s incredibly valuable as well. They certainly don’t get everything right whatsoever with particular operations, but I do believe in their sincerity.

Sara Black McCulloch is a writer living in Toronto. Mute her on the Internet here.