The World According To Cintra Wilson

“Fashion is contagious,” Cintra Wilson said at one point during our phone conversation yesterday, and I paused to write it down because I instinctively agreed even though I was unsure why. Fashion is contagious, but like so many people who think critically about an industry that the Joint Economic Committe of the United States Congress values at 1.2 trillion dollars globally ($250 million of which is spent in the United States alone), I’m often torn about whether the contagion is a virus, a cure, or both.

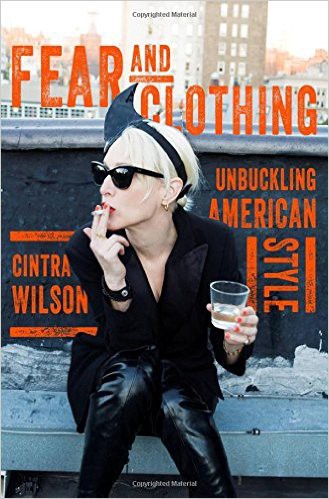

In her new book, Fear and Clothing: Unbuckling American Style, Wilson travels around the U.S. U.S. observing patterns, signifiers, and values across this vast country’s “belts” respectively, the Cotton, Rust, Bible, Sun, Frost, Corn, and Gun Belts. She tries to wear bright colors in Miami, shops for cowboy hats in Wyoming, watches the women leaving the Kentucky Derby replace their five-inch Christian Louboutin heels with ballet flats in the parking lot. It is a travel diary that doubles as a diagnosis: Wilson, as a fashion critic and journalist, always guaranteed her readers complete, brutal transparency on exactly what she thought when she thought it. Likewise, Fear and Clothing shows Wilson assessing what is right, what is wrong, and what is spreading across the landscape of American personal style. We spoke about fashion as a language, as an art, and as a tool for creating fear.

Ok, I’ll start with an easy question: tell us about your book and why you decided to write it.

That’s not an easy question! The new book spanned out of my stint at the New York Times, where I ended up writing a whole lot more articles than anybody thought I would, especially me. I was just a fluke flash-in-the-pan freelancer. I ended up freelancing there for years, from 2007–2011. It was a bumpy ride. I never thought about fashion before working for the Times, and then I realized that it was completely undiscovered intellectual territory. I mean, people have discovered it, but I didn’t know how rich of a topic it was. I was very surprised by the amount of information and the amazing stuff you can extrapolate from fashion.

There’s one passage in the book where you tried on a Balenciaga jacket. You wrote:

On one of my early Critical Shopper excursions, I had what I figure was my Rosetta Stone moment, in the Balenciaga boutique. Professional fashionisti had been calling the designer Nicolas Ghesquière a genius for some time. I’d seen photos of the Balenciaga line, but I didn’t really get what the big deal was.

Then I saw the Jacket, in the flesh (or the wool, as it were).

It wasn’t something I’d ever want (I wrote) — not my style at all. It was a classic bouclé jacket — a short, fitted, nubby wool thing that a First Lady might wear, by Chanel or Adolfo — but it had pow- erful differences. It had been toughened up: it was tighter, thicker, more compact. The interwoven wools were black and white, with loud sparks of fluorescent primary color going “Bang!” inside.

When I tried it on, the collar was surprisingly high and elegantly rounded; the shoulders jutted straight out into hard little puffs. Many unlikely, paradoxical tightropes converged into this impossible, rowdy, schizo- phrenic jacket — it was like an Elizabethan motorcycle jacket for the Lady President of Tomorrow.

I felt like it articulated the designer’s heartbreakingly generous interpretation of female power: radical chic that still made traditional sense. It was as if the jacket came with its own brass horn section, to announce your presence in a way that was simultaneously lusty, confident, noisy, and strong — but unquestionably regal. It was an empowering structural muscle that could be used as protective corporate armor, but it was also nonaggressive: stronger for being penetrable. Mighty like a rose.

Ultimately, it revealed something stunningly simple. Like a dream, it installed new doors in an old room, and opened them, revealing a shockingly bright, open, robust new territory for feminine grace. It was refreshing and gladdening to see such courageous invention; an outpour of inspiration with such vivid affection and respect for women, and belief in them.

And it was $2,765 — so there was no chance I’d ever own it, unless I went back with a gun. But I was glad it existed; I was grateful just to see it. After that, luxury boutiques ended up being museums for me. Fashion reviewing sank its hooks into me as a subject, because it was art appreciation, really. Like any mature art form, fashion articulates comments on the world in a distinct way that no other medium can — and in ways I found thrilling and revelatory.

Did you have any other “lightbulb” moments when you started writing fashion?

