Dreaming Of Selena

by Kelli Korducki

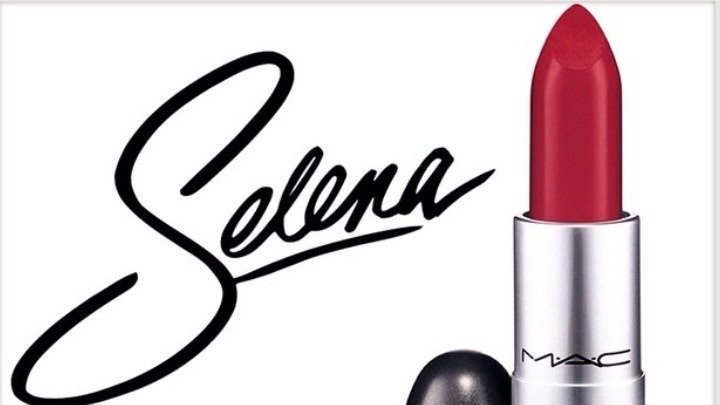

In the middle of September, the family of Selena Quintanilla Perez quietly put out a previously unreleased track by the late artist. Thousands liked and shared the song on Love Selena, a Facebook fan group that welcomes any special occasion to justify its daily tributes, and the music mags sent quick compulsory ripples. But the overall reaction was muted compared to the announcement that MAC would be releasing a multi-product Selena-inspired collection sometime in 2016. The makeup retailer known for its high-profile celebrity collaborations (recently, Rihanna, Miley Cyrus and Lorde, just to name a few) was actively deviating from ultra-topical cover stars for an ultra-Latin artist who died twenty years ago.

A photo posted by M∙A∙C Cosmetics (@maccosmetics) on Jul 16, 2015 at 9:00am PDT

Selena was a Tejano music star in the early nineties who was assassinated by her fan club president in March 1995, just before her 24th birthday. To Latinos within and outside the U.S. she was massive in a way difficult to quantify using our post-Internet-inflated popularity metrics, before Tumblr could make anything feel significant. She, impossibly, ascended to her peak in the hyper-regional genre of the Texas-Mexico border. Jennifer Lopez immortalized her in a 1997 eponymous biopic. Selena Gomez (a Texas-born Chicana) was named in her honor.

When I read the news of the MAC tribute on Facebook, I shared the shit out of it on all the appropriate social media channels. I cried, just a little, but a little all the same. My breath caught and my eyes welled with the same joyous, proud, and vaguely melancholy insistence I recognized when, a few days later, my best friend overseas sent me the first photo of her brand-new firstborn asleep at her boob.

I chalked it up to hormones — menses always lurks, lol — and set my feelings to rest. And it’s taken over a month to really let sink in. Why did I care so much? I spent six or seven weeks holding and turning over the small emotional self-indulgence and passing it from hand to hand.

Selena was a big deal to me as a little kid. I was nine when she died, and her posthumous Dreaming of You album was one of the first records (on cassette, even) I bought with my own saved-up allowance and tooth fairy spoils; I probably paid for it in quarters. Visiting family in El Salvador in July 1995, a friend and I plugged coins into a restaurant jukebox to hear her stupid-catchy “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and whatever else we could find that bore her name. We sang along, clutching our prepubescent chests in a conscious show of telenovela-informed tween mourning. The icon was one we’d equally shared — she, not American and me, not exactly Salvadoran. Selena belonged to us both. Later that summer I would spend a week with an aunt in lily-white western Wisconsin and insist she let me slide my Selena cassette into the tape deck of her little sedan, my pulse quickening in a nervous thump at my neck, the way it always does when I’m about to show something about who I think I am.

We think of identity as that thing that is essentially us, the mitochondrial DNA of our lives’ navigational courses that informs even the way that we sneeze. But identity is also an element of a self met with disagreement or misunderstanding. To grow up Latina in America is frequently the experience of having your personhood assigned to you, your meaning explained back to you.

