Laura Collins Paints The Pop-Culture Matriarchy

Dorinda Medley Pointing at Heather, Laura Collins, 2016.

There was a period in law school when I frequently posed in pictures as Mary Kate Olsen hiding her face from the camera. This was around the time of Amanda Bynes’ mental breakdown. In retrospect, my morbid obsession with women crumbling under the public gaze was likely related to being in law school, where I was told on the daily that my natural way of being was insufficient—that I should speak with more authority, professionalize my demeanor, tame my hair. When Mandy threw that bong out the window, claiming to the probing NYPD officers that it was “just a vase,” I felt strangely liberated.

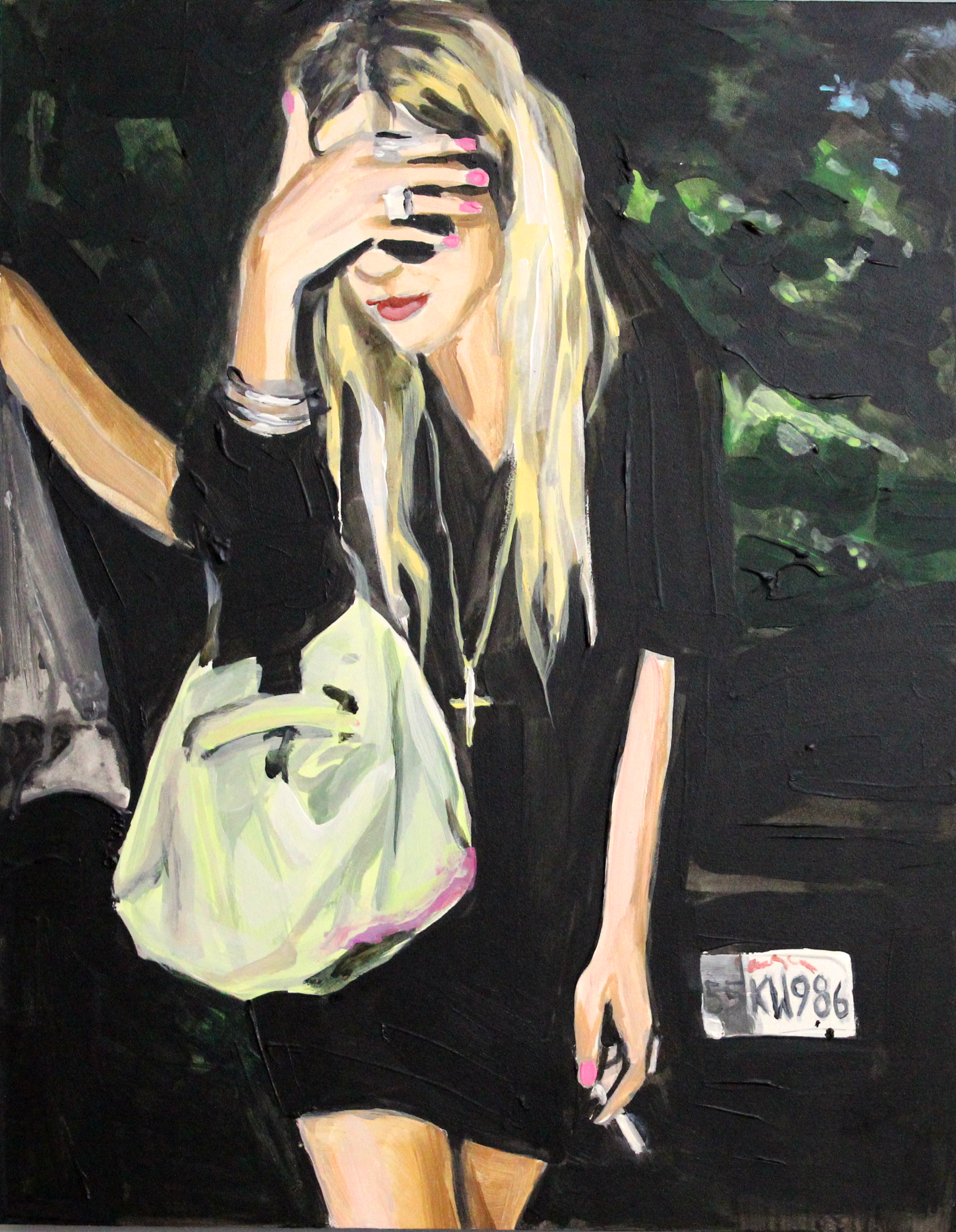

Years later, when I came across Laura Collins’s 2015 series of paintings, Olsen Twins Hiding From Paparazzi, I freaked the fuck out. I devoured her acrylics of Mary Kate covering her face with gargantuan luxury bags, unkempt blonde tresses, and packs of Marlboro Reds. Collins had also recreated Amanda’s iconic post-bong toss courtroom look on acrylic, askew platinum wig captured flawlessly. The Chicago-based artist was painting my most cherished pop culture moments, elevating them to the realm of high art, where I always thought they belonged.

An Olsen Twin Hiding Behind Her Right Hand And Smoking, 2016.

“For centuries, women have been portrayed through paint as reclined nudes and doting mothers,” Collins told me. “We idolize the Mona Lisa and praise her gentle smile, but all it does is reinforce in our society that women should be objectified and keep their mouths shut.” With paintings ranging in subject from Celebrities Crying to Lady Gaga’s Hats, Laura Collins is challenging the status quo.

As someone who has been called “Bravosexual” on more than one occassion, I was thrilled when I got wind of Collins’ most recent series of paintings, Real Housewives Pointing Fingers (currently on display at Brooklyn’s THNK1994 Museum). To counter historical depictions of women as exclusively caregivers or sex objects, Collins’ paintings portray the women of Bravo “aggressively pointing” at one another, in turn embodying “rankism and dominance.” With titles like “Sheree Pointing at Her Party Planner” and “Lisa Rinna Pointing at Her Eyebrow,” the humorous works simultaneously convey an empathy with their subjects, who grapple with the probing public gaze. Collins draws a connection between the Housewives’ pointing outwards and the Olsens hiding their faces from paparazzi. “Both are physical responses to feeling attacked, scrutinized, and being placed in a defensive mode,” she told me.

Collins told me about “a saying that when you point your finger, three more point back at you.” She believes than in addition to seeing the finger points as an act of aggression, “there is a vulnerability and defensiveness at the heart of these gestures”; this dichotomy is what interests her most. This notion conjures many images from my Bravo memory bank: Sheree yanking Kim’s wig on the streets of Atlanta, later claiming she was only trying to “shift it”; Teresa flipping a table due to a book entitled “Cop Without a Badge”; Dorinda inadvertently stabbing herself with a knife while arguing with Bethenny in Mexico. And of course, my personal favorite, an extremely hungover Lu Ann charging Heather in Turks and Caicos, demanding that she “be cool” rather than slut shame her for bringing home a married man the previous night. (The moment inspired Lu Ann’s next single, “Girl Code (Don’t Be So Uncool).”

Lisa Rinna Pointing at Her Eyebrow, 2016.

“Female celebrities,” Collins lamented, “particularly those from reality television, are dismissed as idiotic.” She complained that “investing any interest in their activities is a mark on your own intelligence.” I am likewise irritated that many immediately dismiss reality TV as mindless trash, or worse, a “guilty pleasure.” (i-D opened its review of Collins’ exhibit: “‘Real Housewives’ is the ultimate guilty pleasure. What reality TV show is […] more trashy than one on which you can watch rich American women with melting facelifts pull each other’s hair while binge drinking rosé?”) “Like so many other gendered media texts,” wrote Anne Helen Petersen in Bitch Magazine, celebrity gossip, (an umbrella under which today’s reality stars fall) “causes anxiety […] because it has been labeled, mostly by men, as feminine and frivolous.”

