Scala Coeli

by Carolita Johnson

(“Forgive all our sins and receive us graciously, that we may offer the fruit of our lips.”

In older translations, it’s “calves of our lips,” but Rupert Van Deutz preferred the former for reasons that will become obvious.)

After a month of rain the sun is finally shining through the windows into my Medieval Latin class. We’re reciting and translating the “Scala coeli,”or “Stairway to Heaven” from Latin to French at nine in the morning, a bitter irony. We’re all so groggy that all we aspire to is the coffee machine in the hallway downstairs. “Scala Coeli” is, from what I can make of it, a savagely bullying book of so-called “edifying” stories compiled at some point in the Middle Ages supposedly with a view to inspiring Christian piety and putting aspiring penitents on the first tread of Led Zeppelin’s famous stairway (or maybe that great big escalator I once saw in an old movie). This is how most of the stories go: hapless, well-meaning optimist goes to bed at night, saying to self: “Ah, I’ll become a nun tomorrow,” or “I’ll devote my life to the Lord after this one last delicious wench,” then wakes up dead the next morning.

TOO LATE! These informercials have been brought to you by God, and that one-time offer was valid for a limited time only. If you’d accepted the offer last night, God would’ve forgiven all your sins. Not just some of them, but — yes, unbelievable — ALL of them! But wait! That’s not all! He’d also have thrown in a harp for your afterlife.

(as advertised)

I’ve just finished my American-translating-Medieval-Latin-into-heinous-French act. I like the performances after me to wipe away the memory of mine. Said professor having heaved his usual sigh of relief when I finished up without offering to do one more paragraph, I’m now basking in adrenaline and looking around at my classmates while I come down. And that’s when I notice, while someone else begins their Latin-to-French murmuring, that there’s yet another person sitting among us with a part of their body wrapped in white, sterile gauze.

What is it about Medieval Studies that makes us all begin to resemble mummies? When the History students vacate the classroom to let us in, the difference between our groups is dramatic: they’re all rosy-cheeked and fashion-savvy. The men wear thick, textured scarves jauntily, and the women wear cheery lipstick and flippy skirts, even high heels. They smile. Unlike us.

Is it all the old books embalmed in dry, worn leather that we read? Or the crumbling manuscripts that we handle with white cotton gloves in funereal archive rooms, soaking in through our eyes the harrowing narratives of torture and martyrdom? It’s a fact that at any one moment during this last semester, there has always been at least one person sitting among us with one or more bits of their anatomy wrapped in some kind of medical dressing.

There’s the woman sitting across from me with her foot in a plastic bag. Not to mention the obsessively neat guy with the apparently homemade or vintage (or just old?) cravat, and not an ironic cravat, but a dead serious cravat — who seems to have glued his hair to his head with a thick layer of black shoe wax, and sewn down the flaps of his jacket with heavy thread. He’s not suffering from any apparent injury, but there’s still a sort of if-I-glue-it-all-together-maybe-no-one-will-notice-I’m-falling-to-pieces spirit to his outfit and morbidly self-conscious demeanor. To his right is the Russian girl in sandals with her toes stained yellowish with iodine tincture and covered in some kind of stick-on plastic epidermal shield. And, voila, here we go: the pretty blonde, a musician (a cellist, I think), has three of her fingers swaddled in white gauze today.

Did the Devil appear to her disguised as her cello?

What happens to these medievalists? Is life just one long bloody battle between their bodies and the material world? Do they blindly step out of dusty library archives, right into open manholes? Are their insides constantly aspiring to become outsides?

What worries me mostly is when I begin to wonder how I fit in with them. So far, no bandages. But there may be something going on with my head. For some reason I think I’m feeling the Earth’s inner concentric shells sliding slowly and loosely, faraway and muted, fragile and tremendous … a long, soft murmurous sliding. Could this be the “music of the spheres” the saints describe so ecstatically? If I listen carefully might I hear something beautiful? The saints were visited with such visions, usually after fasting and other bodily privations. Which reminds me: my throat is parched, and I’m currently staring sadly at my empty plastic coffee cup with a stupid, dog-like insistence unbefitting of my level of education.