A part of this can be boiled down to the liminality of the Hispanic-American existence, which is defined by little more than a shared language. When Selena’s MAC collection gets released next year, a record-high 25.2 million Latino-American voters will be preparing to cast their ballots in the fall’s presidential election. Latin America encompasses 20 countries, each with their own distinct histories and cultural cornerstones. All share a history of conquest, but they each also have their own thing going on: the islands with their Afro-Latino booty moves; Mexico’s cowboy mannerisms; the South American cone’s current obsession with digital cumbia. Despite the loose connection, there’s a sense of underlying unity, an in-it-togetherness that’s especially true among those of us in the diaspora. The petty rivalries between Latino nations are broadly, even playfully, accepted as the narcissism of minor difference; patriotism persists, but neighboring achievements are also shared.

Growing up, half of my people hailed from a Latin American country with comparably bland regional cuisine (save for pupusas, obv), blander regional music (sorry fam), and a legacy of prolonged warfare. I had little to brag about on the cultural front; I was raised on the cultural exports of neighbors. There were Dominican bachatas and merengues, Puerto Rican salsas, Colombian cumbias and vallenatos, and more accordion-laden northern Mexican music than you’d want to know — not so different, really, from my Polish-American relatives, because Latin America, too, is a region of immigrants. My rice was oranged with Sazón Goya. I ate frijoles, habichuelas, and gandules in their respective vernaculars.

My experience was, I think, a typical one; the Latino existence is one of mixing and being mixed. We’re elastic, persevering through colonial rape, war-on-drugs-enabled cartel terrors, and not speaking the right language, packing up and moving on and just surviving.

Chantal Braganza, who wrote about Selena here in the spring, took that observation one step further in our recent correspondence:

I think maybe what made her so fiercely loved among people who identified with her was that that hybridity (i.e. a U.S. born artist who crossed over to Latin market, then back to English) was both very much part of how she presented herself and also not her defining trait. That kind of somewhat-uncomfortable explaining so many people with not-straightforward backgrounds feel that they have to do to be understood — whether you’re second-gen, mixed-race, spatially disconnected from some form of heritage or otherwise — didn’t really seem necessary for her.

The 1997 biopic of Selena’s life — again, JLo’s breakout role — is one of the most meaningful pop culture artifacts to women my age. “Anything for Selenasss,” an joke from one of the movie’s more memorable scenes, is an oft-repeated and easily recognizable quotation with a poignancy owed its real-life connections. Released two years after the singer’s death, the film reinforced Selena’s bi-cultural girl power ethos as one that Latina-identifying American girls could adopt for ourselves. We could be strong women. We could have imperfect command of the Spanish language. We could care about our family, but also about achieving big things beyond babies. This didn’t make us any more or any less who we were, or any more or less entitled to the worlds we felt were our right to inhabit. The film, like the artist, offered a rare pop cultural suggestion that “Latina” and “American” aren’t mutually exclusive concepts, that one might in fact be a representation of the other.

The writer Ray Aldaco wrote in his essay “La Chicana Moderna:”

When I think about Selena, one image from the peak of her career always pops into my head: a photograph, originally taken for Maz magazine, in which Selena stands boldly with her hands behind her back, as if at parade rest, proudly flaunting a black-silver-sequined bra/bustier, tight black pants worn high at the waist, classic Latina hoop earrings, and a black hat that Fidel Castro would wear if he had better fashion sense and a taste for shiny embroidery. In this picture, although Selena radiates a strong sexuality, she does so in a defiant, almost militant manor. Her image, in the realms of Chicana sexuality, is a call to arms.

It’s not incidental that Selena was a fashion icon. The looks she wore in public were bold and loud, sometimes garish: bedazzled bustiers and skintight crimson jumpsuits with peekaboo cutouts, all topped with her signature bright red lipstick. Selena’s exterior was a deliberate claim to visibility and sexual power; it’s the continuation of that call to arms that makes the MAC tribute collection so resonant. It says, “If you don’t know about Selena, maybe you should.” But most of all, to state what might be the obvious, it suggests that girls and women and people who look like Selena can and should be the faces of high-end brands. I, for one, will be buying the hell out of that top-shelf lippy.

Previously: Happy Birthday, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez

Kelli Korducki has written for The New Inquiry, Rookie Mag, Hazlitt, and other places on the Internet and in Canada.