Hysteria and Teenage Girls

by Hayley Krischer

It was a typical Thursday night at Smash Burger. My friend was with her two sons who were furiously stuffing sweet potato French fries in their mouths. In the booth behind her, my friend saw a young boy who looked a lot like Justin Bieber. So she called her 16-year-old-niece, Kate (not her real name), a Justin Bieber fanatic since she was 12. Kate owns two life-size cardboard Bieber cut-outs — one with a squiggly black mustache drawn on his upper lip by a mischievous cousin — hovering over her bed.

No one knows yet that Justin Bieber was on a religious retreat in my small New Jersey town, at the home of the new pastor to the stars, Carl Lentz. Justin Bieber was just trying to have a burger in peace for about five minutes.

That all ends once Kate walked in and confirmed that, yes, it really was Justin Bieber. She screamed and fell to the ground on her knees. “She had a total nervous breakdown. Crying, hands shaking. She couldn’t move. I had to walk her to the booth,” my friend says. Kate’s screaming was Bieber’s cue to leave, but by then he was surrounded by a swarm of girls. He signed the autograph of a girl in a wheelchair, took a quick picture, left his uneaten food in the booth and bolted.

Kate cradled his empty soda cup in the booth, which is when my friend started filming her. And there she is, this young girl, her face stricken like she witnessed a shooting or an attack, tears and mascara streaming down her face, an expression society would call “hysterical.” Even the counter guy, who I spoke to a few days later, told me: “The Justin Bieber part was weird, but that girl screaming, that’s what made everything explode.” Kate babbled some half-coherent sentences like, “I’m going to die. Oh my God, Justin Bieber at Smash Burger. This is beyond my comprehension. I’m going to kill myself.” And then the phone rings. It’s Kate’s friend. “Alex,” she says, hiccupping through tears. “I’m holding his cuuuuuuup.”

All I wanted to do was hug her when I heard this story — I’ve had my own nervous breakdowns about musicians. What makes girls from the Beatles to Duran Duran to N’Sync to Michael Jackson to One Direction — full on freak out?

Hysteria has always been a women’s issue. The concept goes back about 4,000 years. In Ancient Egypt, hysterical disorders were said to be caused by “spontaneous uterus movement within the female body;” hysterical women who were diagnosed with a uterus too far “up” inside the body were treated with sour and bitter odors near her mouth and nose. If the uterus was too far down, then the putrid odors were placed near her vagina.

In Greek mythology, the Argonaut Melampus treated hysterical women who refused to honor the Greek’s massive phallic symbols and ran away to hide in the mountains from these Goliath-sized penises. During that time, the giant phallus was a representation of God, life and fertility. Melampus cured these virgins, according to research, by urging them to have sex with “young and strong men” because their uterus was being “poisoned by venomous humors due to a lack of orgasms.”

By fifth century B.C., Hippocrates was the first person to use the word “hysteria.” He took the notion of the poisonous uterus to another level — he believed that the “restless” uterus was because of a woman’s “cold and wet” body (as opposed to a man’s “dry and warm and superior” body). He explains that the uterus is a sickly organ — especially if it’s sexually deprived. Writes psychiatric researcher Mauro Giovanni Carta, “[Hippocrates] goes further; especially in virgins, widows, single, or sterile women, this “bad” uterus — since it is not satisfied — not only produces toxic fumes but also takes to wandering around the body, causing various kinds of disorders such as anxiety, sense of suffocation, tremors, sometimes even convulsions and paralysis.”

By the mid 1600’s, doctors like Thomas Willis and philosophers like René Descartes were explaining that hysteria wasn’t because of “bad” lady parts but as a psychological issue; specifically, a psychological women’s issue. For the next 200–250 years, hysteria was defined as part of female “nature,” a hostile “characteristic,” explains researcher Elanie Showalter in Hysteria Beyond Freud. “As a general rule,” wrote the French physician Auguste Fabre in 1883, “all women are hysterical and…every woman carries with her the seeds of hysteria. Hysteria, before being an illness, is a temperament, and what constitutes the temperament of a woman is rudimentary hysteria.” Meaning: women don’t need a reason to be hysterical. We just are.