Admittedly, “The Real Housewives” doesn’t have the intellectual heft of, say, a documentary feature on particle science or the ills of the criminal justice system, but it’s no less intelligently crafted than shows viewers readily admit to loving, sans guilt, such as “Westworld” or “Master of None.” In The New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum wrote that while reality TV is an “easily mocked mass artistic medium,” it also provides a “magnetizing mirror for culture.” The mirror shows women who, according to author Sady Doyle, “have succeeded all too well at becoming visible” being “penalized vigilantly and forcefully, and turned into spectacles.” Collins’ paintings depict women coping with this punishment, either by crying, hiding their faces, or deflecting the gaze outwards through aggressive gesture.

Amanda Bynes Wearing A Wig In Court, 2016.

Mindfulness expert Melanie Greenberg, Ph.D. hailed the “The Real Housewives” in Psychology Today for its strong emotional appeal and ability to bond its viewers. Academic provacatrice and “Housewives” superfan Camille Paglia wrote that she adores the franchise for its “frank display of emotion” and the “intricate interrelationships.” (Is there a television relationship more honest and intricate than NeNe and Kims’? Sonja and Ramonas’? Kyle and Kim Richards’?) Collins echoed that the “Housewives” provide “one of the rare cases where you can see women of a certain age forming bonds, going through a plethora of life events, owning their sexuality, dealing with tough relationships, experiencing loss and still forming friendships and enjoying each other.” Her recent series distills these intense emotional exchanges by removing them from their context in order to highlight their nuance and relatability.

Feminist theorist Robyn R. Warhol wrote that books, movies and TV shows that encourage emotions like excitement, desire, or crying have been “systematically devalued by critics.” On the flipside, it can be said that shows like “Real Housewives” are revolutionary in that they present a aspirational version of the world in which women and our stories reign supreme. The Kardashians likewise comprise very public matriarchy, with Kris Jenner and her five daughters at the center, while boyfriends and husbands come and go. The most potent example: Bruce Jenner was not taken seriously by the family until she transitioned to Caitlyn. While Bruce (a world-renowned Olympian) was mostly ignored, or mocked for his “silly,” stereotypically male interests (toy helicopters and golf), Caitlyn was at the forefront of the storylines, gracing magazine covers and participating in public feuds; her transition highlights how the Kardashians prioritize femininity. In spotlighting female stories while ignoring male characters and their interests, reality TV presents an alluring counter-narrative to mainstream society’s tendency to dismiss female concerns. As Collins put it, “Just having that representation is important.”

I asked Collins how she responds when people tell her that her obsession with pop culture is frivolous. “It is not my place to impose my views on how people should spend their money or wear their clothes,” she said. “If you want to wear an entire palette of eyeshadow, get it girl. You probably look great.” When I posited that the appearance-obsessed Housewives and Kardashians may contribute to the objectification of the female figure, Collins immediately provided an alternative: “Valuing one’s own physical appearance is too often viewed as egotistical, and should instead be praised as a worthwhile form of self-care.” Likewise, Paglia praised OC Housewife Tamra Judge’s fanatic dedication to her abs: “[Tamra] is a whirling dervish of physical activity [who] represents the gung-ho athleticism of a new generation of American women.”

An Olsen Twin Hiding Behind a Hermes, 2016.

Subashini Navartnam wrote in her review of Jennifer Egan’s 2001 novel Look at Me, which eerily foreshadowed the the imminent popularity of reality television in that the protagonist agrees to film herself 24/7 for a website called “Ordinary People”:

Indeed, the gaze that is filtered through celebrity culture and spectacle, it turns out, implicates both you and me—the same gaze that people use to worship and judge celebrities in what they wear is the one that people learn to train onto ourselves and their best friends.

It is therefore of crucial importance to interrogate this gaze, and to think critically about how and why the public reacts to famous women. Collins’ recent paintings encourage us to think twice before dismissing the reality TV genre and the alpha women who grace its screens. At the show’s opening, for example, viewers took turns sitting in the “Tamra Judgment Zone, described as “a place to reflect while [OC housewife] Tamra’s most famous quotes ‘You will never see my face again,’ ‘that’s my opinion,’ and ‘here’s your f*cking letter bitch,’ hover above your head.” Collins hopes the show “makes my viewers reconsider their role as spectators both inside and outside of the gallery.”

“Real Housewives Pointing Fingers” is on view at THNK1994 Museum from October 7th–November 12th.