That Balenciaga jacket was when I first realized, “Oh, it’s art! And it’s saying all these things!” I was able to glean all of this really interesting information from this jacket, because it was saying all of these things. After that, it was everywhere. Then I could go into any store and say “Oh, this is saying so much to me.” That’s why I got so excited about it as a topic.

For the most part, people think about fashion and they think about knowledge. They’re not thinking about…history. It was this idea I had that fashion is a language. When you can see what a designer is trying to evoke by those puffy sleeves or that particular print or cut, because it’s always a callback to something that’s already happened before, it’s invariably about some cultural mood that people are recalling because there’s a sudden need for it. Fashion answers the call to an unspoken zeitgeist need, and then articulates it in clothing.

When you write about fashion, and when you’re articulating what designers are doing, who are writing for?

That’s a curious question. It’s going to sound awful if I answer you honestly…I usually write for an editor. I loved my editor at the New York Times, Anita Leclarc. I’m such a teacher’s pet in a way. I knew what she wanted and I was writing to please and amuse her at a certain point. For this book, I was trying to reach an audience beyond that one editor. I was hoping to grab on to more people. I really felt bad that I got called an elitist because I was working for the Times. For me, that was a ridiculous accusation, because all I was doing was going to stores and going, “Oh, I can’t afford that! How nice for somebody, but not me!” But fashion..it’s not an income-specific art. You can do it no matter how much money you have or don’t have. It’s really more about style. I was trying to reach people who weren’t only the people who could afford the shit on Madison Avenue, but just people who care about their own presentation and trying to encourage that.

When we talk about the lack of really good fashion writing, are we thinking there are people who aren’t being served? Or is it more that there are smart people out there that don’t realize, yet, that there is fashion writing they would be interested in?

This gets into a very deep dish issue for me. I feel like there’s a lot of different areas in the world, like art and music and writing, which used to have some sort of independent arena where you could have art that didn’t necessarily have everything to do with commerce. Ever since the economy collapsed in 2007, everything has everything to do with commerce and only commerce. There are really no independent fields anymore. Capitalism has essentially enveloped everything; everything answers the market in some way.

But there are also these amazing and unique intellectual places of discovery, and they don’t happen to be immediately commercial, so they’re underexplored because it’s not serving anyone’s immediate interests. Like Jacki Lyden from NPR is doing this fantastic podcast called The Seams. And it’s really good, really knowledgeable, really historical. It’s fashion as anthropology. I mean, things like anthropology are sort of falling by the wayside too! These are things that America no longer considers important, like art or music.

That is why it’s very interesting, too, that you said that fashion is a language. When I was writing about the punk exhibition at the Met, my editor told me that she wasn’t interested in a defense of fashion as an art; she told me that it’s about fashion as a language, and how we use it to communicate, which I’ve thought about ever since. So now, if there’s not really a market for anthropology, or art writing, is it because we’re not communicating?

I actually think things got dumbed down! When I finally got sacked from the Times, it was because I was more critical than shopper. They wanted more shopper than critical. If you look at it, most of the cultural critics were canned in the next couple of years, because critical thinking was no longer considered something that people needed. Everything becomes a shopping rag if you’re not having voices of dissent in there. I think it’s really unfortunate what’s happening.

The book actually took so long to write because I took this really strange by-road and got into propaganda, really into the wheels and mechanisms and psychological nitty-gritty of it, advertising and why we want these things, why we have these desires, why these desires look like this. That really became the interesting and horribly spooky thing for me. We are so…brainwashed as a populous. And we don’t even know it. We are so suggestable. These things have been suggested to us for a very long period of time, and by the time they float up to the front of our brains, it looks like our own desires and our own individuality. It’s very manipulated.

That’s why the structure of the book, as well, is interesting; you’re isolating not just the geography of America but the political ideologies of the country, the religious beliefs, and the values and how the clothing aligns.

That surprised the hell out of me. The pitch that I wrote about this book was that I wanted to see if you could see political, economy, regional all the way down to people’s underwear drawers. And what became totally shocking to me was the amount that you could. How much we are influenced by these power structures around us. Wherever you are, there is going to be some pressures on you to conform to something. We’re a very conformist people. But I don’t think people realize the extent to which they have conformed. People conform because they think it’s sort of a default switch for themselves, they kind of roll along with the current, and they don’t realize how much they’ve actually been trained to want the things they want. This is very reified in fashion.

When I was reading the book I was wondering what the difference was between a trend and a social uniform. Like, a trend is here’s kind of pant we’re going to wear for awhile, but a social uniform is like, here’s what you have to wear to belong.

