When Your Idols Are Assholes

by Alexandra Molotkow

There’s a narrative fallacy wherein we assume the grimiest, most disgusting and/or seemingly violent people are also the sweetest deep down inside — the Bad Boy Forgiveness Strategy, which makes for great fantasies but also inspires girls to correspond with serial killers in prison.

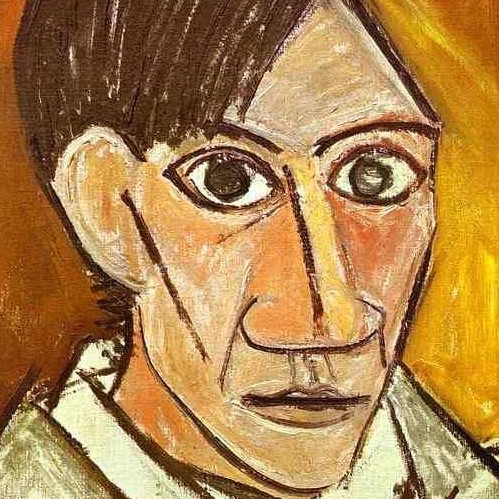

We are at the beginning of a huge shift in the nature of reverence, and what we let power excuse: we are starting to hold our icons accountable for their moral failings (return, as ever, to this bang-on piece by Rawiya Kameir in Fader). John Richardson’s Life of Picasso is a strange thing to read in 2015: the great artist was a “vampire” who sucked the life energy out of his partners and abandoned them when it suited him, but until recently, so what? The ends justified the “means,” as if there were a necessary correlation between dickishness and excellence. That’s the Minotaur Model of Genius: some shining minds require human sacrifice.

We’ve become more critical of our idols, and for much better reasons. As with any major shift in popular attitudes, we sometimes overcompensate — sometimes because it feels like we’ve earned the right, but also because we’re ashamed of having ignored this shit for so long, or we’re scared of the skeletons in our own closets, or because critique turns rapidly into “gotcha.” John Lennon did some awful things in his life, which he got away with for decades, and since his life is of public interest we should talk about the fact that he treated his first wife like trash and neglected his first son. This doesn’t reduce the remarkable work he produced, but celebrities are increasingly human, and people do shitty things, and get taken to task for it. That’s important: shitty things reflect the culture that allows them, and it’s a culture we’re trying to change.

What about the icons who appeal for their disastrousness? Recently, I picked up a copy of Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen, inspired by a mysterious list of rockstar conquests I’ve been returning to online for about a decade. Some entries are interesting (AJ from the Backstreet Boys reportedly “loves to give the ladies backdoor action”), others not so much (Lars Ulrich is a boring lay?), but Jourgensen is “a known drug addict who was named one of the scariest, creepiest rock stars in a Groupie Central poll.” How could I not?

My interest in Jourgensen is a mix of morbid curiosity and the fact that I have a thing for antiheroes, a tendency I’ve been reappraising since it came to light that Kim Fowley, the Runaways manager and classic antihero, raped bassist Jackie Fuchs. To be clear: there’s nothing so far to indicate Jourgensen is a rapist. The throughline is my interest in those who do, or stand for things that aren’t OK, believing conveniently that they probably aren’t that bad.

There’s The Weeknd, and then there’s Al Goldstein, the Screw magazine founder and public access host who, in Choire’s words, “had one of those captivating personalities that it’s easy not to recognize is actually the presentation of mental illness until it all collapses and the interior self is revealed.” His shamelessness led to moments of brilliance, but also plenty of unconscionable tirades, such as this one on Linda Lovelace, quoted on, uh, Rotten.com.

People like Goldstein appeal to us because they’re fucked up, or claim to be, and watching them be themselves is sometimes cathartic: they act on impulses we suppress, or they’re shameless about things we’re ashamed of. But we tend to mistake shamelessness for bravery, and it’s not, and we know that now better than ever.

There’s a difference between storybook and actual evil, but when the story is drawn from life, the division isn’t so neat. I don’t have an answer, so I keep thinking about it.

Národni Galerie, Prague, Czech Republic