By the late 1800s and the early 1900s, Freud took on hysteria, theorizing that some of hysteria had to do with traumatic events, but most of hysteria was because of sexual repression. I asked my therapist about this theory, and she told me that hysteria was treated as if there was nothing neurologically going on. “Doctors would take a woman, put her on a table and stimulate her clitoris to orgasm in hopes that she’d be cured of her hysteria,” she explained.

This wasn’t an enviable job though, historians say; doctors were burdened by the chore of bringing their patients to climax, complaining about how long it took. Husbands didn’t want to be sidled with this job of having to bring their hysterical wives to climax either. That’s why the vibrator was invented, writes Rachel P. Maines in her book, The Technology of Orgasm. It was considered a medical instrument “in response to demand from physicians for more rapid and efficient physical therapies, particularly for hysteria.”

It wasn’t until the 1960s that feminists took the idea of hysteria and redefined it — feminist thinkers like Juliet Mitchell believe that hysteria was the first step to feminism, because it was feminine pathology that spoke to and against patriarchy. Hysteria, in other words, has always been a language that women have used to attempt to shut down centuries of mansplaining — and only until the 1960s were they successful at it.

In Salem, Massachusetts in 1692, two girls — 9-year-old Elizabeth Parris and 11-year-old Abigail Williams — began having what was described as uncontrollable “hysterical” fits. They were screaming, crying, moaning, their bodies convulsed and they babbled incoherently. A doctor diagnosed the girls of being under the spell of witchcraft and soon, more girls became “afflicted” with the same symptoms. By the end of that year, 13 women and five men were accused of witchcraft and hanged, according to the Salem Witch Museum.

Though there have been a number of theories as to why this happened; some blame ergot (a fungus) poisoning, others say they were rebelling against their social standing, some historians say the fasting and the obsessive prayer rituals caused tremendous stress. Salem was very religious, it was a small settlement described by historians as “rife with anxiety,” a “crumbling providence.” The girls, in other words, did not just become hysterical out of the blue — there was a lot to be afraid of.

But because it spread from person to person like a social contagion, psychologists explain the hysteria in Salem as conversion disorder. Conversion disorder is a physical manifestation of psychological stress and anxiety. Like, say, the contagious hysteria that goes on at a Justin Bieber concert.

I started researching other cases of conversion disorder. In Monroe, Louisiana in 1952, 165 cheerleaders fainted during a football game. In 1998 in McMinniville, Tenneesse, a teacher noticed a gas-like odor and though the school was evacuated, her symptoms spread to 180 students and teachers. In 2007, in Chalco, Mexico, 600 girls became feverish and nauseated. But the most highly publicized case happened in 2012 in Le Roy, New York, when 14 students (13 girls, one boy), developed symptoms of involuntary twitching and clapping, snorting, muscle spasms and even loss of consciousness.

Two books came out this year based on the Le Roy incident: Megan Abbott’s poetic and creepy The Fever and Katherine Howe’s disturbing Conversion. Because Howe, who also wrote “The Penguin Book of Witches,” is something of a Salem encyclopedia, I spoke with her about the hysteria in Le Roy and if there’s a tie between what happened there and the hysteria surrounding pop stars. And though she was hesitant to name a connection, she did say that there seems to be an expression of excitement and release in conversion disorder.

“Here’s this space in which its almost socially sanctioned to release this kind of tension, especially for adolescent girls who are supposed to control themselves. It’s what they’re supposed to master as a teenager, to control themselves,” she said. Hysteria goes against every grain that adolescent girls learn: be good, be better than the next girl, don’t be loud, don’t be promiscuous. There’s an intensity to hysteria that’s significant, Howe says.

In fact, during her research of the Le Roy incident, she found that one girl described the experience as a “build up of tension which was then released by a verbal disorder and that she felt better if she gave into the physical disorder, the tic,” she said. “There’s a thread that connects it to female anxiety and female emotionalism.”

What is this thread, I wondered? I spoke to Jane Mendle, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Cornell University who specializes in adolescent girls. First, she made clear that the hysteria we see with girls in front of pop stars is not the same as what’s happening in conversion disorder. Conversion disorder is a diagnosable, psychological disorder; in the case of girls and rock stars, the term “hysteria” is really a metaphorical description of their behavior. But “that doesn’t mean that the elements of screaming and crying over rock stars and symptoms of conversion disorder in adolescent females aren’t driven by some of the same underlying principles,” Mendle told me. “There is a strong element of social contagion for both of these things.”

