That Battle Is Over

by Hazel Cills

“One of these days everything I write begins the question, ‘What’s wrong with me?’” Norwegian musician and writer Jenny Hval sings on the track “That Battle Is Over.” The track is a soulful, organ-laden echo of a gospel song, in which Hval relays all of the battles that are supposedly “over” for women, from war to breast cancer to eschewing motherhood. The song feels like a response to heavily-branded feminist thinkpiece culture, a response to detractors who deem the movement nonexistent, but also showing the visceral exhaustion towards the problems women face daily.

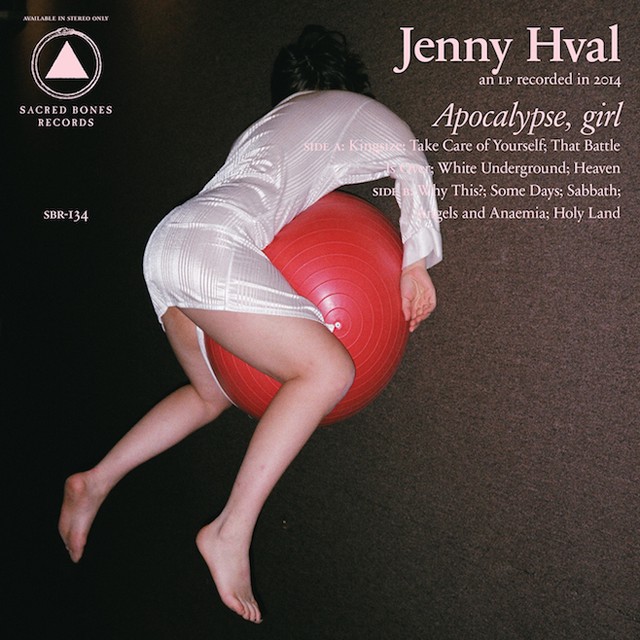

Audre Lorde once said: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” In the past several years the concept of self-care has become an expansive tool for women, at once a means of therapy, redefinition, a pure escape from a society that continually violates female bodies, and more. And Hval’s third album album Apocalypse, Girl, is a dark rumination on one woman’s perceptions of self-care. “What are we taking care of?” Hval asks repeatedly as she navigates visions of her body in a variety of contexts: violent, sexual, divine, political, and, naturally, all of them at once.

What emerges is a document of one artist’s struggle as she tries to make sense of her body and self-doubt in frames provided by mainstream media and contemporary feminism, all the while asking listeners to help her with the answers.

Your song “That Battle Is Over” addresses so many socio-political issues being “over,” like feminism and socialism. What inspired you to write that song?

Most conversations about people saying the battles of the past are over…it’s a very common way of expressing a sort of passive-aggressive distance or rejection of a theme. It’s a way of saying, “oh, you’re just annoying now.” People who always say the battles are over are trying to say that they were never even starting. Women’s rights are always being debated, the abortion issue will never go away, there’s still racism and it’s constant. It’s very obvious that the battles are not over. But a lot of people want to just kill the thought of saying things are necessary in the first place.

I think capitalism has done a good job putting all the blame on the individual rather than seeing a system and a structure. I’m a musician and a freelancer, so I’m not a worker. I’m forced into having my own business because I’m a musician. When you have your own business its easy to think everything is your fault because we have limited rights, compared to somebody with a job, with an employer. That’s the way it’s been going the past 30 years or so, putting all the blame on the individuals. The statement keeps coming back: “The battle is over, we’re all okay in the Western part of the world, so why keep annoying me, you know?” So this song is touching upon that. But it’s not a song that’s a manifesto. I wrote it to sum up what that does to you emotionally, an emotional response to hearing [that saying] all the time in so many ways.

There are many parts of the album where you sing about taking care of yourself, which has often been discussed in contemporary feminism as a radical act. What are your personal opinions on self-care?

Well, I kind of hate it, but I also think there is radical potential in it. I felt kind of like a lonely explorer in it. I watched a lot of films in the recording and writing process of this album and I was inspired by the movie Safe by Todd Haynes, with Julianne Moore, from 1995. I think it’s a sci-fi movie in which the main images in the film have to do with self-care and guilt. It’s a pretty negative take on self-care. But on stage we actually just started playing the album, on tour, and we do a lot of self-care on stage, which I feel is quite a positive act. [It’s] definitely an act that I feel is doing something from a female perspective on stage, which I really love and haven’t been able to do before.

What sort of acts of self-care were you doing on stage?

The last show we did we didn’t have a dressing room so we used the stage as a dressing room. We just let the sound engineer play music where we got changed and put make-up on and got ready and helping each other out getting ready in a kind of ritual.

A lot of Apocalypse, Girl explores you feeling outside of your body. At one point you describe your body as a cushion held up by thin wires or being straightened by metal. And a lot of traditionally celebrated, Western, feminist art across mediums has often been a celebration of the female body, but I think many women artists today who feel alienated by that work are pushing away from it. Would you consider yourself one of those people?

That’s difficult to answer. I’m interested in the body as a musical act. The act of singing is always pushing something out of your body but pushing a new potential body out of your body, something that doesn’t have to look like you in the way you’re meant to see yourself. So I don’t feel that I’m looking at myself a lot on this album, more like I’m trying to go outside of the body to create something or change something that I felt like was broken.

