Georgia O’Keeffe and the Pineapple Fiasco

by Leigh Stein

Whenever I fall in love with someone, I collect the things we have in common, even coincidentally, as evidence we’re destined to be together. Setting aside the fact that she is dead, Georgia O’Keeffe and I share a lot: we were both born in the Midwest, we both moved to New York City, and we both fell in love with the southwest. I’ve memorized so many of her images that today, when I visit New Mexico, the landscape looks to me like she painted it.

Georgia was on my mind a lot last year.

In April, I went to my favorite museum, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, to see an exhibit on her work in Hawaii. If you don’t know anything about her work in Hawaii, there’s good reason for that: it’s not very good. But the museum couldn’t sell tickets to an ugly show, so they paired her work with photographs of Hawaii by Ansel Adams from a similar period.

O’Keeffe went to Hawaii in 1939, on a trip arranged by a Manhattan ad agency. The Dole Pineapple Company paid for her trip expenses; in return, they expected O’Keeffe to create two paintings they could use in advertisements. For two months, she traveled the islands, painting volcanoes and flowers and rain forest. But when she wanted to live in the workers’ village near Dole’s pineapples fields — “all sharp and silvery stretching for miles off to the beautiful irregular mountains” — the company representative told her that would not be allowed: the island’s rigid class system would not tolerate her living among the pineapple pickers. Georgia and the rep got in a fight: she said she was a worker, too; he tried to give her a pineapple as a peace offering. She called the sliced fruit “manhandled,” and left Honolulu for Maui, to go paint waterfalls and beautiful pools.

“Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast, No. 1” is a fine example of what I hate about so many of these paintings: the colors are unimaginative and flat, the shapes are lumpy and juvenile. In other words, this landscape painting is the exact opposite of an O’Keeffe landscape painting. Her talent for distinguishing desert shapes and rendering them so vividly utterly failed her when it came to painting water. Maybe it was too alive. Only the Hawaiian flowers (see “Pink Ornamental Banana”) look okay, probably because they were holding still.

Looking at “Black Lava Bridge” or “Waterfall-End of Road-’Iao Valley,” which is a lumpy mass of emerald green, I felt embarrassed for Georgia. Here, in a museum that honors her finest, spare and elegant work, someone had decided to showcase the drafts, the outtakes, the paintings that have gone unappreciated for good reason. But perhaps I was merely projecting my own fears of public failure — how do we know if what we create is objectively good, until we risk the court of public opinion?

Georgia did the fearless thing that I don’t know how to do: she went to the other side of the world and painted its colors without worrying that anyone would love her any less if she did not get those colors right.

The first time I ever visited the O’Keeffe Museum, I was with my boyfriend Jason. We were living in Albuquerque, where my job was waiting tables at a diner near the highway and his job was reminding me what a great adventure we were having so I wouldn’t hold it against him that I was paying all the bills. I was 23. I bought Georgia’s 639-page biography by Roxana Robinson in the museum gift shop and it became my devotional. I underlined passages from her letters in black ink, like I was trying to teach myself a lesson:

As I see it — to a woman [commitment] means willingness to give life — not only her life but other life — to give up life — or give other life — Nobody I know means that to me — for more than a moment at a time….

It’s always aloneness —

I wonder if I mind.

I minded. And I hated that I did. No matter how manipulative or controlling Jason was, I thought aloneness would be far worse. Even after we broke up I couldn’t quit him; it felt like our lives were destined to collide, as we hooked up in different cities, and reminisced about our great adventure, years after the fact.

In June 2011, I saw him for the last time. We spent an emotional, disastrous week together, and afterwards I finally felt that Georgia strength, that I was not willing to give him any more of my life and that I would live with the consequences. I stopped answering all his calls and texts. I started dating someone kind and gentle.

And then, six weeks later, Jason died in a motorcycle accident.

Like Georgia painting the same door in Abiquiu again and again, this is the story I’ve been telling for the past three years, over and over, from different angles, using every color on my palette of hurt. It feels like I will never finish telling this story. It feels like on the skin around my throat it is written: and then he died. And at parties, when strangers ask, “Aren’t you too young to be writing a memoir?” I always feel surprised and defensive, forgetting the tattoo isn’t actually there.

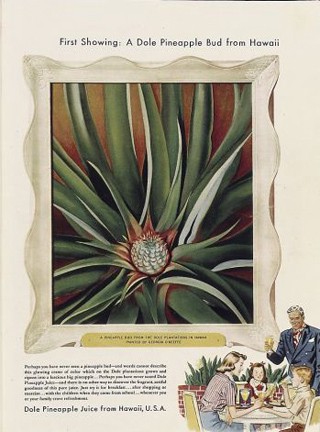

After Hawaii, O’Keeffe returned to New York City in the spring of 1939 and, as promised, sent Dole two paintings they could use in their advertisements: one of a red ginger flower and one of a green papaya tree. But no pineapple? O’Keeffe told them that if she’d known that they’d wanted her to paint a pineapple, she never would have even accepted the invitation.

The company sent her a budding pineapple plant, by air, within thirty-six hours, and she was finally enamored by the spiky green blades enough to paint them.

Then she had a nervous breakdown.

By June of that year, she had lost twelve pounds, was plagued by headaches, and her doctor ordered her to bed rest for six weeks. O’Keeffe wrote a friend that “we might just as well die when it is such a dull life trying to get healthy.” She had to miss her yearly trip to New Mexico, and wrote another friend, “I wish so much to go that I almost wish I had never been there.” It’s hard, even for her biographers, to say whether there was a correlation between her work for Dole and the devastation of her “handsome set of nerves.”

I want to argue that there must be a connection between the lackluster work she painted on the island, the stressful negotiations with the Dole Pineapple Company, and the ensuing depression that kept her from painting for months. But maybe I seek that connection because for the past six weeks I’ve watched my own work fail, my stress is manifest in the hole I’ve chewed through my TMJ orthotic device, and I’m cultivating the characteristic unshaved legs of the depressed.

Georgia, I want to say, I get it.

When her Hawaii paintings were exhibited at An American Place in 1940, O’Keeffe wrote in the catalog, “To formulate the new experience into something one has to say takes time. Maybe the new place enlarges one’s world a little. Maybe one takes one’s own world along and cannot see anything else.” I take these now as her words to me: give it time. Be prepared for your world to enlarge. Put your old world down so you can see.

Georgia is my woman of the year because she is my perennial — my Woman of Every Year. She lived to be 98 years old, and learned to sculpt clay when she became too blind too paint. If I want a life in her footsteps, I still have a long way yet to go.

Leigh Stein is the author of the novel The Fallback Plan and a book of poems, Dispatch From The Future. She is also the creator of BinderCon, a conference for/by/on women writers. Follow her @rhymeswithbee.