When a group of girls develop conversion disorder, it typically starts with somebody who is at the top of the social pecking order; the Queen Bee or someone close to her. But in the case of Bieber or One Direction hysteria, it may be more complex than just social ranking, because fame is more “valued now than it has been in the past,” Mendle says. A few generations ago, when girls were screaming over The Beatles or The Jackson Five, they didn’t have the option to share that experience on Instagram or Facebook. They shared it with each other, collectively, in the moment. Today’s fame component changes everything. “The majority of tweens and adolescents are extremely interested in becoming famous themselves — it is one of their top priorities for their lives,” Mendle says.

I ask her if this means fame alone would inspire hysteria. “To some degree,” she replied, “because fame as a value and considering Justin Bieber as a part of their lives, even though they’ve never met him, is really what has inspired a lot of this.”

What about conversion disorder? Even though it typically starts with the Queen Bee, there’s still an element that seems to be inspired by wanting attention. Mendle agrees. “One of the things that is most noticeable about conversion disorder is that it tends to occur in people who don’t necessarily command a lot of social attention; by social attention, I really mean society’s attention — in that they are not the focus of their society. And historically and traditionally that’s women,” she said. “So when you look to things like the Salem Witch Trials, these girls were by no means a focus of their community until they developed their physical symptoms. And then they became a center of a town’s narrative in a way they would have never have been able to otherwise.”

Doris Day’s “Que Sera, Sera” was number two on the Billboard chart in 1956. The narrative goes like this: A girl asks her mother about her future, “Will I be pretty? Will I be rich?” The mother replies:

Que sera, sera. Whatever will be, will be.

The future’s not ours to see

Que sera, sera.

The mother isn’t wrong, the future isn’t ours, but when you look at it in the context of women’s place in society the song sums up patriarchal 1950s pretty well. There’s zero agency in it. There’s no question about her passions outside of looking good and being wealthy. Now look at the popular male artists of that same time: the dominators were ultra-macho crooners like Elvis, Frank Sinatra or Dion. As historian Kimberly Cura points out in her paper “The Beatles and Female Fanaticism,” Elvis used his sex appeal and pushy lyrics, Frank Sinatra had his sentimental crooner image and Dion had his womanizing songs like “The Wanderer,” which goes like this:

Oh well, I’m the type of guy who will never settle down

Where pretty girls are well, you know that I’m around

I kiss em and I love em cause to me they’re all the same

I hug em and I squeeze em they don’t even know my name

It’s no wonder girls lost it when The Beatles entered the music scene — they had remarkable differences to these hyper-masculine artists, namely in their lyrics. Adolescent girls went crazy when they heard “She Loves You,” a song that I never really paid much attention to because the chorus, “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah,” was repetitive and annoying. But revisiting the song now and deconstructing it, as well as giving it some historical context, changes it.

She said you hurt her so

She almost lost her mind

And now she says she knows

You’re not the hurting kind

She says she loves you

And you know that can’t be bad

Yes, she loves you

And you know you should be glad, oooh

The Beatles then become this sensitive guy vessel with this song, injecting your stereotypical blockhead male rhetoric with an emotional narrative. Look, you hurt this girl and she knows you didn’t mean it, and she wants to give you a second chance, so why don’t you talk to her, man? “’She Loves You,’ not only speaks of a common real-life dynamic between lovers, but also — and most importantly — places responsibility on the man, not his partner,” explains Cura.

These early Beatles songs created a world where women had freedom from traditional gender roles (like in Doris Day’s “Que, Sera, Sera”). “Women in The Beatles’ songs weren’t depicted as the idealized figures described in typical rock lyrics, but instead were represented fully-formed characters,” writes Cura. This was the key behind the hysteria that surrounded Beatlemania: women and girls were free to express themselves — finally! — because they were understood.