Maybe that’s something that’s self-care: it’s taking care but not as in eating the right foods. It’s more something that’s a potential, a pioneer body or character, something that still is kind of broken but in a way that can also be seen outside the limited view you can have of the body and maybe even the soul, if that word is still valid today from the outside. We have a very limited gaze, I feel.

I guess every point in time has a very limited idea of what it means to look at yourself from the outside, and maybe that’s the potential of all music: to go outside of yourself and look at yourself not with those same eyes.

On your song “Sabbath,” there’s a line where you refer to your body being bound by metal and you sing: “It would be easy to think about submission, but I don’t think it’s about submission, it’s about holding and being held.” Why do you think it’s so much easier to think about submission in that context, in that imagery?

The image came from a dream I had when I was really young but I was too young to feel like I had to right to such a dream. I dreamt that my vagina had braces and that image has stayed with me. It was wonderful, but it was also terrifying; it was both. The terrifying part was that it wasn’t a terrifying thing. I had a dream I was chased by wolves, and that was pure terror, but this dream was different. It was a very common dream of some kind, related to sexuality as a child. You’re dreaming about very sort of mundane images appear[ing] all wrong, sort of sexual and at the wrong place, so it was tormenting and pleasurable at the same time.

When you reach for the first thing that comes into your mind with a lot of body images and things that have to do with sexual pleasure and pain, there’s a need to define it in binderies, but the emotional content is not just that. And for me “holding and being held” is a more creative way of seeing things than always returning to master and slave. I’m not saying that song is about S&M; or something, but it’s about why use those categories when you can use so many things, like emotions or love or expressions, that are much more abstract.

There is a religious, almost choir-like energy throughout this record, in its instrumentals but also in your vocals. On “Heaven,” you sing, “I want to sing religiously.” How much was Christianity or spirituality an influence on this record?

I started taking this weird interest in watching demonstrations of musical equipment. Everybody watches a ton of Youtube videos these days but I started watching them because they were hilarious. I’m not sure if you’ve seen any, you don’t have to, but demonstrations of equipment are awful. A lot of the more expensive or hi-fi equipment you see being demonstrated by people singing Christian songs. I guess it’s because the church people have all the money.

I just got really excited about seeing all this weird spiritual music placed in this awkward, dead space. Someone is just purely demonstrating technical qualities while people are singing about Jesus and gripping their chests because they have to feel it. And this “feeling it” became very interesting to me, this “performance of spirituality” in odd places where you shouldn’t find it, as in an atheist body or in a technical demonstration video.

I grew up in the Bible Belt of Norway, which I guess is nothing like the Bible Belt in America in the case of extremities, but it still kind of mimics it. Going to America a lot I found myself searching for these themes and remembering I grew up in this conflicted space of being a young atheist in a world of religious groups.

You begin and end this album with different ideas about America, particularly connected to ideas of wanting to feel reborn…

Reborn, and unborn, and are they the same.

Was that something that America in particular made you think about or was that something you were asking of larger ideas?

I don’t think I can put the blame on America in general. It’s hard to say because I wrote most of the album before I came to America, but I think I wrote those references afterwards. I was already going into these ideas of spirituality of feeling it in weird spaces because I was always incredibly interested in karaoke and karaoke videos. So everything has to do with signs of authenticity in spaces that are inauthentic. I guess that is America, isn’t it? [laughs]

When did you start getting into karaoke?

I’ve always been interested in it but I’ve maybe performed at karaoke three times in my life? I always dream of doing it but then I never do. I think that’s why I’m interested in it, because I can’t really perform myself. It’s the kind of singing that I can’t do. I was never good at singing in any way than being onstage as an artist so at some point I just started questioning that. Like, why can’t you perform in regular settings like all normal people? [laughs] Why can’t you just do it, when it’s not within a project?

Occasionally, as everyone does, you run into these situations where people sing at weddings or in a karaoke setting in some kind of social setting that’s not a person being on stage. They’re really performing and everyone is quite touched by it, whether it’s a good performance or a felt performance, just a moment. It’s incredibly interesting, the emotional aspect of singing in a social context. I’ve been performing on stage and what you would call an artist for years now, so maybe it was time to question what that is.

You mean questioning what it means to be a performer, that everyone can be a performer in certain settings?

Yes. Maybe I wanted [on this record] to implement more of my feelings about performing when I haven’t created an artist identity or an artists space. I wanted to implement more of what I do when I sing in the shower and when I’m a person off stage and that awkwardness I have with singing offstage. I’ve always felt that’s so weird. Nobody knew I could sing at all until I stood on stage with a band. I always pretended that I couldn’t, I pretended to sing out of key professionally.

I feel like we’re talking about performances having different contexts when they’re performed in different spaces, like the technical construction videos. The stage is clearly an important context to you, but how important is the space or venue where you’re performing to you?

I think there are always two or three spaces happening at the same time. There’s the actual room, which I used to think was incredibly important but I don’t think it is now, I think the space you create on stage is. It’s more of what you bring to it and what the audience brings to it. The audience can have a lot of power in a concert setting whether we like it or not or whether they like it or not. It’s something I spend a lot of time thinking about because I find that a big part of what I do is a response to people. I also think that the space I create by entering the stage and starting to perform is a space I don’t know until it begins and I can’t tell what it will be by the physical dimensions of the room. It’s a space of not knowing, and that’s the space I love.

Hazel Cills is a writer and witch living in New York City.