How To Build A Fire

by Jessie Singer

For a year, I lived in a trailer in the woods outside Austin, Texas.

Rather, I lived in the remnants of a trailer. Its wheel hubs sat stacked on cinderblocks. The tires, like the windows and all the valuable parts, had long since been stolen by passersby. Any wire that wasn’t copper was left dangling behind.

Electronics hung from the ceiling and spilled out of holes in the façade like the guts of a Tauntaun. They once charged batteries, pumped water and internal toilet tanks, and powered the lights and sounds of the portable home.

But none of that missing electronic equipment mattered. There was no electricity where the trailer sat immobile. There was no running water either.

Lacking plumbing, I installed gutters on every shed and outhouse. The gutters connected to downspouts that poured rainwater into cisterns. With that water, I showered, washed, and nursed the frequent hangovers that come from drinking beer instead of water because all the water tasted like tangy rain.

Solutions for a lack of electricity required a little more work. To eat, to keep warm, to make a pot of coffee: I had to build a fire. In the morning, at night, when I was bored, when I was cold, when I was drunk: I built fires.

At least, eventually I did. First, I had to learn how to build a fire, and that involved learning how everyone else did it first.

The Traditional Architecture of Fire-Building

The Texas woods where my trailer sat on bricks was ten acres, with a swamp and a field and a few spare cacti. I lived there with a flock of chickens and an itinerant man, and shared the acreage with a family of deer, a feral pack of dogs, a number of Water Moccasins and a Wolf Spider infestation that taught me what it really means to be phobic.

There were visitors, too, to my ten acres and my immobile trailer: an aunt from Texas and a best friend from New York City, who both confirmed to everyone back home that I was living in the woods with no electricity. But most often, it was men who came to visit. They were locals who wanted to help till or weed or build a chicken coop. And they all knew how to build a fire.

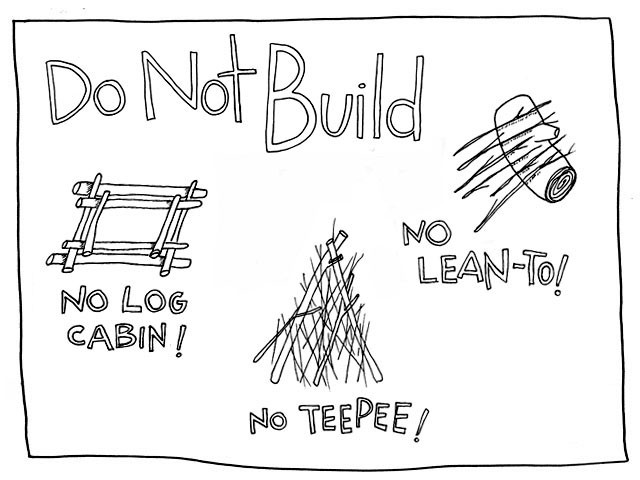

To build a fire, the men had been taught as young Boy Scouts, choose from one of three houses: the teepee, the log cabin or the lean-to.

First you build your house and then you burn it down. The architecture of each construction is highly logical, designed to suck low-lying air into hot coals to feed higher and higher flames. These fires are good ideas. In practice, not so much.

What the Boy Scout Manual doesn’t tell you is what any novice who has tried to build a fire shaped like a house knows: as often as not, these highly-structured fires torch their kindling, then peter out.

With architectural fires, you invest time in construction, but tiny mistakes have dousing results: all the small stuff burns up before the big stuff lights; the whole thing tips over; half your wood is wet on the inside. Whatever little thing goes wrong, you’re stuck with a pile of charred kindling and unimpressed logs.

If you make a new friend and show up for your first coffee date with a schedule for the next ten catch-up sessions and a plan for the birthday party you’re throwing her next year, your new friend is going to think you’re a psychopath. This is why you shouldn’t construct an elaborate wood sculpture and then attempt to light it on fire — because you have no idea what to expect. Fires that are built before they are lit can’t be treated responsively. If it fails to light, you’re out of luck.

How to Build a Fire

My ten acres butted up against another 400 acres of trees, the backend of an unkempt city park. People who need a place to sleep took advantage of the unkemptness, and sometimes their encampments crossed the unmarked border into my ten acres. Occasionally, walking in the woods, I would stumble over someone’s living space. It was mostly older men, the occasional couple, but everyone’s philosophy was to give each other a wide berth — except for the man who taught me how to build a fire.

He was younger than the others, and unabashedly dirty, giving less the impression of hard times as an intentional re-wilding. And he did what none of the others did. He came out of the woods to say hello. I shared my dinner and let him know he was welcome to camp here, to come and go.

He offered to build the fire. It was ablaze in under a minute. Stunned, I complimented his skill. Then he showed me how it was done.

