Outsider/Insider

by Bethany Lamont

The autistic savants, disabled geniuses, and feel-bad narratives fill our screens and influence our lives. We live in a culture that simultaneously pushes the narratives “I wish I was special like you” and “I would kill myself if I was like you.”

Both statements speak of an othering — specific to that strange, imagined idea of disability constructed by an able-bodied imagination: something special, magical, tragic. The common freak show rhetoric (the kind painted in big bold letters on faux vintage posters) refers to disabled bodies in fantastical terms: as mermaids and monsters. Empathy is difficult if the person in question is a fairytale creature or imaginary friend.

In my experience, I’ve found that the subject of ableism tends to get forgotten in activist discussions. Instead, disability ends up as the sprinkles on a self-righteous social justice sundae.

This is despite the fact that, in the United Kingdom, where I live, disabled people have actually been hit nine times harder by austerity measures than the able-bodied and up to nineteen times harder for those considered “severely” disabled. In his brilliant essay for the Guardian, Aditya Chakrabortty reminds us that hate crimes towards disabled people are rising year after year; they’re currently up by 13% from 2011. 40% of these incidents are violent: people in wheelchairs pushed into incoming traffic, a man asked “what it was like to be blind” before being set on fire. The Washington Coaliton of Sexual Assault Programs reports disabled women are at a significantly higher risk of sexual violence and domestic abuse than able-bodied women.

Because of all these reasons, we need to take a closer look at the way disability is packaged to us in pop culture. Representations of disability in film, television, and music can serve as an indicator of how disabled people are seen in real life, with pop culture products existing as both manifestations of ruling ideologies, and catalysts for belief systems to come. But when the reality of ableism is so brutal, and the projected images of disability so fanciful, how can we cultivate an honest model for disabled narratives? After all, this is a world where some members of the British press openly praise the bravery of a mother for killing her disabled children, one horrifically clear example of how the media evaluates disabled bodies.

Yes, the media we consume does indeed shape how the public imagination perceives disabled bodies and, by extension, disabled lives, and the issue of distancing disabled bodies to myth and magic is certainly a part of this. From avant-garde art to American Horror Story: Freak Show, disability is offered to us as escapism, entertainment, and aesthetics, an exaggerated extension of the occupation of imagination that all art offers us (aside from the obvious fact that the dragons and demons of leather bound books are, y’kno, imaginary, and disabled lives are all too real.)

For a better idea of the relationship between the escapist attitudes of the arts and the reality of ableism, I spoke with Cat Smith, who is writing her PhD thesis at the London College of Fashion on disability and fashion; I personally see fashion as a space for transformation and escapism, a playful occupation of the bodies we live in. So I wanted to talk to her about how disability can become part of the social realities of our lives, and what happens when disability itself becomes the dress up box. She observed:

I think the idea of being a “freak” is really appealing to people who feel like outsiders (so a lot of arty people!). The problem with this is that people want to be freaky or subversive until it actually starts to negatively affect their lives, and where does that leave us who can’t take off the freak costume at the end of the day?

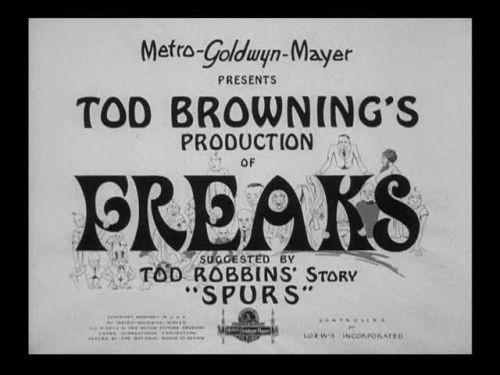

These are the fashion spreads of “sideshow freaks” and able-bodied models in wheelchairs as shock tactics, images unbelievably made for consumption only forty years after there were actual laws to stop disabled people from presenting themselves in public. The 1960s and 1970s sparked the midnight movie revival of Tod Browning’s Freaks, which had a profound influence on both music and the underground comic scene: The Ramones and Frank Zappa both reference it in their work, while Bill Griffith cites Freaks star Schlitzie as the inspiration for his long-running comic series Zippy the Pinhead. I hardly see this as progress, but rather a stubborn cliché that is hard to budge, never shifting, never changing, but oddly, for its able-bodied audiences, never boring.

These films, songs, and comics symbolized a sense of freedom, togetherness, long-haired brotherhood — all while the actors, musicians, and writers would have been unable able to leave their houses. In 1981, Ian Dury wrote his controversial song “Spasticus Autisticus” to protest the United Nations Year of the Disabled Persons:

Hello to you out there in Normal Land

You may not comprehend my tale or understand

As I crawl past your window give me lucky looks

You can be my body but you’ll never read my books.

Not surprisingly the song pretty much ended his career, just like Freaks ended Tod Browning’s mainstream film career. I guess only some kinds of disability are okay.

This brittle occupation of the ‘right’ kind of disability is widespread. In her essay “America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly,” Susan Sontag criticized Diane Arbus’ work for treating disability as a kind of glamor. Sontag argues:

Arbus’s interest in freaks expresses a desire to violate her own innocence, to undermine her sense of being privileged, to vent her frustration at being safe.

She also hits on this trend of alternative ‘community’ when she writes:

Arbus had a perhaps oversimple view of the charm and hypocrisy and discomfort of fraternizing with freaks. Following the elation of discovery, there was the thrill of having won their confidence, of not being afraid of them, of having mastered one’s aversion. Photographing freaks “had a terrific excitement for me,” Arbus explained. “I just used to adore them.

Decades after Diane Arbus and midnight screenings of Freaks, this trend is alive and well in the fandom surrounding the recent television show American Horror Story: Freakshow. Much like how Sontag is certainly not the final word on Diane Arbus, I am hesitant to make sweeping statements of a TV show as messy as American Horror Story. But what we can think about is the fandom and promotion surrounding it. The tagline — and related hashtag, of course — is “We are all freaks.”

To me, this sounds a lot like all that midnight movie stuff in the 1960s and 1970s, a unity through the idea of the ‘freak’, where once again disability becomes a vessel for ideas of escapism and rebellion at the expense of the reality disabled people are facing right now. One quotation from the show is particularly relevant here:

I’ll tell you who the monsters are! The people outside this tent! In your town, in all these little towns. Housewives pinched with bitterness, stupefied with boredom as they doze off in front of their laundry detergent commercials, and dream of strange, erotic pleasures. They have no souls. My monsters, the ones you call depraved, they are the beautiful, heroic ones. They offer their oddity to the world. They provide a laugh, or a fright, to people in need of entertainment.

Because the lived experience of disability does not come from midnight movie reruns, 19th century circus aesthetics, and obscure pop culture references. It comes from existing in a society set up to fail you. We are not all freaks, but we are all geeks, closet fan girls, and professional Netflix browsers, and as consumers of pop culture we have power! Let’s use it to open up a discussion on disability, identify the weird stereotypes that continually crop up, figure out what’s behind this age-old fascination with the freak show, question why some representations of disability are a surefire hit while others are considered ‘bad taste’ and banned outright, and actually listen to what disabled people are saying and what awesome work they are creating. Because we can do so much better than this, and I can’t wait to see it. Shared geekdom over imagined freakdom forever.

Bethany Lamont is the editor in chief of Doll Hospital, an art and literature journal on mental health. She makes art that sometimes appears in galleries, and writing that sometimes gets published in magazines. She also cries in public a lot.