The same has to be said for Morrissey who not only openly embraced a fluid definition of sexuality, but who also wrote from the perspective of masculine sensitivity. His lyrics created a safe place for female fans to scream, to cry, to hand him roses on the stage while he sang. Morrissey reveled and embraced male vulnerability; he exhausted heartbreak. Take the lyrics to “How Soon Is Now:”

You shut your mouth

How can you say

I go about things the wrong way

I am human and I need to be loved

Just like everybody else does

There’s a club if you’d like to go

You could meet somebody who really loves you

So you go, and you stand on your own

And you leave on your own

And you go home, and you cry and you want to die

In this song, he reveals his insecurity and his isolation — he goes to a club and can’t even be consoled because he’s so lonely. Morrissey sings countless songs like this — take “I Know It’s Over” in which he cries, “Oh mother, I can feel, the soil falling over my head. And as I climb into an empty bed. Oh well, enough said.”

Though Morrissey and The Beatles and Justin Bieber have little in common musically, they have everything in common as vulnerable lyricists; Justin Bieber takes the same page out of the Morrissey handbook, especially during his earlier mall days. In his movie Never Say Never he brings up a girl for each performance of “One Less Lonely Girl” and serenades her.

How many “I told you’s” and “start over’s” and shoulders have you cried on before?

How many promises? Be honest girl

How many tears you let hit the floor

How many bags you packed

Just to take them back

Tell me that how many either ‘or’s’

But no more if you let me inside of your world

There’ll be one less lonely girl

The appeal here, like with Morrissey, is that Justin Bieber talks to his subject as if he understands what true vulnerability and heartbreak is about. (And who am I to say? Maybe he does.) These kinds of lyrics allow girls to feel comfortable and secure, giving them permission to engage in hysteria, most noticeably after the introduction of the Beatles. Cura puts it like this: “The Beatles… was the first widespread outburst during the sixties to feature women — in this case, teenaged girls — in a radical context.”

Though lots of critics at the time wanted to write off the hysteria around the Beatles as yet another example of crazy, hormonal girls, or some kind of “social dysfunction,” or as depressive loners — their collective hysteria was really about them stepping outside of their prescribed identities. “Teen and pre-teen girls were expected not only to be good and pure, but to be the enforcers of purity within their teen society — drawing the line for overeager boys and ostracizing girls who failed in this responsibility,” writes journalist Barbara Ehrenreich.

Has much changed? Girls are still expected to act a certain way — but screaming over a pop star gives them a say. It’s like sexual release that’s allowed. Michelle Janning, a sociology professor at Whitman College, who has written about screaming girls, explains this in an email: “This bodily and vocal sexual expression could have two paradoxical interpretations: either a girl screaming at a concert is defiantly protesting girls’ sexual repression in a highly sexualized society, or she is doing so as an unsuspecting part of the larger project to maintain girls’ sexuality as controlled, quiet, and contained.”

But performers like Bieber and Morrissey and The Beatles and Michael Jackson have something else in common: their somewhat androgynous man-boy looks. Adolescent girls see a feminine quality in these kinds of men, sociologists say, that reminded them of themselves. Girls feel safe around more androgynous singers because they’re not pushing the macho stereotype which can be intimidating to a teenage girl. Girls saw the (early) Beatles and Bieber as reflection of themselves, “a phenomenon that would be imitated in the future by androgynous stars such as David Bowie and Michael Jackson,” explains Steven Stark in Meet the Beatles. In the ’80s, hysteria followed Duran Duran and Adam Ant, as Nina Blackwood, one of the early MTV “veejays” explained in an interview with CBS, “The guys were so beautiful. Not handsome in the classic “movie star” way, but actually pretty — lush lips, cheekbones a mile-high, porcelain skin — and they all knew how to apply make-up better than most women I knew.”

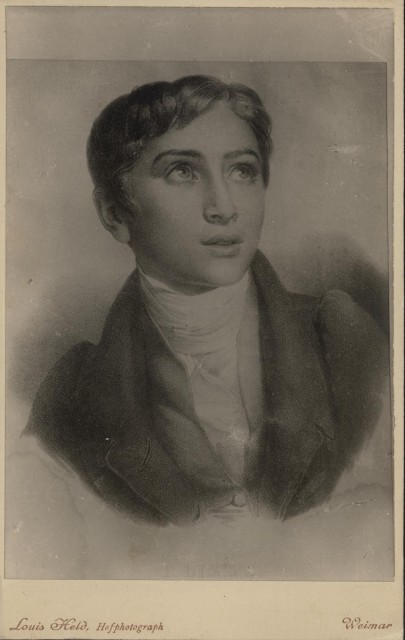

It has to be the same reason women lost it around Franz Liszt, a pianist in Germany in the 1800s — so much that German critic Heinrich Heine, deemed it “Lisztomania.” Liszt also had that feminine quality (more so than other men that time who, at least in old-timey pictures, looked sort of inbred and hairy); Liszt was a Tori Amos kind of performer, historians say, in that he used his body liberally while he played, with “wild arms and swaying hips.” Women tore his clothes, pulled out pieces of his hair and one woman, wrote Alan Walker in a biography, picked up Liszt’s cigar stump, placed it in locket and monogramed it with his initials in diamonds.