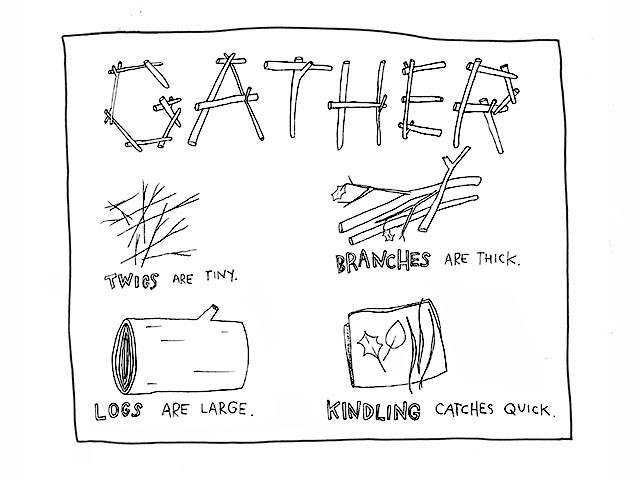

First, gather all your wood. You’ll need four sizes of wood: kindling, twigs, branches, and logs. You will need it all on hand, because you’re going to have to act quickly. Gather your wood from the ground, never cut it from a living tree. While it’s true that softwoods light quicker, hardwoods burn longer and juniper smells awesome when it’s aflame, don’t worry about the type of tree for now.

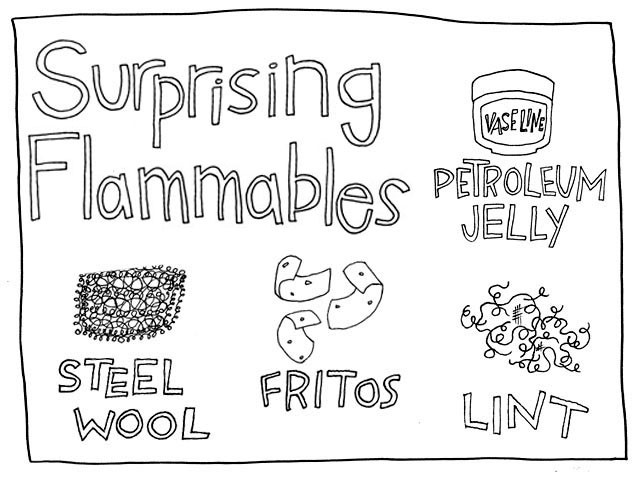

Kindling is tiny stuff that burns quickly. Not sticks, but wood-byproducts that take up a bit more space. Tree bark, brown leaves, brown pine needles and dry grasses all count as kindling. Newspaper is gangbusters. You’ll need three fist-size piles of kindling.

Twigs are the skinny end of branches. The width should range from knitting needle to a pencil. If they’re at all green or don’t snap easily, they’re still too alive to burn. You’ll need three fistfuls of twigs.

Branches should also be brown, not green, and snappy; from the width of your thumb to the width of your wrist. You’ll need two armfuls of branches.

Logs are great if you can find them. A chunk from a tree trunk will burn all night, but it’ll take a fair amount of kindling, twigs, and branches to keep it aflame. If you don’t have any logs, you’ll need double the branches.

Start Small

With all your wood at hand, you’re ready to start a fire. Here is the simple pattern that will govern all next steps and ensure your success: add something to the fire. Once it lights, immediately add something else. This is an Opposite Day game of pick-up sticks — you’re putting them back this time — and the sticks get bigger every few turns.

First, pile your three fistfuls of kindling together. Light your kindling on fire. Then, one by one, add twigs, starting with the smallest and growing larger. When your first twigs catch fire, add more. While you still have some twigs to spare, integrate some branches. Add more twigs between each branch. Then add only branches. Once you’ve added a variety of branches, put a log across the top of your fire.

With a log on your fire, focus on getting that log to join in. Add twigs and branches that bridge from the most aflame part of your fire to the log. Once your log has caught fire, it’s hard to screw up. Add whatever you want to your fire now (not water). If the fire starts to die down, simply add a variety of twigs, branches, and logs.

Hot Crotch

Whenever you add a new twig or branch or log to your fire, place it perpendicular to the last twig or branch or log you added. These crosses are called “hot crotches.” This is the greenhouse of your fire; where it is warmest and where your fire will grow. You get an extra point for using “hot crotch” in a sentence, two if you’re talking to your mother.

If your fire isn’t growing, you’re adding new wood too quickly. If your fire isn’t growing as quickly as you’d like, or some of your branches aren’t catching fire, put your face as close to the fire as you feel comfortable and blow on the bottom most part of the fire as hard as you can. Do it again and again until your fire flares up.

Smokey Says

Do not do this indoors. Don’t do it under a low-hanging canopy of trees. Don’t do it inside a paper factory. Don’t do it at the gas station. Do not leave your fire unattended. Do not build your fire outside of a metal or stone ring. Do not walk away from your fire unless you’re sure it is completely out.

Don’t listen to what they say: Women can pee out fires too. But don’t pee out your fire; it smells terrible. Only you can prevent forest fires.

And the best way to prevent forest fires is to build your fire in a “fire ring.” That’s what the former Boy Scouts told me when I was only weeks deep into a dry Texas summer. There was still New York in my hair, but I had a shovel and a place where I could see large stones half-sunk in the red soil.

It took me an hour to loosen the first rock. I lifted it; heavy and cold, a perfect liner for my future fire pit. Then it bit me.

