We Need To Talk About The New Elena Ferrante Book

And also all her books, probably! I read the first three when I was on vacation in February; I fucking inhaled them, to put it more accurately. I gave them to my grandmother and my best friend as birthday presents. They’re one week and 56 years apart in age, but I knew they would appreciate them equally. It is, I think, the very best depiction of female friendships I’ve ever read, as well as the sharpest and most painful representation of professional ambition, of destructive desires, of the patterns we let our lives play out both consciously and unconsciously. When I read it, I felt seen. In a good way!! I think!!

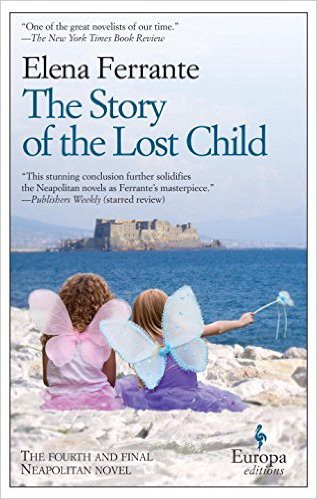

I also — sorry to galley brag — got my hands on the fourth book, The Story Of The Lost Child, but haven’t been able to finish it. I’ve been reading it in controlled doses, trying to balance what I need and what I want from the book, especially knowing that the entire series will be over soon. I mean, I’ll probably just start over and read the entire series again, because I am a compulsive re-reader of the books I love, but it won’t be the same. I was already feeling an anticipatory sense of loss when I read Rachel Cusk’s excellent review of the book for the New York Times. This passage in particular hurt to read, in a good way, I think:

What Ferrante illustrates here is the externalizing of an inner supposition whose contradictions lie deep within the female character in both its realized and unrealized state: The woman who has not proved herself through traditional measures of accomplishment suspects she has brilliance hidden inside her; while the realized woman, the woman who can point to her own successes, is afraid she has none. “She possessed intelligence,” Elena writes of Lila, “and didn’t put it to use but, rather, wasted it, like a great lady for whom all the riches of the world are merely a sign of vulgarity.” Elena’s own use of her talents has been, she increasingly sees, a form of submission too common among women, “and that submission had — through trials, failures, successes — reduced us.”

If you are interested in prolonging the inevitable, you can hide in Dayna Tortorici’s incredible essay on Elena Ferrante in n+1, which also mentions the delayed gratification element of reading a Ferrante book, of killing time by obsessing over her anonymized identity:

Heaping praise is one thing, and praise for Ferrante is not hard to find: she is a master of our time, “the best contemporary novelist you have never heard of,” the “Italian Alice Munro.” But there is no outdoing Ferrante, and the best critical work on her novels has the humility of someone who knows it. “Writing about the Brilliant Friend books has been one of the hardest assignments I’ve ever done,” Jenny Turner wrote for Harper’s, and the admission is a relief. The most one can hope to do in writing about Ferrante is to ignore her. Fixating on her identity is one way to postpone reading — to kill time until the words come.

There’s also her interview in the Paris Review, which has some devastating words of wisdom:

INTERVIEWER

You’ve mentioned disappearance — it’s one of your recurring themes.

FERRANTE

It’s a feeling I know well. I think all women know it. Whenever a part of you emerges that’s not consistent with some feminine ideal, it makes everyone nervous, and you’re supposed to get rid of it in a hurry. Or if you have a combative nature, like Amalia, like Lila, if you refuse to be subjugated, violence enters in. Violence has, at least in Italian, a meaningful language of its own — smash your face, bash your face in. You see? These are expressions that refer to the forced manipulation of identity, to its cancellation. Either you’ll be the way I say, or I’ll change you by beating you till I kill you.

INTERVIEWER

But your characters are sometimes the ones who “cancel” themselves. Amalia may have killed herself. And Lila can’t be found. Why? Are these acts of surrender?

FERRANTE

There are many reasons to disappear. The disappearance of Amalia, of Lila — yes, maybe it’s a surrender. But it’s also, I think, a sign of their irreducibility. I’m not sure. While I’m writing I think I know a lot about my characters, but then I discover I know much less than my readers. The extraordinary thing about the written word is that by nature it can do without your presence and also, in many respects, without your intentions.

The voice is part of your body, it needs your presence. You speak, you have a dialogue, you correct, you give further explanations. Writing, on the other hand, only needs a reader. It doesn’t need you.

When I re-read that passage, I couldn’t decide if it explained my hesitation to finish the series because the books didn’t need me or because I needed the books too much. That’s a good thing, I think.