“Inside the Massive Rag Yards That Wring Money Out of Your Discarded Clothes”

In the Torah, there’s a decree against garments mixing wool and linen — shatnez, in Hebrew — and likewise, the rag yard has a logic of sameness and difference to its operations. Denim is separated from sweaters. Cashmere is separated from blended knits. Polyester dresses are separated from silk ones. Even the employees are grouped. The Haitian workers in one department, the Hispanic workers in another. There’s a parking lot for the factory workers and another for the office staff. Zweig, however, is an exception with liminal status, capable of code-switching and moving freely through the factory’s various factions.

Zweig was born and raised in an Orthodox Jewish community in Midwood, Brooklyn. He met the rag yard owner’s son at school in Israel where they were both studying, but in his 20s left the fold, dropping out of law school and pursuing a publishing program at Columbia. These days, he’s traded his yarmulke for vintage Hawaiian shirts and lives in Red Hook with a roommate. At Romerovski Corp, he’s allowed to park in the same parking lot as the owners and the other Jewish office workers; his mother is still thrilled he works somewhere where he gets off early on Fridays, the Sabbath.

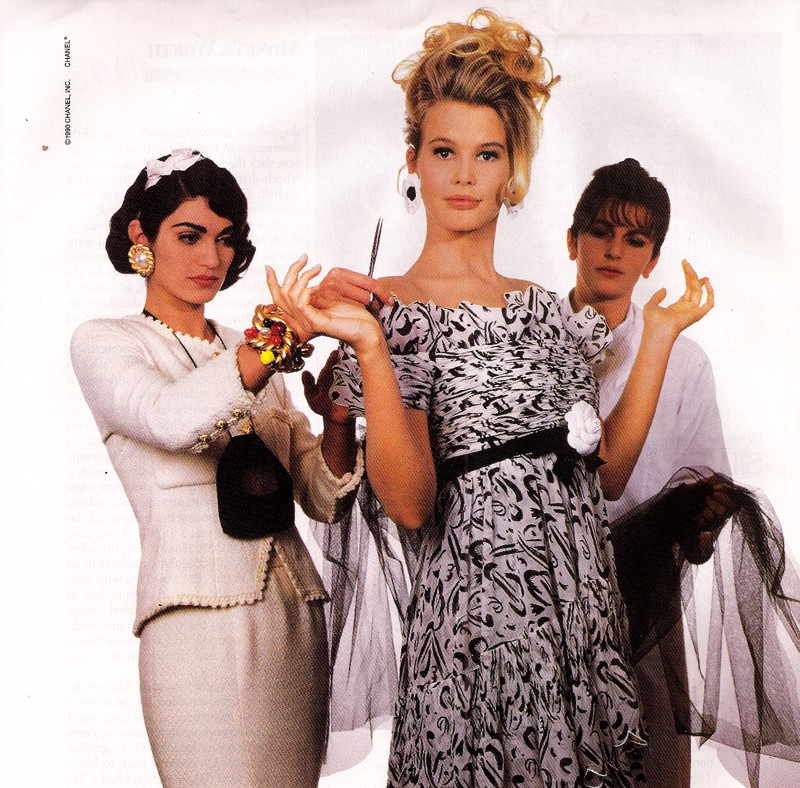

Watching Zweig separate Elie Tahari from Old Navy, faux fur from the real thing, shatnez comes to mind. In the Jewish community, Zweig told me, there are even experts who look under a microscope to certify there’s no forbidden mixing in a garment. But he doesn’t live in that world anymore. For his Orthodox bosses, Zweig’s value is in his knowledge. He knows what’s trending among the fashionistas shopping at vintage boutiques, and therefore what to sell and for how much. After a conversation with the owner’s son, Zweig gestures to a box of clothes he’s curated for a particular Brooklyn vintage boutique: “He wouldn’t have any idea how to sell these.”

I loved Whitney Mallett’s essay about “rag yards” in The New Republic; vintage picking is a fascinating field, both because it reveals so much about the history and usage of clothing and because it’s typically so secretive. The vintage pickers I know work privately and keep their resources close to the vest, pun intended, out of necessity. Every year there is less and less well-made vintage clothing to choose from and, as Whitney details here, more and more poorly made fast fashion. The definition of “vintage” is increasingly…fluid, let’s say, to reflect how quickly that well is running dry, and it’s going to be really fascinating to watch how the loss of true vintage clothing affects the industry as a whole. Read the whole thing here.