The sharp pain itched instantly. I drop-tossed the rock a few feet in front of me. The pain shot to my legs. My hands were covered in ants. Where I come from, ants don’t bite. These were crawling up my knees. In search of relief, I rolled in the grass like a dog on a dead thing.

I’d picked a colony of fire ants for the place to put my fire pit, and I was not about to give in. Digging up those ten stones, enough to protect my fires from high winds and rolling brush all year, was the first test of my ability to live in the woods. For weeks, I walked those ten acres in a full-body scatter shot of tiny red pocks, each a tiny merit badge for fire safety.

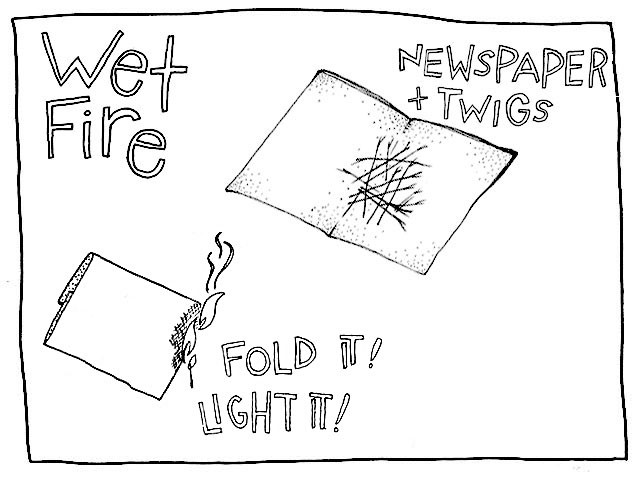

In Case of Rain

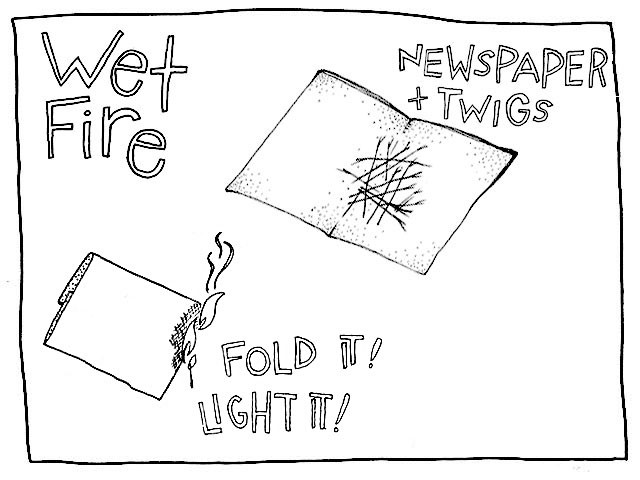

You’re wet. You’re cold. And so is all the wood you can find. You can still start a fire.

Gather some kindling, twigs, and branches. Lay out a big sheet of paper (newspaper rules the day, even if it’s damp). Place a handful of kindling and twigs in the center of the paper. Then, fold the paper into a thick and tidy envelope, completely enveloping the wood a few times over. Make a few envelopes. Place them in the center of your fire ring and place all the other wood you’ve gathered around the edges. Light your envelopes on fire. It may take a few tries.

By the time the newspaper is burned up, you should have a pile of newly dry twigs that are on fire, or at least more likely to light. You can add damp twigs to this fire, and ideally, your fire is hot enough to dry those twigs as they burn. As your fire grows, it will begin to dry the larger branches that you stationed around the edge of your fire. Add them as soon as they feel even a little dry to the touch. Blow on the base of your fire a lot. Fires in the rain require you watch more closely and add wood more frequently.

“You’re going to burn the house down!”

That’s what my mother would yell out the front door when I would sit cross-legged on the porch, lighting infinite matches to melt crayons over the top of a glass of water. The elegant mess of color that resulted — a “memory glass” to be delivered to some girlfriend upon the occasion of their Bat Mitzvah — was just an excuse, and my mother knew it. I liked to play with fire.

In high school, I kept a pile of candles in the corner of my bedroom; I liked to show off, snapping through a flame. I fell for boys who knew how to turn their Binaca into a flamethrower. Art class assignments always ended up requiring burnt edges. Becoming a smoker seemed obvious. In time, the burn became part of me, my fingers calloused and the nerves beneath a little deadened. I could hold my hand close to the fire and grab the cold end of a flaming stick without pause.

Knowing how to build a fire is empowering, but the fire itself is simply power. Archaeologists are convinced that the ability to control fire was the turning point of early human intelligence. It meant more than warmer nights. By cooking our food, we could absorb more nutrients, and our brains benefited.

Learning to build a fire was my turning point, too. Once I could make fire, I was confident I could do anything else living in the woods required.

Anything but this — and this is the most important part of building a fire: If you pick up a stick, and then you realize there’s a spider on it, you throw the stick away and you scream. You throw the stick away and you scream, okay? Screw touching spiders. You’re a fire builder now. No one can take that away from you.

Jessie Gray Singer is a writer, editor and small blowtorch in New York City. She likes to draw.