I’m going to say social uniform is something you wear when you want to be innocuous. To blend in. A trend is something that comes around and has a very short shelf life, and you embrace it for the five seconds that it’s cool, and then it’s sort of embarrassing six months later. The whole sort of “Hitler Wears Khaki” phenomenon, when The Gap came along and suddenly everyone was wearing khakis and button-downs and t-shirts…it was inoffensive. Everyone lived through the 1980s and looked at their old yearbooks and was like, “I’m never going to be that embarrassed again! I’m never going to be exciting-looking again!” Everyone just started to want to look classic. Blameless. Which is a very stifling and conformist idea. People should be having a lot more fun.

Blameless is a funny way of putting. It’s interesting to think about what people are avoiding by how they get dressed, that they don’t want to be seen as too much, over-sexualized, calling too much attention to themselves…

I think people avoid things constantly. I say it in the book, too, that there are so many psychological components to what you select in your closet. The items that are there, and the clothes you put on on any given day, are going to compensate in some way for your real or perceived weaknesses. Your psychological weaknesses, or you feel like your butt is too fat, and so you’re going to dress defensively, to sort of camouflage the things you think are your flaws. I think a lot of the time the grotesque amount of energy people spend dressing around what they feel to be their foibles actually makes them way more accentuated. They’re drawing way more attention.

My personal pet peeve is when people want to talk about how they don’t care about clothes at all, they just throw on whatever’s around…

Those people have airtight fashion laws.

Right????

Those guys who are like, “I’m anti-fashion,” they only wear ONE kind of sneaker, they only wear ONE kind of t-shirt, it’s only one cut and one fabric. They’ve got everything locked down to this tiny miserable cage. But it’s totally, totally deliberate. They’re not accidentally wearing anything. Nobody does.

What, in your opinion, can we learn about our own personal style from looking at other people’s personal style?

I think it starts and stop at inspiration. You see people walking down the street, and they look fantastic, and it might not be something that you want to wear, but I think what you’re really enjoying is their enjoyment. It’s making me happy to look at you in it.

Fashion is also contagious. If you see something that would work on you, you’ll adopt it like a piece of slang. It’s contagious like language; it travels in memes like that. For me, personal style is about permission. The permission you have to give yourself to be the unique creature that you are and not worry about all these horrible social inhibitions that have been larded into your brain since birth about how you’re too fat or too short or something. All you need to do to pull off anything, in the world of fashion, is to enjoy wearing it. And to feel good in it. That’s the only rule, really!

Did you find that when you were traveling around America writing this book, you had your personal style influenced in any way?

Oh, I noticed how ridiculous it was in a lot of places. I’ve been wearing all black for so long; I’m a San Francisco death rocker and then I moved to New York. It’s such a lazy fashion choice but I’ve always loved Yohji Yamamoto. I’m not a goth, I’m a death rocker, but I just admire that look. I do one degree of Rick Owens goth as my fashion. That’s where I’m comfortable. I look really stupid in Miami. I look equally ridiculous in Iowa. A French woman, when I was in Miami, was saying “well, if you lived here, your soul would discover color.” I realized, yeah, that’s exactly true. If you steep yourself in any environment long enough you’re going to become that kind of fashion animal.

Do you have constant references for your own personal style?

I get inspiration all the time and I find that it’s way more individual these days. I really admire individual fashion. Of course I love Rick Owens, who doesn’t, but I really enjoy seeing people or hearing about people. Jacki Lyden told me about some teenage boy on the subway who was wearing a 1980s red prom tuxedo as a day look. Which I thought was the greatest thing I’d ever heard! That guy is a star! I want to send him a cookie. I love it when people have things that nobody else has.

That goes back to what you said about watching people enjoy their clothing. It’s nice to see people having a good time with the way they look, and not to use it to cover up their flaws.

It’s really connective! Going around the country, and looking at people, and enjoying their enjoyment of fashion, was an inroad. I would go “Look at that shirt! That’s an amazing shirt!” And they would tell me the whole story about that shirt.

Invariably, when you see a unique item on somebody that they’re really proud of, there’s a great story there. That’s an ingress into that human being. They’re showing you something real about themselves. Which is why I totally resent corporate office wear, and Washington D.C., because it doesn’t tell you anything. There’s no story there. You’re withholding information about yourself by being so boring.

I was also in Washington D.C. recently and I was thinking about how it felt like it was stuck in a different time. When Jackie Kennedy came in, I guess that was considered a big style upheaval, but that was…shift dresses.