I woke up much too early and haven’t had enough coffee, is what’s giving me visions. My dog, Carmen, is in heat and wakes me up at sunrise now. The first thing I see every morning is her eyes, turned on me at hi-beam, full of urgency, and welling up with expectation, as if she knows that this time, when we go outside, I’m going to lead her to the strange and intense fulfillment that she only begins to suspect as she searches the sidewalk for traces of it, her teeth chattering softly in her tension. Her eyelashes seem longer. She’s developed a sweet, babyish musk.

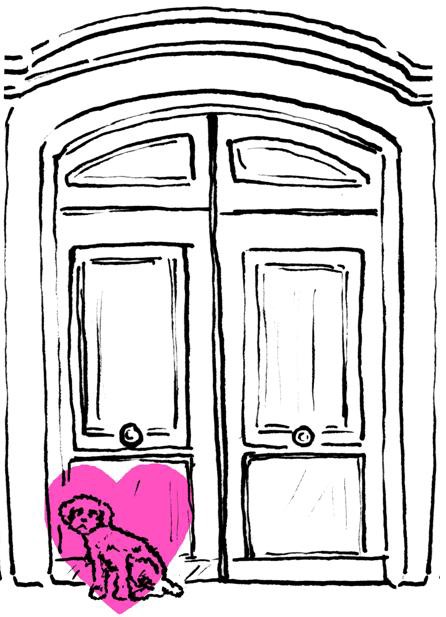

Yesterday, we were pursued for an hour in the Jardin du Luxembourg by a lost and enamored poodle, who I had to escort to the commissariat, and he jumped — not walked — yes, jumped like a kangaroo, jumped as high as my waist, boinged all the way there in an effort to reach Carmen (who I was now carrying in my arms for birth control reasons).

There, a sarcastic gendarme refused to take him in. He tried to palm some mediocre discourse off on me about the “birds and the bees,” implying that I was at fault for walking around with a bitch in heat. Saying outright, not even implying it, that I deserved to have “des difficultés” — as if his lesson in dog-owner civics changed anything for the lost dog!* There was a huge scene in spite of me and my limited (non-academic) French. I probably blustered out an archaic subjunctive usage or two. But I couldn’t help it. I was so worn out and frustrated from running away from dogs all week. The next two weeks will find Carmen leading a cloistered life with me upstairs in our garret, our own personal gynaeceum, members of a harem of two, for my own peace of mind, and hopefully limiting the number of lost dogs in Paris.

Professor Schindler is now recounting an erotic vision of a famous medieval penitent (Rupert von Deutz), and my ears prick up: did I just hear something about an “extraordinary mouth to mouth” and an “erotic trembling”? Wait, Rupert is kissing who? Did I hear that right — he’s kissing Jesus Christ on the cross? And there’s tongue involved? Did I hear the word “breast”? At the front of the room Professor Schindler is asking, “Should we go over this text again?” and looking around. He repeats the question, his eyeglasses flashing in what might be mischief. He’s just put a bustle in our hedgerow, and I can’t believe these sad-sack medievalists aren’t crying out simultaneously with a lusty “OUI!” as I’m tempted to do in a mix of worldly joviality and schoolboy titillation.

In my mind I yell, “Yes, s’il vous plaît, re-read le texte!” and raise a Rabelasian glass of red wine to cheer him on, but my mouth, like the rest of my body, has gone somehow dormant with the rest of the class. I want to rewind that bit about the “tremblement érotique.” Undiscouraged, our professor is looking up at us between sentences, asking, “O.K.?,” (pronounced “Oh-keh? Oh-keh?”), as he elaborates on the “bouche à bouche”and the “baiser extraordinaire.” Maybe he, too, is beginning to wonder if we are all simply embalmed stiff with academic turpitude. Thinking we could all use a baiser extraordinaire right about now.

Oh, re-read the text! It can only help. I start to raise my hand. It’s Spring, and the sun is out. There are reflections of open windows glimmering gently on the ceiling.

*NB: Two weeks later, Carmen was out of heat and back to neutral doghood. On our way back from the park, we saw the enamored poodle in a doorway down the block from our place, now very scruffy, with dead grass clinging to his matted fur, a desperate, haunted look in his eyes. But he didn’t recognize the one he’d given it all up for now, because she didn’t smell the same. He just glanced at us blankly, then turned away to strain his gaze upon the park entrance across the street. Sort of the way I looked at my coffee cup that morning.

Previously: The Devil’s Coach, or A Weekend in Bordeaux.

Carolita Johnson’s cartoons appear in The New Yorker and at Oscarinaland.