The woman’s reaction to Liszt isn’t so far off from Kate’s who collected Justin Bieber’s cup. That plastic cup now rests on her bookshelf, sealed in a plastic zip lock bag.

“People started lining up five days ago.”

“I know they love me even though they don’t know me.”

“Because of you, we’re number one in 37 countries”

“AAAHHHHH!!!”

These are sound bites from the One Direction movie, This Is Us, which is cute and corny with stories about the boys and how they always wanted to be singers, but the primary story is of high-pitched soundtrack of thousands of screaming girls. They’re the screams of pleasure — which is exactly how the neuroscientist Daniel Levitin explains it to the Wall Street Journal. The screaming, he says, is from the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter that allows us to feel pleasure — it’s the chemical in our brain that’s released when we eat chocolate, or when a compulsive gambler wins.

But Levitin’s research also found something else interesting: because the neural pathways in our brains are forming when we’re teenagers, the music that we like as teenagers then becomes hardwired in our brains. It’s not an accident that you still know that pretzel cross-legged move to Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love” you studied a million times when you were 14. That’s not nostalgia, according to Levitin’s research; that’s your brain being hardwired to experience pleasure every time you hear that song.

I couldn’t help but think of the music I went hysterical over as a teenager — I wasn’t a Duran Duran girl in the ’80s. I saved my hysteria for girls, not boys; my heart belonged to Madonna. I was 15 in 1986, the year her album “True Blue” came out — which had some amazing songs like “Live To Tell,” but also some really uninspiring, unremarkable songs like “True Blue.” There was also “Papa Don’t Preach,” which was a departure for Madonna — she changed her whole look from her “Lucky Star”/”Burnin’ Up”/”Borderline” days (which I had memorized the dance moves to as well, though I didn’t completely understand the sexual narrative yet).

In the “Papa Don’t Preach” video she wore boyfriend jeans, had short straight hair, a striped nautical shirt and carried a black motorcycle jacket over her shoulder. My mother called her a Jean Seburg knock-off, but I was mesmerized.

I watched the “Papa Don’t Preach” video on You Tube and remembered those weird arm movements and the dance from that video clearly — then the oddest realization came to me. I’m still influenced by her style from that time, the jeans, the striped shirt, even the motorcycle jacket is currently in my fantasy shopping cart — which, okay, you the jacket has been an iconic staple since Marlon Brando wore it in The Wild Bunch. But then I made another connection. I named my dog, a rescue I just got nine months ago, Trudy Blue. When I started singing the song “True Blue” to her, I couldn’t figure out why — it really bothered me. Why this song?

But now I get it. The dopamine release I experienced as an adolescent girl is still affecting me years and years later. My Madonna hysteria never really waned. When I tell people I follow her on Instagram, they ask me why. And I’m like, “#BitchI’mMadonna,” but the real reason has a lot more to do with chemical engineering.

I wonder what that means for the swarms of Bieber fans like Kate or the One Directioners depicted in their movie. I thought about the years I spent being a hysterical teenage girl, either obsessing over Madonna or later over Morrissey or later REM, or over any of the countless musicians that impacted my life. Science has a great deal to do with hysteria — you can’t ignore the chemical impact of dopamine, but hysteria defined women and girls more broadly than just that; hysteria has been a method of communication in which women have used to separate themselves from men for centuries. I though about that video of Kate in Smash Burger, wondering if she’ll one day look back at it embarrassed, but I hope she won’t. I hope she’ll see it as her individuality shining through, as a way she was able to be true to herself at a very specific time in her life.

Hayley Krischer is a writer living in New Jersey.

Girls screaming via Flickr Commons, Franz Liszt via Wikimedia Commons, and Madonna via Papa Don’t Preach.