Fashion To Die For

Collectors Weekly: Why did Marie Antoinette embrace fashion while prior queens had not?

Campbell: It was partly personal and partly cultural. Previously, royal mistresses had been the leaders of fashion. They had the money and the position but no accountability. They could spend as much money as they liked and wear anything they wanted. In contrast, French queens had always dressed magnificently but within the confines of very rigid court etiquette, and they were also answerable to the royal treasury. So in general they followed fashion rather than leading — they didn’t want to rock the boat.

But then Marie Antoinette comes along. Louis XVI didn’t actually have a mistress, so there was a void in the fashion hierarchy. Marie Antoinette was enamored with the vibrant Paris fashion world, as everyone was at the time. Paris had replaced Versailles as the center of society and style, so she wanted to take advantage of the wealth of talent there in Paris, rather than having one official dressmaker who only dressed her, which is what previous queens had done.

Collectors Weekly: How did images of the Queen’s garments spread among the public?

Campbell: Marie Antoinette was used as a model for fashion plates, though they were unauthorized, of course. Some would actually identify her and others just featured a woman who looked a lot like the Queen. This is true with other royal women as well, like her sister-in-laws. It was only at this time, in the 1770s, that fashion magazines began to be issued regularly. Up until then, the images could be found in newspapers or collections of fashion plates.

By the 1770s, you had fashion magazines coming out every 10 days, not just every month like we have now. They needed something new to advertise, and the fashion industry responded to this by issuing new fashions. There were a lot of jokes about how your servant or dressmaker might steal your fashion magazine and by the time you’d get a new one, the clothes were already out of date. Or by the time magazines were delivered to Germany, the styles were out of date because it took 10 days to get there.

Fashion magazines were very widely read, much more than their small circulation would imply — subscribers were limited to the one percent of the one percent, this elite Parisian courtly class that was driving fashion at the time. But because Paris was such a melting pot, laborers and artisans were living side by side with these aristocrats. The magazines were passed around and shared, and even servants got their hands on them. They were all copying these styles to the extent that they could.

There’s a lot we don’t know about how fashion magazines got access to the royal court. In some cases, it’s clear that what they were printing was not actually what was worn because when you look at a surviving dress, it had a different seam here or a different belt there. So in some cases, it’s clear they were either looking at portraits or maybe watching what was being worn from a distance.

However, the editors often made a point of saying a specific outfit was worn by a fashionably dressed woman walking in the Palais-Royal, and places like the Palais-Royal or the Luxemboug Gardens were public domain where people of different classes mixed freely. These magazines were really careful to say when something was actually worn — the duchess wore this, we saw it, and here’s where we saw it. They went overboard to emphasize that this was the latest thing, and they could prove it.

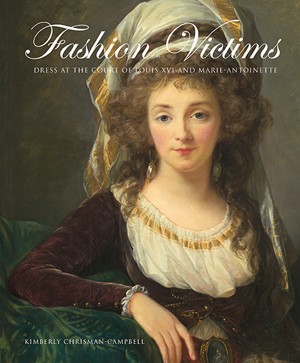

This interview with Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, the author of the new book Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, is fascinating for a lot of reasons, but the above part about fashion magazines in the 1770s being printed every ten days basically blew my mind. Like. How.