That was probably the most radical shift that the presidency has ever seen. Kennedy takes off his hat and Jackie wears a Lily Pullitzer shift dress. And we have not seen its like since! I mean, there was Michelle Obama at the inauguration, when she wore that incredible Narciso Rodriguez.

And she dresses so well, she has such a good sense for designers, but even her silhouettes and the basic ideas of her outfits follow that Jackie Kennedy line. I’m reminded of another editor of mine who once said that when we talk about this idea of timelessness or classic style in fashion, we’re almost always talking about the past.

Safe. We’re talking about safety. When people talk about classic style, they’re saying, “you won’t be embarrassed by this in six months.”

Or no one will challenge you.

You’re not rocking any boats here.

Yeah, but technically timelessness, if we were taking it literally, it should be…futuristic fashion, as well! Something that looks forward and not back.

That is really where I think fashion has become very stagnant in the last thirty years. There are a lot of different reasons for this: there’s no centralized fashion engine coming out of Paris. And if you think about it, most of the great fashion of any decade tends to come out of a subculture. The 1960s are now remembered by the hippies because they were the radical counterculture thing, they were radically anti-establishment. This became that signature boho look. And then in the 1970s we had the disco subculture, in the 1980s we had punk and new wave. These things were genuine subcultures. Punk ideology was very much a political ideology. It was about being disenfranchised as the lower class in the United Kingdom. So when you take a fashion statement, and you neuter it by putting it on a runway or mass-producing it for twelve year olds at K-Mart, what you’re getting is the clothing without the meaning.

I did think a lot about that Valerie Steele quotation in the book, about how all the eras are on top of each other. She said:

There had been no big paradigm shifts in fashion for the last twenty or more years because all the previous decades and their mutually exclusive style signatures were, now, all happening simultaneously.

“This, in a way, is actually a terrific thing for fashion,” Dr. Steele quipped, “because no matter what you look like, there is an era in which you are the magnificent ideal.”

That’s right, there’s no wrong answer to fashion right now, but that also means that there’s no statement. You can actually not make a rebellious statement in fashion now. Like when I was a punk rocker, it was dangerous. People were like, yikes! It hurt people’s eyes to look at because it was radical and new and painful. It meant something. It still had this tang of being really degenerate. It had a little whiff of danger, like Marlon Brando in a leather jacket in The Wild Ones.

When everything is permitted, that means that all of the signifiers are silent. The symbolism of whatever you’re wearing is completely muted; you don’t get a voice in this argument anymore. There’s no way to wear something that tells the man to fuck off or embraces your love of Communism or something. Whatever your statement is.

In the book you said you think the best clothing inspires fear, which is similar to the idea of being afraid of someone who dresses like a punk.

Or just if somebody is extremely well-dressed. Wearing something very plain and demure but it’s very, very elegant, that look is very intimidating. I think that we as a people respond more to fear than we do to love. The death drive is stronger. That’s a thing that advertising knows which most people don’t.

Is that also true of fashion writing? Does the best fashion writing inspire fear?

No. The thing that usually designates good writing or good journalism is a lack of collusion with the thing that it’s writing about. Most of the people who are fashion writers, the people who have jobs, are the people who have been around for a long time and they have a vested stake in the interests of the machinery of the industry of fashion. They’re not really allowed to say anything. They’re not allowed to poke fun at the emperor’s new clothes because they have to keep the industry alive. They’re not paid to be critics. They’re paid to be cheerleaders.

Well, then maybe even if people aren’t being scary in their writing, there’s still a fear as a motivator. They’re afraid of saying anything that could be perceived as negative or not totally in support of the industry.

You have to have both. I’m more known for the negative things I’ve said than the positive, but I think the fact that I can swing so negative enables me to be really effusive about things that I really like. And you know that I mean it! That lends validity to me as a critic, because I’m actually telling the truth. I’m believed because I do tell it the way I see it. People aren’t allowed to do that; it’s a very hard thing to do. It’s a rough thing to do in terms of being a working journalist, because lately no one wants you to do it. I’m not reading a lot about fashion and lipstick and shoes right now. Fashion became more of a holistic problem for me, it became more of an issue. Like art itself instead of branched-out little favorites and things. I just find that most mainstream journalism, of any kind, has been really down in terms of its freedom. In terms of being able to express anything other than consumerist cheerleading.

Do you ever think about the future of fashion?

C: No. [laughs]. But there are some really amazing things going on. I got to wear this Iris van Herpen dress, I was looking at her stuff, the 3D printed design ability that designers have, it’s really enabling us to look at some really wacked out intricate stuff that wasn’t made before. So, sure, there are all kinds of exciting stuff going on. Fashion will always reinvent itself. It has to.